Beginning May 2020, we admitted hundreds of patients with COVID. But in the middle of last month, something changed. Patients arrived with problems we had not yet seen in the pandemic: people were not only breathless and feverish but also had pain and pressure behind their cheekbones and around their eyes. Some lost their vision.

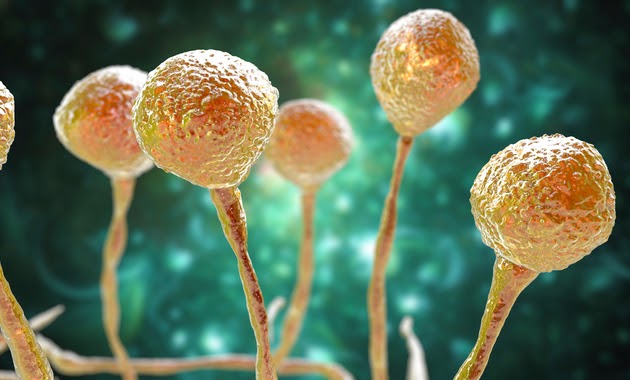

We soon realised that this was Mucormycosis—infection with a rare group of fungi called mucormycetes. Their cases were some of the earliest indications of a wave of illness that is now swamping India—an epidemic within the pandemic. There was no fungus in the first wave of COVID, but in the second wave the black fungus is painting the country red.

Mucormycosis— “black fungus,” colloquially—can infest the sinuses and bones of the face and invade the brain or cause patients to lose an eye. When it goes untreated—and treatment is prolonged and difficult—mucormycosis can kill up to half of those who contract it.

There have been almost 12,000 cases of the infection in India in recent months, with most of them occurring in Maharashtra and Gujarat.

Could high sugar—and steroid use— account for this epidemic within a pandemic? High sugar levels provide a perfect milieu in which the black fungus can throw, grow and destroy the victim. Even in rural areas, every eighth adult aged 30 and beyond is diabetic. Most have suboptimal control of sugar. When these patients test COVID-positive, they often are prescribed high-dose steroids, often in the first week. Steroids save lives, but they simultaneously make a patient more vulnerable to attack by whatever bacteria or fungi are already in their body or hanging around their environment.

Even antifungal drugs are in short supply and they may be unaffordable for most. There are relatively few categories of antifungals, and while some of them have been available for decades, newer versions that are less toxic to patients are expensive and scarce. For the preferred drug, one-day therapy costs 30,000 rupees (about $410), a catastrophic health expenditure for 99 percent of Indians. The therapy often lasts for weeks and requires an intravenous infusion, admission to the hospital and close monitoring of the kidney function.

Can we predict when shall this end? Could, greater awareness of patients’ vulnerability might allow physicians in India to recognize cases earlier? Could more rational use of steroids in Covid— only in hospitalised hypoxic patients—help us in preventing this deadly fungus hitting the eyes and invading the lungs?

The earlier we learn lessons, and respect science, the better.