In 1970, a young man arrived at Gandhiji’s ashram in Sevagram. A year later, he joined a medical college, not as a student but as an artist.

Although he left the college after twenty-five years, he left behind footprints in the black cotton soil of Sevagram.

The medical institution was 𝗠𝗚𝗜𝗠𝗦, and the young man was Sitaram Vooturi.

As fate would have it, he began an unexpected journey that intertwined his passion for art with the mission of the college.

Artists are often known for their whims, fancies, and unique quirks. Their tempers and moods can swing dramatically, reflecting the highs and lows of their creative journeys.

Sitaram was no exception; his unpredictability was part of what defined him as a true artist.

This morning, while I was taking ward rounds in the hospital, I had the chance to meet Sitaram. Recognizing the importance of his story, I took some time to listen. As he spoke, I took notes, eager to share his insights.

𝗘𝗮𝗿𝗹𝘆 𝗟𝗶𝗳𝗲 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗪𝗮𝗻𝗱𝗲𝗿𝗹𝘂𝘀𝘁

Born in Jagtial on 7 March 1949, then a small town in Andhra Pradesh, Sitaram grew up in a humble family. His father, Satyanarayana, owned a business and cinema halls, while his mother, Amrita, was a homemaker.

Tragedy struck in 1965 when his father passed away, just before Sitaram was to take his 12th-grade exams. He could have easily gotten into three engineering colleges in the state, but he chose a different path. Instead, he enrolled in a teacher training course, where he discovered his interest in the Wardha Education Plan created by Mahatma Gandhi in 1937.

After finishing his training in 1968, Sitaram set out on a two-year journey across India. He simply wanted to discover the country and its rich culture.

He had no agenda, no plans, and no itinerary. Each day was a new adventure, every night on the train taught him something, and each town he visited added to his knowledge.

His travels brought him to Sevagram on March 7, 1970, his 21st birthday. With no connections or plans, Sitaram arrived at Gandhiji’s Ashram, unsure of what lay ahead but searching for a sense of purpose.

𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗙𝗼𝗿𝘁𝘂𝗶𝘁𝗼𝘂𝘀 𝗘𝗻𝘁𝗿𝗮𝗻𝗰𝗲 𝗶𝗻𝘁𝗼 𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗠𝗚𝗜𝗠𝗦

Sitaram met Mr. Chiman Lal Bhai, who welcomed the young man, penniless but full of hope, and offered him a place to stay at Rustam Bhavan. He advised Sitaram to speak with Prabhakarji, the Ashram secretary. Prabhakarji saw potential in him, despite his confusion, and recognized his passion. He offered Sitaram a managerial position at an Ashram in Shivrampalli near Hyderabad. However, Sitaram’s heart was set on staying in Sevagram. In the end, Prabhakarji gave in, and Sitaram found his home and purpose in Gandhi’s Ashram at Sevagram.

The year was 1970. MGIMS had just opened its doors, and the first batch of medical students had been admitted. Sitaram, still an unpaid Ashram inmate, spent his time making drawings at the Ashram. Yet, he wondered if he could find a way to earn a living at the medical college.

He had no certificates, no formal degrees—only a strong desire to prove himself.

Manimala Chaudhari, the secretary of the Kasturba Health Society, and Dr. I.D. Singh, the principal of MGIMS, were regulars at Gandhiji’s Ashram. Every evening, they would sit cross-legged under the large peepal tree for the evening prayers. Sitaram often ran into them during these peaceful gatherings, slowly becoming a familiar face in their midst.

In the summer of 1970, Sitaram formally met Dr. I.D. Singh in his modest, bare-bones office—just two or three small rooms with minimal furniture, a far cry from the more elaborate principal’s office of today. The entire administrative staff, consisting of Mr. Deshmukh and Mr. Khare, also shared this humble space.

Sitaram, though a humble villager without formal qualifications, carried an intense passion for art and a natural talent for drawing. Dr. Singh asked Gajanan Ambulkar, the young artist in Anatomy, to test Sitaram’s drawing skills. Gajanan handed him 𝘎𝘳𝘢𝘺’𝘴 𝘈𝘯𝘢𝘵𝘰𝘮𝘺 and asked him to replicate the detailed illustrations.

One look at Sitaram’s sketches, and Gajanan nodded in approval.

Sitaram finally made his way into MGIMS. He impressed enough to land a job in the Pathology department, earning just ₹60 a month. But that was just the start. For the next 25 years, he stayed rooted in Pathology, carving out his place, never once looking back.

𝗔𝗿𝘁𝗶𝘀𝘁𝗶𝗰 𝗖𝗼𝗻𝘁𝗿𝗶𝗯𝘂𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻𝘀 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗖𝗲𝗹𝗲𝗯𝗿𝗮𝘁𝗲𝗱 𝗘𝘅𝗵𝗶𝗯𝗶𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻𝘀

Instead of sticking to just making simple charts and drawings for the museums of the second MBBS departments—Pathology, Microbiology, Pharmacology, and Forensic Medicine—Sitaram went beyond. He became involved in exhibitions that showcased not only his own art but also the creative talents of the medical students.

Every winter, the batches of 1969, 1970, and 1971 proudly displayed their artistic talents at an exhibition in the staff club on campus. One of Sitaram’s early standout pieces was a semi-painting inspired by the tragic 1971 India-Pakistan War. Positioned at the entrance, it captivated the audience and became the highlight of the event. This stunning artwork cemented Sitaram’s reputation as a gifted artist within the college community.

𝗧𝗿𝗮𝗻𝘀𝗶𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻 𝘁𝗼 𝗘𝘃𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗠𝗮𝗻𝗮𝗴𝗲𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁

As the medical college grew in stature, so did Sitaram’s role. He had acquired a new skill—planning, organizing, and executing conferences. His attention to detail and organizational talent naturally led him into event management. Sitaram became the go-to person for planning conferences, ensuring that everything—from seating arrangements to banners and decorations—was flawlessly executed.

Sitaram’s style mirrored the values of MGIMS—clear, simple, and effective. He believed less was more. With minimalism, he brought out his creativity in every event, making a lasting impression without excess.

In October 1973, MGIMS hosted the silver jubilee conference for leprosy workers, drawing 600 delegates from 60 countries. Sitaram took charge of every detail, from logistics to execution. His efforts ensured the event ran seamlessly, reflecting Gandhi’s values of compassion and service.

His ability to blend different parts into a unified whole helped raise the college’s reputation both nationally and internationally.

𝗠𝗮𝘀𝘁𝗲𝗿𝘆 𝗶𝗻 𝗦𝗹𝗶𝗱𝗲 𝗠𝗮𝗸𝗶𝗻𝗴 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗠𝗲𝗻𝘁𝗼𝗿𝘀𝗵𝗶𝗽

Sitaram, always restless and eager to learn, set his sights on a new field—making 35 mm slides for presentations at seminars and conferences. From the 1970s to the early 1990s, long before PowerPoint, he became a skilled slide maker.

Researchers relied on his work to present their findings, using 35 mm slides with slide projectors at conferences. His creativity now had a new medium.

Sitaram mastered the art of slide-making with precision. He captured images with a 35 mm camera, developed the film, and projected the negatives onto slide film. After carefully framing and labeling each slide, he created engaging presentations that left a lasting impression.

He taught residents and young faculty the essential rules for making effective slides. “Use large, readable fonts so everyone can see,” he advised, “and keep text to key points to help focus.” He stressed the need for “high-quality images to enhance understanding.” Sitaram emphasized simple design, saying, “Avoid clutter to keep the audience’s attention,” and highlighted the importance of a clear flow, reminding them that “each slide should connect logically to the next.”

He encouraged direct engagement with the audience, teaching that slides should support the presentation, not be read verbatim.

This was during the 1980s and early 1990s, long before the internet existed, and there were no online resources to learn how to create effective PowerPoint slides.

Sitaram was truly ahead of his time.

Besides making slides, Sitaram worked closely with residents and young faculty, helping them practice their presentations. His support built their confidence and skills, leading 19 postgraduate students to win gold medals and best paper awards at various conferences.

He enhanced the learning atmosphere at MGIMS, turning shy speakers into confident presenters and underscoring the value of clear communication in medicine. His legacy of mentorship continues to inspire alumni, reminding them of the power of storytelling in their medical practice.

𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗗𝗲𝗽𝗮𝗿𝘁𝘂𝗿𝗲 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗟𝗲𝗴𝗮𝗰𝘆

In 1995, Sitaram’s journey at MGIMS concluded as abruptly as it had started. In a surprising twist, he chose to leave Sevagram. I didn’t ask him why, and he didn’t share the reason either.

He served for 25 years and could have stayed for another 12 before his formal retirement, but true to his artistic nature, he chose not to. What he left behind on the MGIMS canvas was a legacy of rich work and a unique style.

What do you remember about your time here?” I asked Sitaram. His eyes welled up with emotion as he began softly, “MGIMS was more than just a workplace; it was a family. No matter your role, everyone loved and supported one another. We weren’t driven by money; it was our shared passion to elevate this institute to world-class standards.

𝗔 𝗧𝗶𝗺𝗲𝗹𝗲𝘀𝘀 𝗖𝗼𝗻𝗻𝗲𝗰𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻 𝘁𝗼 𝗠𝗚𝗜𝗠𝗦

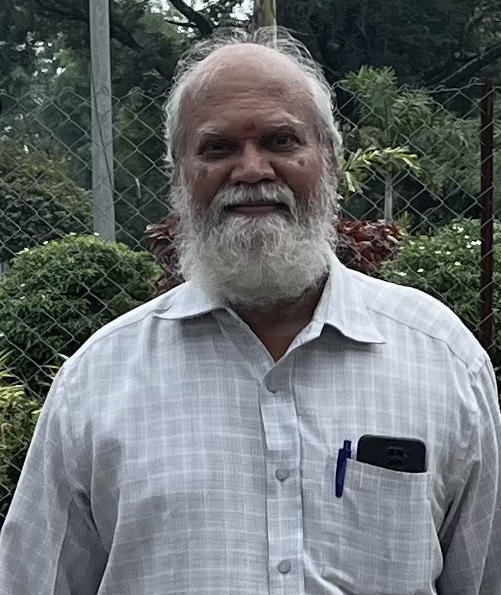

Sitaram, now 75, left MGIMS 30 years ago, but his bond with the institute remains unbroken. His deep connection still draws him back 3 to 4 times a year, where he meets the people he once worked with.

Though the younger generation may not recognize this tall, slender man with a long white beard, who is aging gracefully, his eyes shine with a passion that reflects his profound love and respect for MGIMS.

“I will never forget Gajanan Ambulkar,” he continued, his voice thick with gratitude. “He knew how to manage me—intense, passionate, and short-tempered as I was. He was not just a mentor but a guru, who had the gift of calming my fiery heart while bringing out the best in me.”

As I listened to Sitaram, it was clear that his journey at MGIMS was about more than art; it was about the deep connections he made. His passion for teaching and creativity continued to inspire those around him.

Sitaram’s legacy lives on, not in titles, but in the lives he touched and the community he built.