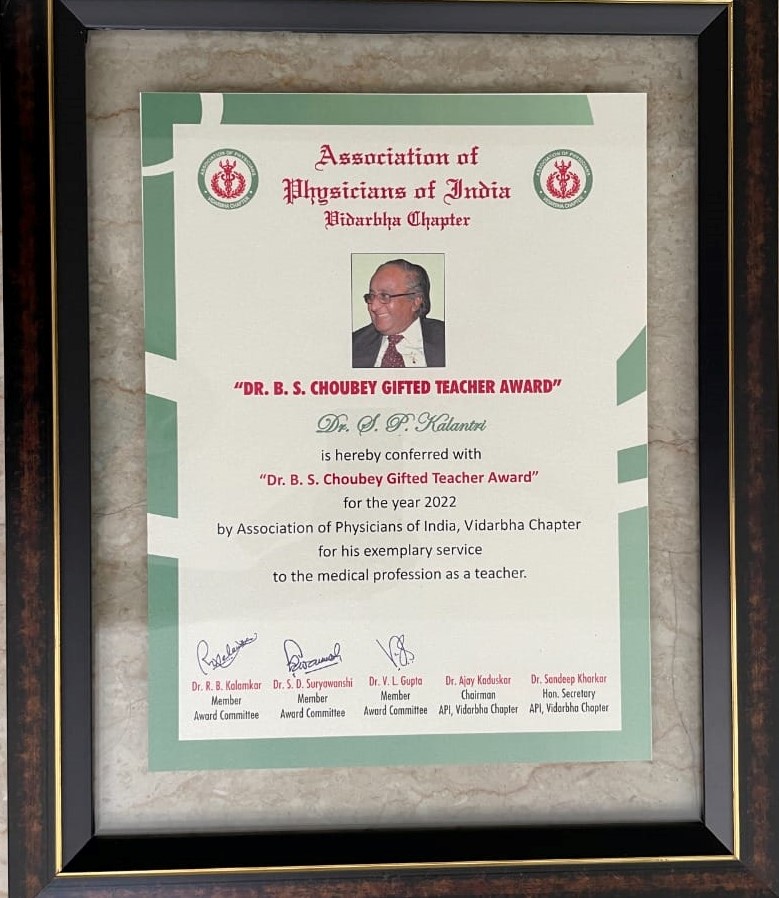

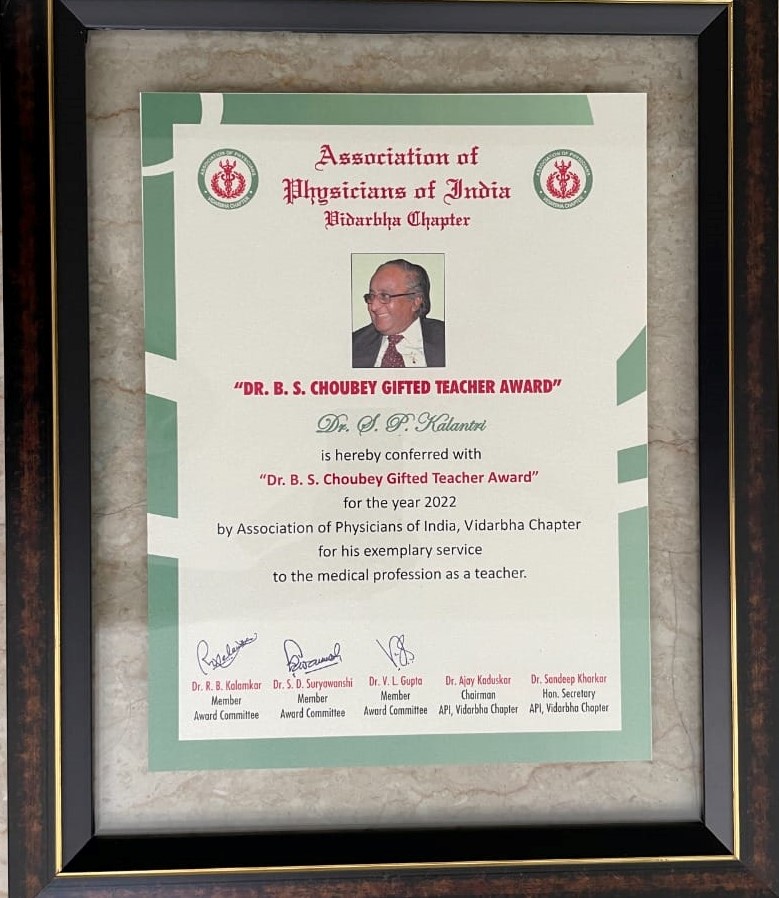

On 17 September 2022, I was conferred Gifted teacher Award, named after my teacher Dr BS Chaubey. I was interviewed on the occasion of this award.

Sir, we know you as a teacher but we would like to know about your childhood.

Born on August 15 —I was the youngest of six siblings. My mother was a homemaker and father, a manager in a local cotton and ginning factory. I went to three schools: Nagar Parishad primary school (Hindi medium), Cradock High school (Marathi medium) and Swavalambi Vidyalaya (quasi English medium). In 1972, I got enrolled into a local science college; a year later I was admitted to the Government Medical College Nagpur. Early education in Hindi and Marathi shaped my love for books, a passion that has only grown with the passage of time.

I did not come from a family of doctors. It was partly maths phobia and probably a genetic mutation that explains why I landed in GMC Nagpur.

What influenced you to pursue a career in the medical profession?

Why did I choose medicine as a vocation? My Maths phobia. Although I scored 98 out of 100 in Maths in eighth grade, in higher secondary school, I opted for Biology and left Maths for good. Strangely, I did not find the dissection of the cockroach, frog and earthworm repulsive but could never get over the nagging fear of or apprehension about maths. That fear influenced the career I was to pursue.

In 1973, I had applied for admission to the Government Medical College and to MGIMS, two premier medical colleges in Vidarbha. Although I was selected in both, and Wardha was my home town, I do not remember why I chose Nagpur over Sevagram.

During the late seventies, when medical aspirants at MGIMS were asked why they wanted to be a doctor, they would come out with such well-rehearsed phrases as “To serve humanity, healthier and therefore happier lives; highest pursuit of a life’s work; to save lives; want to be involved in cutting-edge research and make advancements in cancer. “These words would leave me amused. And baffled. I would also hear, “Medicine, for me, has always been a calling as well as a privilege—the ultimate opportunity to help others.” Sure enough, I did not carry such ambitions in my head! Nor was my decision to become a doctor driven by values instilled in me by my faith or my family.

When I decided to be a doctor, I never really quite understood what it meant. It just happened. It was by pure serendipity that my path to Biology took me to my destination.

During your training in medical school, which teachers influenced you the most and why?

My teachers included Dr. PN Dubey, professor of Anatomy; Mrs Vaishwanar (Biochemistry) Dr. Paranjape and Dashputra (Pharmacology), Mrs Jagtap(Pathology), Shobha Grover (Pathology), Vikram Marwah and ML Gandhe (Surgery), AM Sur (Paediatrics), Ms Shastrakar (Obstetrics and Gynaecology), Ishwarchandra (Ophthalmology), Ketkar (Preventive and Social Medicine) and Dr BS Chaubey (professor of Medicine and my guide). I mention those I remember – please forgive me if I have forgotten to include some names. I shall restrict myself to some of the lessons learnt from just two of them.

Between 1979 and 1982, I worked in Ward 23 and the kidney unit at GMC. Dr BS Chaubey, my guide, evoked indescribable awe among his residents. Trained in Nephrology in the UK, Impeccably dressed, he walked majestically as he rounded the patients, spoke elegant English, and wore discipline on his sleeves. He would park his Fiat car near ward 23 exactly a minute before it struck eight. Sure enough, he evoked a sense of awe. His aura of power, his command and confidence was absolutely nonpareil.

Erudite beyond comparison, he displayed a deep understanding of the basic sciences (he loved physiology and pathology) and used the basic sciences to formulate his thoughts.Like Muhammad Ali, his thoughts flew like a butterfly and stung like a bee. Minimalist and meticulous, he would bring his knowledge and reasoning at the patient’s bedside, and in an era in which the technology had not replaced clinical skills, would show us how to make a precise and accurate diagnosis- patient after patient.

Dr Chaubey could never suffer fools gladly. And in clinical encounters, he would scare us out of our wits.In 1980, I was his resident. During post-admission ward rounds, I narrated the history and physical signs of a patient who presented with acutely paralysed legs. It was a textbook case of acute transverse myelitis—legs, weak and numb; bladder, distended— but the diagnosis that came from my panic-struck tremulous tongue was Guillain Barre Syndrome. Dr SM Patil was associate professor in the unit. Dr Chaubey—his eyes reddened, brows furrowed, lips twisted and face visibly angry—thundered- “Patil, God save this student. Poverty of thoughts and bankruptcy of ideas”—a sentence that would stay with me for the rest of my life.

What do you think of your best contributions to MGIMS?

This year, I completed four decades in Sevagram. MGIMS has been the only institute I have worked at. I have been blessed more than I deserve. The gratitude my students and colleagues showed and the affection they showered were humbling. I’d list some of the contributions:

- In 2004, Bhavana—my wife—and I dreamed of creating a Hospital Information System at MGIMS. Our dream could have easily turned into a nightmare—those days in summers Sevagram ran out of electricity 16 hours a day, most healthcare workers were computer naive and mobiles were not born. The network connectivity was abysmal. We slogged for three years, forgetting when the day ended and nights began, to make it happen as we relentlessly strove hard to conceive, design, test and implement a digital system. We spoke to the software professionals and ensured that our Greek and their Latin doesn’t result in a miscarriage. We created a sense of belonging among all stakeholders—technicians, pharmacists, nurses, clerks, accountants, social workers, interns, residents and faculty. In turn, they helped us design a digital world to achieve what we had set our eyes on. The electronic system captures, stores, and retrieves all data related to million outpatients and 50,000 inpatients every year. Laboratories at MGIMS are paperless for a long time, and residents and consultants are able to access all laboratory test results including radiologic images—on all electronic devices anytime, anywhere on campus because of the campus-wide wireless connectivity.

- In 2002, MGIMS management decided that drug industry or medical equipment manufacturers could no longer sponsor or support any conference, seminar, or workshop in Sevagram. The guidelines also specified that Continuing Medical Education (CME) organisers could not accept advertisements or money from drug companies for publishing the proceedings, souvenirs and flyers. We did so because we felt that there is nothing called a free lunch and the medical profession must safeguard its academic independence and reinforce the integrity of science.

- In 2009, I was able to convince MGIMS to close its doors to drug representatives. It did so based on personal experience and the published research showing that drug samples, sales pitches, and free food influence physicians to prescribe medications contrary to the best evidence for clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. This initiative, limiting the potential influence of pharmaceutical and other biomedical companies in its day-to-day clinical and educational activities greatly reduced the subtle influence that the industry-doctor relationship leads to.

- MGIMS thus became the first medical institute in the country to keep the drug industry away from the sacred field of medical education. Over the last 20 years, MGIMS has shown that high-quality medical conferences can be held in medical schools if we choose to keep them simple. Much before the Medical Council of India (MCI) notified the ethical guidelines under the Indian Medical Council (Professional Conduct, Etiquette and Ethics) (Amendment) Regulations, 2015, MGIMS had already taken steps to keep the drug industry away from the hospital.

- In 2010, a low-cost drug initiative was implemented at MGIMS aimed at providing appropriate and affordable drugs to the patients. At MGIMS, patients do have to pay for their drugs, but the hospital drug policy made it possible that a patient with high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, and hyperlipidaemia could purchase required drugs at just a little over Rs .150 per month. This was made possible by making the drugs available at the procurement price, adding a 20 percent administrative cost to the procurement price. This initiative not only considerably reduced the cost of drugs but also made it possible to break the nexus between the drug industry and the hospital doctors.

- I also introduced Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) in the hospital, passionately teaching students and residents the beauty of combining art with science of medicine. I trained residents helping them use the best clinical evidence to make patient-care decisions. This practice encouraged them to examine medical rituals and traditions and replace them with practices grounded in scientific research. Residents learnt how to integrate individual clinical expertise, the best research evidence and patients’ values. In our OPDs we regularly open UpToDate to seek answers to the clinical questions. Even today, I teach my residents the virtues of choosing wisely, why “Less is More” and why our clinical decisions should be driven not by anecdotes, experiences, or distorted by our biases and prejudices but should be shaped by solid science.

- Finally, I also became a medical architect. Over the years, MGIMS asked me to work closely with architects to design ICUS, a 200-bed Medicine department building, a centre for palliative care, an administrative block, a medical store and a library, to name a few. Conscious of the adage that failure to plan is planning to fail, we designed hospital buildings that are patient-centred, and address unvoiced needs of caregivers. Combining the elements of hospital workflow with beauty and aesthetics were some of the principles that went into these projects.

What do you enjoy the most? Lectures, bedside Clinics or administration?

I was a reluctant administrator- in 2009, I was almost arm-twisted to lead the MGIMS hospital as a medical superintendent. Earlier, I had refused to head the department and had also turned down several requests to become the MGIMS dean. But as I began to soak my feet in the field of administration, I realised that I could convert challenges into opportunities. I could translate my dreams into reality. I became a key figure in decision making and was able to introduce several strategies that would make the hospital a happy place for the patients. During the decade that I occupied this post I earned more bouquets and brickbats than I deserve.

I’m equally at home with bedside clinics. During my clinics, I often teach the history of medicine— digging Laennec, Auenbrugger, Vesalius, Einthoven and Roentgen from their graves. I also make students aware of the impact of social and economic factors that shape our decision making. I tell them stories from Atul Gawande’s and Ranjana Srivastava’s world. I often introduce them to books that can influence their thought process. I also explain to them the pluses and minuses of history and physical examination for making a diagnosis. And I also discuss things we were never taught during our residency: ethics and economics, as an example.

Lectures? Yes, during my early and mid-days, I enjoyed preparing hard for lectures. I started with chalk and black-board, moved on to transparencies, and then shifted to the PowerPoint, spending several hours designing my slides, remembering them verbatim and delivering lectures in the undergraduate classes. Realisation has begun to dawn on me that lectures have serious limitations.

Your opinion on Covid 19 management

In the eyes of Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Covid is a black swan. The beginning of this pandemic caught the whole world unaware and unprepared. There was chaos among the doctors, and panic among the people. There was tremendous pressure on the scientific community to identify effective treatment soon. As early as in April 2020, my colleagues and I wrote a piece in Lancet Infectious Disease strongly criticizing the ICMR for signing off on the health ministry’s decision to recommend hydroxychloroquine as a Covid therapy. We argued that all scientific reasoning cannot be abandoned citing desperate times. All through the Covid period, I spoke extensively—arguing why science is the best weapon we have in our armour to fight Covid. Many pharmaceutical companies precociously claimed success for their respective molecules, publishing data limited to press-releases, and gained expedited approvals. We pointed out why such hasty practices shall do more harm than good.

Such reports, along with research data about early suggestions of benefits were eagerly amplified by the media. The administrations too were eager to present a glimmer of hope to the people, and echoed these sentiments. As a result, public opinion was greatly influenced by anecdotes and expectations, thus greatly amplifying the perceived efficacy of treatments. The scientific community repeatedly cautioned against inflated claims of successful treatment, however, they were largely ignored.

I used Twitter—close to 14000 people follow me—to argue against high cost,-low value therapies gaining a foothold in the hospitals. We critically reviewed the evidence for—or against the use of antivirals, anti-inflammatory strategies, human plasma and monoclonal antibodies. We also cautioned that newer therapies such as Paxlovid, Molnupiravir, Fluvoxamine, and Monoclonal antibodies have limited indications and many times their risks outweigh small benefits. In Sevagram I became a champion of the “Less is More” approach and we minimised the drugs for treating the entire spectrum of Covid. Thus, our hospital hardly used medicines such as Ivermectin, HCQ, Favipiravir, convalescent plasma and Remdesivir during the pandemic.

I believe that all our decisions related to Covid 19—diagnosis, prevention, treatment and prognostication—should be governed by well-designed and well-conducted published high-quality research. Individual opinions are packed with biases; anecdotes do more harm than good and even senior scientific bodies are wrong more often than the public thinks they are. We wrote in a book on Covid that “Desperate times such as these do not warrant loosening of regulations. They actually warrant more meticulous research. Faster, erroneous inferences are likely to cause more damage than relatively slower, accurate conclusions.”

Do you think every physician should have working knowledge of Clinical Epidemiology and why?

Should doctors be trained in clinical epidemiology? Absolutely. How I wish during my residency at GMC Nagpur I should have been exposed to the art and science of epidemiology and evidence-based medicine. I had huge gaps in knowledge when I reached mid-career stage, not knowing how to read and interpret a paper published in the Lancet, JAMA or NEJM. I did not know when and why to order a test; more importantly when not to order a test. I was not aware of the harms of routine screening tests. Nor did I know how big pharma systematically impacts our prescriptions. Today, no doctor should practise unless s(he) is trained in basic medical statistics, epidemiology and evidence- based medicine. They must know how to ask an answerable clinical question, how to search for and critically appraise the evidence, and how to bring it at the patient’s bedside. Isn’t it a national shame that we are designing doctors who cannot read a table, interpret a Kaplan Meier curve, are unable to critically appraise a study and are all at sea when P values and confidence intervals stare them in their eyes?

What is your message to medical teachers?

To be honest, what I had not realised then but did eventually, was that some of my teachers were not what I would’ve wished them to be. I also deeply regret that I emulated a few of them blindly—bringing their anger, indifference, impatience, bias, contempt and arrogance to the patients’ bedside. It took me quite a while to recognize these awful attributes.

Teachers must shed their arrogance, hubris, and contempt for others. They ought to remember William Osler’s aphorism that Medicine is a science of uncertainty and an art of probability. We must always be conscious of the gap between evidence and actual practice. As Dr Sushila Nayar, the founder of MGIMS, would say, doctors must practise honesty, humanity and humility in the classrooms and hospital wards. We must also remember the line attributed to the University of Chicago president, “”Half of everything we teach you is wrong. Unfortunately, we don’t know which half.”

Medical teachers come in several flavours—the good, the bad, and the ugly. Medical students look forward to teachers who are enthusiastic, inspiring, approachable, and generous with their time. Good teachers really enjoy teaching students and students love being taught by them. In a NEET era, students might not like teachers stressing the art and science of medicine, but years later most of them might really remember the benefits of learning at the bedside. Hopefully some of the good clinical work teachers are doing shall get rubbed off on their students.

William Osler famously said, “ He who studies medicine without books sails an uncharted sea, but he who studies medicine without patients does not go to sea at all.” This adage holds special relevance in the NEET era. Also keep in mind Doug Altman’s famous sentence, “We need less research, better research, and research done for the right reasons.” (BMJ 1994)Finally, Steve Jobs’ famous message at Stanford University in 2005, “Stay hungry, stay foolish” applies as much to the medical students and teachers, as to the software professionals

What are your non-medical Interests? We are aware of your passion for books and cycling. Tell us more about that.

- Books. As a child, I longed for books, seeking them everywhere and seizing every opportunity at reading them. Over the years, the book addiction has grown—converting me into an obsessive-compulsive bookworm. In the last six months, I read several autobiographies (Dilip Kumar, Dev Anand, Raj Kapoor, SD and RD Burman, Waheeda Rehman, Meena Kumari, Dilip Shanghavi, Indra Nooyi, Chandu Borde, GR Vishwanath, VVS Laxman; Warren Buffet, Charlie Munger) and works of JK Rowling, Scott Adams, Daniel Kannmahnn, Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Eric Topol, Gerome Gropmann, and Ramchandra Guha, among others. I have an abiding interest in the history of medicine and medical ethics.

- Cricket. Although cricket didn’t run in the blood, and I never played serious cricket, this game fascinated me from my childhood days. In 1969—I had not even entered the teen age—I chanced to see India vs. New Zealand test match at Vidarbha Cricket Association stadium. I began to compute batting averages and would closely watch how the ball was delivered, its angle, spin, velocity, and trajectory. The Men in Blue no longer evoke the same respect as the cricketers of yore. Ever since IPL kicked off—a big-money sporting spectacle—cricket has become a glitzy Bollywood movie. As Rajdeep Sardesai wrote in his recent book, The Great Indian Cricket Story, modern cricket has become the biggest circus in town.

- Cycling. A maturity-onset cyclist, I began riding a bicycle a few years after I had undergone a mid-fifty angioplasty. I have done over 12 000 km on saddle—successfully completing long distance Endurance Cycling with rides of 200 and 300 kms (Brevets) on highways criss-crossing Nagpur. Every day I cycle to work. As a leisure-time exercise, cycling helps me keep my coronaries clean and unwind from the stresses of administration.

If you are asked to list the most defining moments of life, what are they?

- In March 1979, I got an MD medicine seat at GMC Nagpur and was assigned to Unit 4 Medicine. I began working in wards 37 and 38. Hardly had I got into unit 4 than I was ordered to report to Dr BS Chaubey, then head of the department of Medicine. I am still not certain—possibly nobody knows— what made him hand-pick me, change my unit and guide and take me under his tutelage. Those days gossip on this issue set the hostels, hospital corridors and coffee houses abuzz. Dr Chaubey became my official guide. This gesture— how can I ever forget it—was indeed a defining moment in my career. I was elated, but felt equally nervous and anxious. What if I fail to meet high expectations he had set for me? To earn his approval, I spent most of my waking time in ward 23 and the kidney unit, writing detailed histories and physical exam findings of over 50 patients admitted to the unit; charting the blood pressure, electrolytes and urine output of patients with chronic kidney disease with four colourful pens; doing complete blood counts and urine microscopy in the ward side-lab and ensuring that not only all orders were followed to the hilt but also the case records were impeccably complete. Dr Chaubey was known to have acquired a stiff upper lip from England—he seldom appreciated, barely praised and scarcely recognised good work. Yet the two years that I spent in his unit—honing the craft—helped me figure out what went in his mind when his stethoscope artfully descended on the patient’s chest. Those two years had a huge impact on my professional development.

- In the summer of 1982, two months after obtaining my MD, I was appointed senior resident at MGIMS on a princely salary of Rs 825 every month. Little did I realise then that I shall be spending my entire life in Sevagram. The campus gave me enough opportunities to teach, do research, care for patients and soak feet in administration. Hundreds of medical students and residents became life-long friends. MGIMS sensitised me to the plight of the less fortunate and inspired a desire to emulate those who were my role models. But for Sevagram, I might have degenerated into just a mundane medical teacher, a run-of-the-mill private practitioner or an administrator churning out insipid, shallow work.

- In the fall of 2004, as my career progressed and my children grew up, I earned a scholarship to do epidemiology and public health at UC Berkeley. I was back to classrooms—sitting through lectures, doing homework assignments, participating in group activities, preparing posters, taking exams and writing a MPH thesis. I count myself lucky to have been taught with some of the best epidemiologists in the USA, and to have rubbed shoulders with them. That stint helped me understand what it takes to do medical research—skills that I began to teach and apply at the patients’ bedside.

- In 2014, I took it upon myself to write a book on the life and times of my class: GMC 1973. It took me a few years to discover the forgotten gems of the class of 1973, contact almost every classmate, talk with them extensively and document their story. In 2020, I finished the book—a book that describes the joyous as well as difficult moments of my classmates. Their struggle and success. How they navigated their ways from small villages in Vidarbha to the heights of medical practice. I didn’t want this work to be a dull compilation of facts; instead, I brought the narrative to life in this 700- pages book. I opened the windows into the life, career and families of the 204 students. For me, this book was a journey to discover and relive the class of 1973 story- a story of ambitions, sacrifices, opportunities, talent, achievements and also a story of dejections, disappointments and (broken) dreams. I used my statistical skills to embellish the book with interesting titbits about the class.

What was your experience while treating Vinoba Bhave and handling multiple super VIPs from Congress who used to visit Vinoba Bhave?

In the winter of 1983, barely a year-and-half after joining MGIMS, Dr BS Chaubey asked me to look after Vinoba Bhave, then an 87-year-old spiritual heir to Mahatma Gandhi. Vinobaji lived in Pavnar, 8 km from Sevagram. He had taken acutely ill, and received a diagnosis of pneumonia or pulmonary embolism—without a blood test or a chest radiograph. Ramesh Mundle joined me and we lived in the Pavnar Ashram for almost a fortnight. We spent the day checking his vitals; auscultating the lungs; injecting penicillin, aminophylline and heparin in his veins and preparing and displaying daily health bulletins. Vinobaji consented for medical treatment in his Ashram for a few days but then starved to death. Aware of the frailties and limitations of modern medicine, Vinobaji chose the manner and the time of his death and decided to let his life slip away. Death held no terror to him.

He seemed to have thought a great deal about death, as he did about how to live a purposeful life. Those were the days when no soul would leave the ICU of GMC Nagpur without the ribs of the dying broken or heart punctured with a needle. Every straight line on the monitor deserved the ritual of a (futile) cardio-pulmonary resuscitation. Mundle and I were trained to save every life in our ICUs; we had not learnt the art of letting someone go. Vinobaji’s preparedness for death was a humbling experience to both of us.

The then Prime Minister of India, Indira Gandhi, came to see him twice, as did Rajiv Gandhi, and several national leaders. We were touched by Indiraji’s warmth and humility—she’d sit cross-legged to lunch with us, would wash her dining plates and would ponder the question when we asked her how to balance patients’ rights vis a vis doctor’s duty. Thankfully, television, twitter, WhatsApp and media channels were not born then, and journalists were not trained to to break the news. Free from the probing eyes of journalists, bureaucrats and politicians, we came to terms with death as the final truth and learnt that death, far from being a depressing defeat, can sometimes be a vivacious victory too.