Medical case records carry a story. They describe the journey of patients from the admission to the discharge. They tell us, chronologically, why were the patients admitted, how were they diagnosed, why doctors couldn’t fix their problems, how were they managed, what complications did they develop, what made them stay long and finally how did they fare.

Most case papers in our hospital do not tell this story.

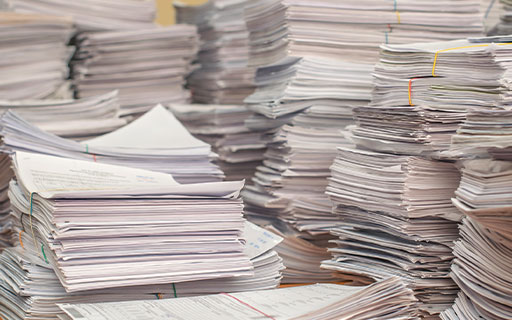

For the last few weeks, I kept gazing at the piles of papers heaped in stacks in the hospital wards. I sampled a few papers and began browsing through them. Many papers were completely bare. No trace of doctor’s trademark illegible hand-written scribbles. Or carried histories so short that I became envious of doctors who could accurately diagnose their patient’s misery on the basis of three short sentences. Many patients couldn’t make it to page 3- on their case records. Vital signs made regular appearances on the papers- patients seemed to share the same numbers- their pulse, respiratory rate and BP was remarkably similar- day after day. And although the cover page of the case record at times indicated a terrible disease, the inner sheets carried little or no text to explain the disease. If these case papers were anything to go by, patients with perforation peritonitis came, had their bowel stitched and went home alive- not because of but spite of their doctors.

Eighteen thousand. The number of papers scattered all over the hospital in September. Papers choking ward-in-charge’s cupboards, suffocating themselves in the drawers and gasping in the doctor’s lockers. Probably white once upon a time, the papers had turned yellow now and they lay everywhere- behind coolers, atop the refrigerators, over the table tops, and under the resident’s hostel mattresses.

I coaxed, cajoled, gave a pep talk, wrinkled my forehead, taxed my vocal chords, reasoned with nurses and appealed to the residents to finish the pending job- completing the papers. I wanted the papers to go to the place they belonged to- the Medical Record department.

Everybody responded to my request- given a choice they would not have but did they have an option? I knew that nobody liked this job. Who wants to fill sheets of papers with non-existent physical signs and fictitious histories for patients who had left the hospital months and years ago? “What do we write”, asked interns, “on case records of babies who were delivered, stayed for a while and left the hospital with their mothers when we were studying Pathology?” “How do we compile injury reports for patients we never saw or managed”, asked the surgery residents. Honestly, I had no answer. I also wonder if such notes are even worth the price of paper that they are written on.

And so, over a four-week period, these papers finally managed to reach their repository- the MRD. Having travelled a kilometer- from the wards to the MRD- another cycle awaits them. MRD technicians would use MRD numbers to sort them, bunch them up and put the pile of papers on the steel racks. Only a handful of papers might be recalled- in the courts – or ordered by the guides who still subscribe to the validity of thesis based on incomplete chart reviews. The rest are destined to die an unsung death after 5 years- they will be shredded and recycled.

And the story will continue.