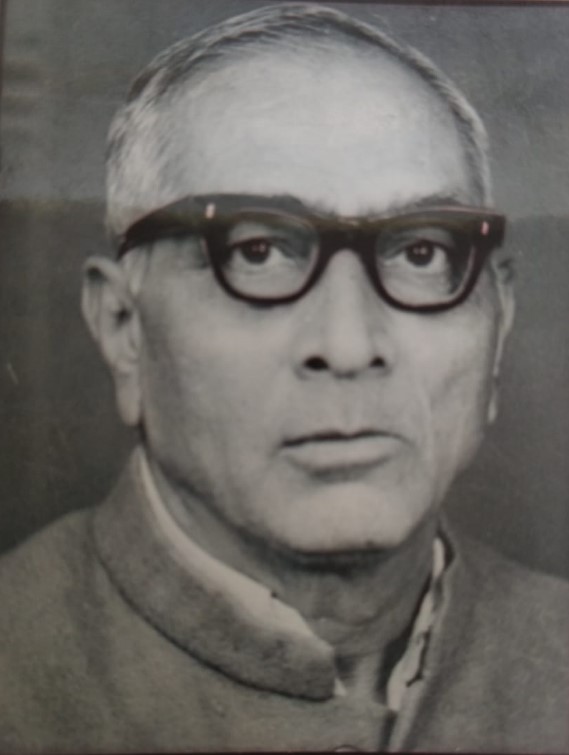

Nalinbhai Mehta’s khadi rustled as he moved, a man of quiet authority. His square face, broad jaw, and deep-set eyes carried the weight of responsibility. A ledger lay open before him. He scanned it, catching every detail. His voice, steady and deliberate, commanded attention.

Numbers spoke to him. He read them like a seasoned navigator reads the stars—unfaltering, precise. Finances were not just figures on paper; they were the pulse of the institution. Without them, dreams remained dreams. With them, MGIMS took shape.

Before the college even existed, Nalinbhai safeguarded its financial future. Rupees, however scarce, never went to waste. Government grants, donations, hospital revenues—he stretched every paisa, making it count. Year after year, his balance sheets left auditors nodding in approval. Clarity, precision, and trust were his currency.

Nalinbhai Mehta had a rare gift—he understood money, not just as numbers but as the lifeblood of an institution. His instincts for finance kept the organization afloat long before MGIMS was even a blueprint.

He made every rupee work. Government grants, donations, hospital revenues—nothing slipped through the cracks. He stretched each paisa until it yielded its full worth. Year after year, his balance sheets told a story of discipline and precision, so immaculate that even the sharpest auditors found no room for doubt.

Born in Karachi on January 17, 1917, Nalinbhai Mehta’s early years were a stark contrast of privilege and hardship. The devastating loss of his mother at three and his father at seven left, losses that time would not fully heal. Adding to their hardship, his father, a once-prosperous merchant trading fine crockery in Karachi and Mumbai, faced financial ruin in 1922 when a ship carrying his entire inventory sank. This catastrophe forced the family into bankruptcy, uprooting them from Karachi to start anew in a small town in Gujarat.

Orphaned young, Nalinbhai Mehta found shelter in Halvad, a small village in Gujarat’s Morbi district. His stepmother and uncle raised him, but his restless spirit refused to be confined. Schooling in Surendranagar came with its own struggles—money was scarce, and college was a distant dream. To make ends meet, he worked while studying, apprenticing under photographer J.J. Mehta.

Then came the call of freedom. At nineteen, he stood shoulder to shoulder with India’s independence fighters. His convictions cost him four months in a British prison—a steep price for a teenager, but one he never regretted.

Even in turmoil, his sharp mind found purpose. He honed his accounting skills, an ability that would shape his future. Perhaps it was destiny. As an Audichya Sahastra Brahmin, he carried a surname that, in Gujarat, stood for financial expertise. “Mehta” meant banker, accountant, trustee. He lived up to the name, making numbers work not just for himself, but for an entire institution

In 1936, Sarvodaya worker Babalbhai Mehta urged 19-year-old Nalin to visit Sevagram and meet Gandhi—a meeting that changed his life. Gandhi sent him to the Khadi Gramodyog Vidyalaya to work with economist and freedom fighter J.C. Kumarappa. Under Gandhi’s guidance, Nalinbhai embraced frugality and dedication to work—principles he upheld throughout his life.

Kumarappa’s vision of self-sufficient villages—built on local resources and diverse skills—left a deep mark on Nalinbhai. He didn’t just admire the philosophy; he lived it. Thrift became second nature. He shaved his head to save on haircuts, wore simple clothes to conserve fabric, and treated every paisa with care.

But more than austerity, Kumarappa taught him the art of financial discipline. Precision in record-keeping, the rigor of balancing accounts, the wisdom of making money work—these lessons shaped Nalinbhai’s future. They weren’t just theories; they became the bedrock of his success.

Kumarappa’s financial wisdom didn’t just influence Nalinbhai—it set his course. What began as admiration grew into a deep bond between mentor and disciple.

Life moved forward. Nalinbhai married Madhu Lata, a woman from his home district. Kumarappa, who cherished her like a daughter, marked the occasion with a rare gesture. He gifted her a gold armlet—a token of his affection. To Nalinbhai, he gave two prized possessions: an Omega watch and a Zeiss Ikon camera. More than gifts, they were symbols of trust, a reminder that he had found not just a mentor, but family.

Madhu Lata battled rheumatic heart disease for nearly thirty years, her heart weakened by a blocked valve. On May 19, 1987, in Ahmedabad, the fight ended.

Through the years of illness and resilience, she and Nalinbhai built a family. They had three children—sons Rajiv Lochan and Bharat Bhushan, and a daughter, Vrinda. Her passing left a void, but the family she nurtured remained her lasting legacy.

In 1964, Sushila Nayar, then India’s Health Minister, set out on an ambitious mission—building a rural medical school and hospital. Lal Bahadur Shastri had planted the idea, urging her to train doctors who would serve the villages.

As India approached Mahatma Gandhi’s centenary in 1969, the vision gained momentum. The Gandhi Smarak Nidhi stepped in, launching a nationwide fundraising campaign to turn the dream into reality.

Vaikunthbhai Mehta, a respected Gandhian and cooperative leader, took charge of the fundraising effort. But fate had other plans—he passed away before he could see it through.

The responsibility fell to Nalinbhai Mehta. He stepped in without hesitation, managing the collected funds with his characteristic precision. Splitting his time between Delhi and Sevagram, he immersed himself in the project, his bond with it growing stronger with each passing day.

In September 1964, the Kasturba Health Society took shape. It began with a handful of committed individuals from Sevagram—Dr. Sushila Nayar, then Union Health Minister, matron Manimala Chaudhury, Dr. Anant Ranade from Kasturba Hospital, and Nalinbhai Mehta. Others joined from across the country: Shri Laxmidas Mangaldas Shrikant from the Gandhi Smarak Nidhi in Delhi, Shri Shriman Narayan from the Planning Commission, and Shri Raghunath Shridhar Dhotre from Wardha.

To steer the society, Dr. Sushila Nayar appointed trustees. Kamalnayan Bajaj, a Member of Parliament, took on the role alongside Nalinbhai Mehta and herself. Their leadership would lay the groundwork for something extraordinary—a healthcare institution that would redefine medical education in rural India.

In 1969, as the Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences (MGIMS) prepared to open its doors, the Gandhi Smarak Nidhi provided a one-time grant of one million rupees. But there was a condition—no more funds in the future. MGIMS had to stand on its own. Nalinbhai Mehta took on multiple roles—finance advisor, member-in-charge, and trustee—playing a crucial role in shaping the institute’s early years.

In 1965, four years before MGIMS admitted its first batch of sixty students, a 19-year-old P.L. Tapdiya met Dr. Sushila Nayar for the first time. Then an apprentice studying to be a chartered accountant, he had no idea this meeting would define his career and bind him to the Kasturba Health Society for six decades. That day, he never imagined he, too, would one day become its president, walking the same path as Dr. Sushila Nayar.

The accounts office was a study in austerity—two cramped rooms under a sloping kavelu roof, their stone floors cool against the sweltering Vidarbha heat. A flickering tubelight cast a dim glow over the space, where wooden shelves sagged under the weight of thick ledgers. A noisy table fan whirred in the corner, pushing warm air over stacks of yellowing files. The room smelled of ink, old paper, and the occasional whiff of kerosene from a nearby lantern.

In one room, Manimala Chaudhary, the formidable secretary of the Kasturba Health Society, sat at her desk, her upright posture and clipped handwriting reflecting the discipline she demanded. She was the second most important person in the organisation, and every financial decision passed under her sharp gaze.

In the adjoining room, three men shared a single, battered wooden desk, its surface cluttered with ink pots, ruled registers, and frayed cloth pouches filled with currency notes. Dadarao Shingare, a wiry man with deep-set eyes, sat closest to the cash box, his fingers instinctively flicking through worn banknotes, counting and recounting with practiced precision. Kanakdas, the youngest of the three, perched on a wooden stool, scribbling entries in neat columns, his forehead creased in concentration. Bhimrao Pradhan, his spectacles balanced precariously on his nose, muttered calculations under his breath, his calloused fingers flipping through budget sheets.

Tapdiya stood among them, supervising, suggesting, occasionally dipping his pen into the inkwell to jot down figures in the thick, leather-bound ledgers. Together, they managed the finances of a growing institution, their workspace more an assembly of determined minds than of formal training.

None of them had studied finance.

Dadarao Shingare had left school after the sixth grade. Yet, he had handled the cash flow of the old 50-bed Kasturba Hospital long before government grants arrived, keeping meticulous records when every rupee mattered. The local Wardha Zilla Parishad filled the funding gaps with a deficit grant, and it was Shingare who ensured not a single paisa was unaccounted for.

Kanakdas’s story was even more remarkable. In the mid-sixties, he arrived in Wardha from Kerala, nearly illiterate and orphaned in adolescence. Stepping off the train with little more than hunger in his belly, he walked to Sevagram in search of food and shelter. Manimala Chaudhary noticed the frail boy lingering near the kitchen and took him in. She found him a job—ringing the hourly chime in the ashram.

He knew no Hindi, no English. But he watched. He listened. He sat beside Dadarao, fetching papers, filing documents, running errands. At night, he studied by the light of a kerosene lamp. He passed his matriculation, then pored over the General Financial Rules, memorizing them like scripture. By 1975, the bell boy had become the chief accountant.

Bhimrao Pradhan had studied up to the tenth grade in Yavatmal. He began his career as a laboratory attendant, then spent a few months assisting a technician before shifting to accounts. There, he learned to handle cash, prepare budgets, and balance sheets—first hesitantly, then with the steady confidence of a man who knew his numbers.

None of them—Shingare, Kanakdas, or Pradhan—had studied commerce. None had ever worked under an accountant. And yet, in that dimly lit room, armed with ink-stained fingers and an unshakable resolve, they managed an annual budget of ₹1,00,000.

“Am I to blame if I entrust sensitive jobs to men who may not be very bright but on whom I can rely?” Dr. Sushila Nayar once said, defending the employees who managed key sections of the hospital.

For five years, Nalinbhai shuttled between Delhi and Sevagram, dividing his time between managing funds and overseeing the fledgling institution. When in Sevagram, he lived simply—often sleeping on the floor, riding a bicycle to inspect the Society’s agricultural land.

In 1970, he moved permanently. By then, he was already a founding member of the Kasturba Health Society and one of its trustees. He took charge of the accounts office, ensuring every rupee was accounted for.

His workday began at 4 a.m. “Son,” he chuckled, “4 a.m.—that was my happy hour! Three quiet hours, just me and the numbers. No phone calls, no meetings, no interruptions. I could balance the books, track every paisa, and get things in order. Once the office opened, it was chaos. I had to be ready.”

Nalinbhai didn’t just oversee the institution’s finances; he controlled them with an iron grip. His desk was not merely a workstation—it was a stronghold protecting every rupee. A single misplaced digit in a ledger would prompt a sharp glance, while an unclear expense would summon a booming interrogation.

Frugality wasn’t just a principle for him; it was a way of life. His own austere lifestyle—simple clothes, modest meals, and an unwavering commitment to accountability—was a silent yet powerful statement. There were no hidden dealings, no murky corners in his books. Transparency was not just a policy; it was his creed.

He convinced Dr. Sushila Nayar that the three pivotal figures—herself, Manimala Chaudhary, and Nalinbhai—would accept only a nominal honorarium of ₹500 per month. Over the years, this amount increased in small increments of ₹500, reaching ₹2000 by the time a stroke in 1991 left him paralyzed.

He and Mr. Tapdiya both understood that financial integrity was paramount. Mr. Tapdiya’s presence provided an invaluable extra layer of scrutiny—if a rare error ever slipped past Nalinbhai’s watchful eye, Mr. Tapdiya was there to catch and correct it. Few institutions are fortunate enough to have such individuals—masters of numbers who recognize that sound financial management is the backbone of any organization, without which everything would collapse.

It was no surprise that Nalinbhai enjoyed Dr. Sushila Nayar’s complete trust and autonomy. In 1991, when she visited him at home after his stroke, tears filled her eyes. “Nalinbhai,” she said, “I had no idea how meticulously you kept the accounts. Where will I find someone like you?”

He shared a bond like family with Sarla Parekh. Their work wasn’t just about asking for money—it was about building trust. Every handshake, every conversation, meant something.

He knew a small gift from a shopkeeper mattered as much as a big donation from a company. Every rupee counted. He treated each donor with the same respect. People believed in him because he believed in the mission. That’s why they gave, not just money, but their faith.

His work didn’t end when office hours did. His simple home wasn’t just a place to sleep—it mirrored his values. Every rupee he saved wasn’t just a number in a ledger. It kept the institution running. He knew that every paisa mattered.

Over the years, he built strong ties with Sushila Nayar, Manimala Chaudhary, Parmanand Tapdiya, and Sarla Parekh—the pillars of the organization. In 1982, he and Shri Tapdiya arranged a lunch meeting between Sushila Nayar and Dhirubhai Mehta, bringing Dhirubhai into the fold. After Annasaheb Sastrabuddhe’s passing, Dhirubhai stepped in as Vice President. He became Sushila Nayar’s trusted ally and, after her death, led the institute for 24 years. Tapdiya was to take over from him in 2024.

In 1991, while in Gujarat, Nalinbhai suffered a stroke. It took his strong voice and left him unable to move his right arm and leg. He spent nearly a decade confined to his home in Ramdas Colony. He never recovered. It was a difficult time, not just for him but also for his daughter-in-law, Lata.

Lata cared for him with unwavering devotion. She was more than a daughter-in-law—she was like a daughter. Through every struggle, she stood by him, tending to his needs with quiet strength and deep compassion. From the smallest tasks to the hardest moments, she gave him comfort, support, and love.

On June 17, 2000, he passed away at home, surrounded by Lata, Bharat, and his loved ones. Sevagram lost one of its own. Six months later, Dr. Sushila Nayar followed. These two pillars had witnessed MGIMS’s entire journey—from its birth to its growth, through struggles and triumphs. How many today remember their legacy?