Bai—this is how most Marwaris address their mother. We too followed the tradition. Born to Shri Shriram and Gopi Bai Mundra on 5 January 1925, she was the first of the five children. She came from Barshi, a town in Solapur district of Western Maharashtra. As was the norm those days, she completed her primary school education and didn’t study further. Perhaps, from the shop, her father could not afford to educate a girl child.

Marriage

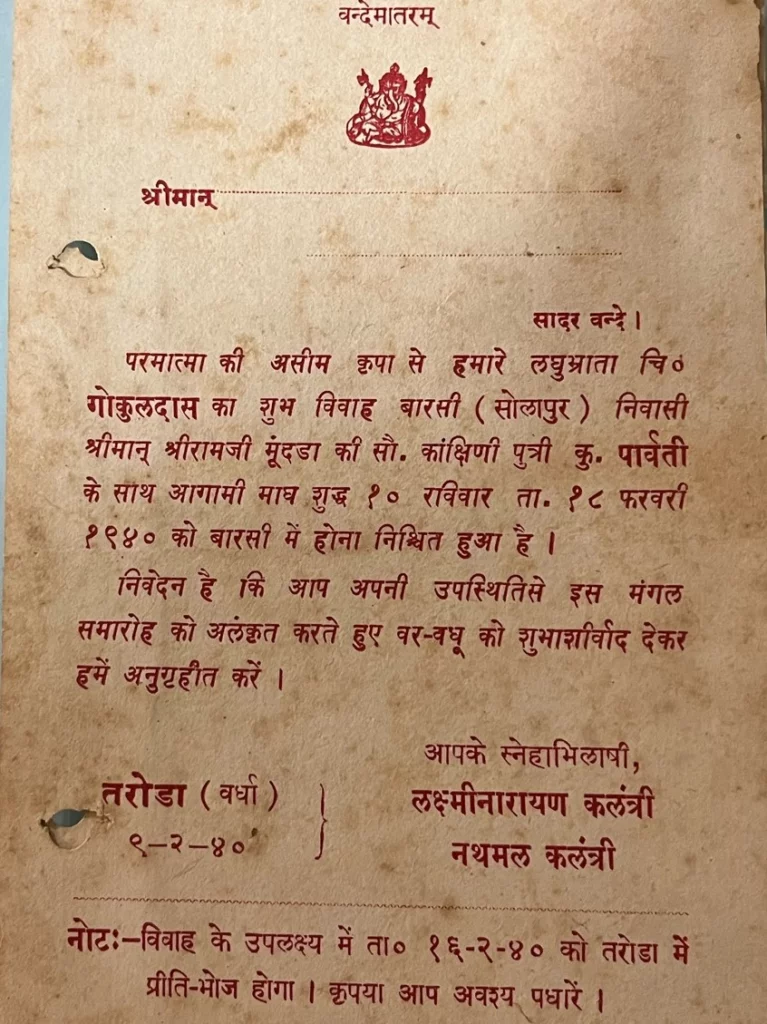

She was only 15-year-old when Mr Dwarkadas Bhaiyya, Wardha and Mr Sukhdev Singhi from Solapur moved the proposal. Nanaji arranged her marriage with my father. The year was 1940. Her marriage always puzzled me. I often asked my sisters how this marriage happened? First, Barshi was located 850 km west of Wardha and one had to endure three-days two-nights journey and change as many trains from Wardha—at Daund, Manmad and Kurduvadi stations to reach Barshi. Second, there was a gap of nine years between the spouses, which was not unusual in those days. Third, Bai owed her origins to Badi Marwad and Bhaiji had roots in Pokhran-Phalodi—both in Rajasthan. Although they shared a common language—Marwadi—their dialects differed considerably. Fourth, my father imposed a condition for the marriage, that make them feel flabbergasted. “I want the bride not to wear a ghoonghat during the entire wedding ceremony and after marriage,” my father firmly, and sternly, demanded.

My Nanaji ran a shop in Barshi selling soaps, biscuits, and tea leaves, but was more interested in and dedicated to spiritual and religious activities. He lived simply, was devout and was supremely focused on ईश्वर भक्ति. He was orthodox and religious who followed every tradition to the tee. My Nanaji and Naniji and their elders didn’t know how to respond. A girl without a ghoonghat was unthinkable in the society, more so when she was marrying. ” What made you say Yes to a boy whose face is so dark, has no parents, hasn’t studied beyond seventh grade, is yet to find his roots, has no roof over his head, and wants Parvati not to cover her head with a veil? How can my daughter adjust in such a society? And she is going 500 miles away?”my Naniji asked Nanaji. She was understandably perplexed. Nanaji had no answer. He had already committed. They had a hard time coming to terms with these demands. Eventually, they did.

Finally, my father had his way. Perhaps this was the first wedding in Barshi with a bride not masking her face with a ghoonghat. It took place on 18 February 1940.

We have carefully preserved the wedding card—so simple, and so beautifully worded. In 1940, my mother— her face not hidden by the traditional ghoonghat, a head covering or headscarf, worn by married Hindu women to cover their heads, and often their faces— took seven vows or Satapadi: a very unusual step at that time.

My father—he lost his parents when he was barely 5 years old—was doing a small job in the local Bachhraj group, Wardha. Born in 1916, he moved from Pimpalkhuta, Taroda and Kharangana Morangana— villages to the north of Wardha district— before he arrived in Wardha seeking a job. Nathmal— his elder brother stayed back in Taroda where he owned a small grocery shop and looked after some land.

मारवाड़ी मोहल्ला: पहला घर

The 15-year-old girl was separated from parents. Her mother-in-law and father-in-law had died long ago; she had four sister-in-laws, three of them elder to my father. The very thought of surviving in a completely unfamiliar land was enough to give Bai nightmares. She would often cry asking her parents to take her back to Barshi. After marriage, her kakaji came to drop her to Wardha. Aware that she won’t let him go back, he discretely left her while she was sleeping. When she woke up, she ran around like a scared deer running in the forest, frantically searching for him. She finally found that her Kakaji had gone to Barshi, and began to cry—tears streaming down her cheeks.

Soon after marriage, my father rented a small house in Marwari mohalla—now thick in the market area. His neighbours were Mr Murlidhar Saraf, Dwarkadas Saraf, Surajmal and Pachibai Agrawal (Belawala), Chaubey, Tibdewal, Mr Satyanarayan Goenka, Mr Durgadas and Yashoda Gandhi, and Mr Nare. The house had a reputation of being haunted by ghosts, and my father, who dismissed such beliefs with the contempt they deserved, went ahead and rented the house. For fifteen years she lived there and five of her six children were born—four of them from Sutika gruh, Wardha. In 1955 my father bought her a stove that ran on gas, but Bai was so used to the (dis)comfort of the smoke-emitting chullah that she returned the stove and the gas connection! Then he bought her a smokeless Magan Chullah. It cost him Rs 10. This time Bai didn’t show Chullah the door.

Those were the days, when Bai ran a full house without a cooker, mixer, grinder, refrigerator, microwave or cooking range, telephone and electricity but never seem to have run into a problem. Life was stressful and crazy and chaotic. There were chores left unfinished. The to-do list items didn’t exist those days, but if they did, I am sure they were left unchecked.

Interesting, once Bhaiji bought her half-ticket for Barshi to Wardha train travel. Although she was married, her delicate frame made her look very small. Every summer, she and kids would go to Barshi, carefully packing her large black tin पेटी for the journey that would last two-and-half days. In those days, the diesel and electric engines had not replaced the steam engines and trains moved on meter gauge and narrow gauge tracks. Today a train takes just 30 minutes to reach Barshi from Kurduwadi; in those days, it used to take no less than three hours. In 1955, fares of passenger trains were standardised at 30 paise, 16 paise, 9 paise, and 5 paise per mile for 1st, 2nd, Inter, and 3rd class, respectively.

घर नंबर २: बजाज इलेक्ट्रिकल्स

In 1955, my father found a new home in the Bajaj Electricals campus, near Gandhi chowk. We paid a small rent for the house that belonged to the Bajaj group. I was born in this home two years later. Also, my elder sister’s (Asha) marriage took place from this home. In 1963, we moved into a house in Bachhraj factories— cotton and ginning press— also my father’s workplace. Pushpa, my second sister, had her marriage solemnized here in May 1965. I went to the Cradock High School, later renamed Mahatma Gandhi Vidyalaya, from 1965 to 1968 from this home.

Finding her Footing

My mother was in her mid-teens when she married. The burden of managing a household fell on her young shoulders. She had no idea how to cook, and how to run a home. She had to acquire these skills from her sister-in-laws. She partly learned from them and partly taught herself how to knead and roll dough to make the चपाती that my father wanted steaming hot. She learned how to make perfect सब्जी, and दाल-चावल. She also learnt how to roast a पापड़ without a single burn mark over it. And she learned how to make खीर, बादाम का हलुवा, पूरण पोली, and दाल- बाटी. She specialised in making mouth-watering आलू भात और मीठे चावल— and would serve these two delicacies whenever any guest dropped in. My favourite was केले का कालवन— banana mashed and mixed with milk and sugar. And for Om, she would make it a point to prepare गट्टे की खिचड़ी.

“She not only quickly acquired the art of cooking, but honed her skills in no time. She was super-fast— her jugglery of serving steaming hot Phulka was worth watching. Bhaiji used to sit cross-legged for his lunches and dinners, and Bai would join him as he finished his food. Bhaiji would sit patiently until Bai too finished her dinner,” Badibai recalled on 17 December 2022.

She belonged to an era in which society constantly tried to define women and who they should be. She also learnt how to wash shirts, dhotis, saris, bedsheets and children’s uniforms and how to hang them to dry. She ironed the correct creases with starch she made from rice flour stirred with water over the wooden fire. She would also wash the dishes, put away them, grind masalas, and churn the buttermilk in the old manual way to separate the butter. She would use the milk for the yogurt, buttermilk, butter and ghee. We, the children would also take our turn in churning the buttermilk—we used to call it झगड़- बिलोना!

Every year, my father would buy fifty yards or so of material, hire a local tailor and order fresh uniforms for the schools to come. I can recall Bai telling the tailor to sew everything two sizes bigger than our correct sizes so that we could grow into it. Although the clothes were quite unshapely, we thought that they were modern and treasured them. In April 1969, I was in the seventh grade, and Ashok was to marry Kanta Bhabhi. Bai got a pair of shirt and half-pants stitched from the Modern Tailor, near Nirmal bakery. And I felt so proud flaunting my prized possession.

Lunches and dinners—she would single-handedly prepare them. She would always serve us first and eat later. After dinner, she had the usual household chores to do, before the lights were out. Of note, for the first year or so of her married life, there was no electricity at home, and lanterns and candles would be used to lit the home. Mosquitos buzzed around and feasted on our skins. Capturing mosquitoes with a clap of the hands was a required survival skill.

६ बच्चों की माँ

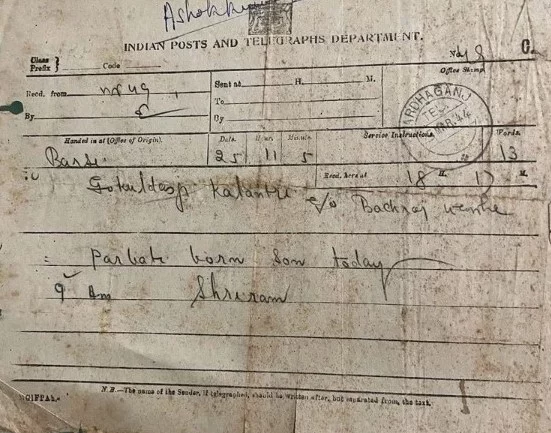

Eighty years ago, an average mother had six children, and often more. Bai was no exception. Between 1942 and 1957, she delivered four boys and two girls, all at home. In 1942, Asha, my elder sister, was born in Barshi town. Subsequently Ashok (1944), Pushpa ( 1946), Om (1948), JP (1951) and I (1957) were born to her.

Nanaji wrote a letter to my father, announcing the birth of a baby girl. ” There were some problems during the delivery,” he wrote, ” and we had to call a doctor and a nurse. Now she is well, and there is no reason to worry,” he added. Bai’s kakaji also wrote my father a letter informing him of the arrival of the baby girl. Interestingly, in the same letter he expresses his deep sorrow at the sudden demise of Shri Jamnalal Bajaj, the great freedom fighter and owner of the Bajaj group my father was serving. He died of stroke on 11 February 1942, bringing to an end a life lived dedicatedly and unselfishly for the country, barely eleven days after Asha was born. Those were the days, when national events moved people as much as the personal events and milestones. He felt happy that a daughter was born in the family, but was equally sad at the demise of Jamnalal Bajaj.

Asha, my sister, was fifteen-year-old when I was born—the youngest sibling. Much to the joy of my parents, a boy had been born at 6:27 am on 15 August 1957. Birthdays are always special, but for my parents, as chance would have it, the very thought of celebrating it on August 15—India’s Independence Day—was a double joy. It was only a day earlier that a baby boy was born to Bai’s cousin in Barshi and my arrival on 15th August made my parents score a brownie point. I might not have been born with a silver spoon in my mouth, but surely I was born with a flag in my hand.

Devendra, my birth name, was quickly changed by Bhaiji to Shriprakash—in line with Omprakash and Jaiprakash, my elder brothers. I don’t know if my parents ever called me Shriprakash. Perhaps Bhaiji was not comfortable with such a grandiloquent name. He favoured something shorter, and decided that I should be called SP, a name that stuck on me all my life. From my very early years, Bai, Bhaiji, my sisters and brothers started calling me SP, as did my friends and later my wife and in-laws too. I often wonder how easily Bai could accept and adjust to this English abbreviation.

Asha and Pushpa, my sisters, tell me that when I was four-or five years old, I would ask Bai to wrap a dhoti around my waist, apply tilak and watch me perform some Puja. Much to her amusement, I would also tell her that my real parents were on Kailash Mountain—Shankar and Parvati—and although my mother shared the same name, she was not my real mother!

When I was a kid, birthdays were not celebrated the way they are today. There were no posters, banners or balloons all around the room. There were no midnight happy birthday calls. Nor a midnight cake cutting. No wild celebrations. No gifts to be exchanged. On my birthday, Bai would wake me up. I’d make my way into the bathroom, rub my body with Haldi and Milk. She’d give me a new shirt and a half-pant, stitched locally. Next, she would make me sit on a wooden plank, apply tilak on my forehead, make me fold my hands to the images of the Shriram and Sita and offer a homemade pedha. There were no birthday wishes, no cards, nor festive displays, nor birthday parties. I’m pretty sure she loved my birthday more than her own—she never remembered her birthday, nor was her birthday ever celebrated.

I am not sure if children ever possessed toy and dolls. Her grandchildren and I played कंचे, गिल्ली-डंडा, लघोरी, धाबा- धुबी, छुपा-छुपी,नदी-पहाड़ —games that required no money. As for cricket, the wooden plank from the kitchen would double up as stumps, मोगरी would become a bat and torn pieces of old cloth tightly wrapped by a सुतली would be used as a ball.

जयश्री भवन

From 1968, till her death Bai lived in Jaishree Bhavan—located near Indira square. My father had bought this property, then Kesrimal Kanya Shala, in 1968. We, the four brothers, grew, went to schools and colleges and got married from this home.

Ours was a large airy house where more than a dozen grandchildren would gather for festivals or summer holidays. Our verandah boasted of a large swing (we called it बँगाई) with four long chains that were anchored into the ceiling. The green swing, with its gentle glide back and forth, is vividly etched on my mind. My father used to sit on the swing, and so did Bai.

नानी का घर

Come summer, and her daughters and grandchildren would arrive in Wardha. They would spend two months at the grandparents’ home. Their never ending activities would be both a source of joy as well as nuisance to my mother. The house would suddenly turn very noisy, with a lot of laughing, arguing, shouting and fighting. The grandchildren were always in motion, laughing merrily and carrying on to the next game—setting the house abuzz. They played hide-and-seek, climbed trees, plucked off Phalse (Grewia asiatica) from a tree, and picked the guavas that grew in the garden in the backyard of the house. They ate on the floor, sitting cross-legged with their Mamiji serving them hot phulkas, daal, sabji and aam ka ras. Aalok and Manoj, her grandchildren, would tease, torment and trouble their Mamis in the kitchen—they would suddenly turn into gluttons, exhausting all their Mamis had cooked and making them cook again.

In the night the beds were lined up in the open space. The day temperatures in May often hovered around 115 F. Children would sprinkle water on and around their beds, hoping this simple trick would cool the place.

Bai was always in motion—cooking, cleaning, loudly barking out orders, keeping a tight leash on her Bahus, admonishing the servants, feeding others and completing the household chores. Conscious of her seniority, as soon as her first Bahu finished her BA from the local arts college, she decided to stop working in the kitchen.

Everybody contributed in the kitchen—we, the children, would wash hundreds of desi Aams, clean them, peel them off, and squeeze them to prepare the favourite summer dish—आम का रस. We would also help the family prepare mango pickle. We would wash the raw green mangoes. Dry them. Cut them into small pieces. Bai would keep a big steel vessel, would add turmeric powder and salt and keep it overnight. Next day, she would grind mustard seeds to make fine powder, and fry methi seeds until they turned crisp. Then they were crushed. She would add rai powder, methi seeds powder and chilli powder to the raw mangoes. She would mix them well. Next day, she would take oil in a pan, heat it and add mustard seeds. When they started sputtering, she would add hing and turmeric powder, allow them to cool, and pour oil on the raw mangoes mixed with all spices. The home-made pickle was ready!

Even more interesting was her recipe for making Papad. She would use gram flour, chilli powder, garlic and ginger paste, turmeric and salt. Then she would pour water in the mixture and knead it into a smooth dough. Our task was to divide the dough into small equal size portions. Her daughters and Bahus would use a rolling pin, flatten the dough pieces into a circle and would repeat until they finished the other portions too. Badibai tells me that earlier she and Pushpa would roll hundred Papads provided Bai would make कच्चा चिवड़ा for them after they finished rolling. We, the children, would actively take part in the Papad making process simply because we would get a chance to eat papad लोया! And we devoured them as if we were chronically hungry.

And how can we forget the wheat cleaning process? I have lost count of the number of wheat bags that my father would buy every summer. Our task was to separate wheat from chaff, pick up small stones in the wheat and ensure that the wheat was free from the contaminants. Each child and grandchild would be paid one anna (six paise) for cleaning eight Payalis of wheat—a big amount for us! And lest I forget, our favourite pastime was stealing इमली.

We also used to have a couple of cows in the backyard of our home. Every morning Venkati Waghmare— he also used to work in the Laxminarayan Temple—would come to our home to milk the cows. Bai would ask the children to drink fresh unboiled milk—called धारोष्ण दूध. She would put a बताशा in the milk glass and give one anna for drinking a glass. She would also ask Om and Pushpa to buy जलेबी from Dinanath Chudiwale’s shop which came their way to school. Come winter, she would buy a glass of नीरा for each of her kid— each glass would cost two paise.

Every winter, Bai would wake up at 4 am and prepare बादाम का हलुवा. She would get the blanket or a quilt off our body and ask us to eat the sweet dish and quickly go to bed with our face covered by the thick blanket. This is how the sweet dish worked and enhanced immunity, she thought.

After we shifted to the Bajaj Electricals home, Bai befriended Yashoda (wife of Durgadasji Gandhi), wife of Nathmalji Sevak and one more.

Those days, there were very few shops in the town. Grocery would come from Appaji Maradwar; cloth from Bansilalji Patni (Durgadasji Gandhi used to work with him), Hinganghat Wala shop, and Devidas Bhau Wakare’s shop; footwear from the Flex shop; books from Kelkar; and hardware from Ghulam Ali.

She never went to the market to buy fruit or vegetables. This task was first assigned to Uttambhau and later to Asha. Badibai would go the Sabji Mandi, buy vegetables and settle the bills. She would also go to the grocery shop that Appaji Maradwar ran to buy groceries.

In 1960, Bhaiji took Bai for a चार धाम यात्रा: a pilgrimage of four holy sites—Yamunotri, Gangotri, Kedarnath and Badrinath. They also visited Jagannath Puri where the entire party went to the seashore. Suddenly the sea waves rose and took Bai along. Fortunately, the tide fell back and brought her back to the shore! This was the first time she sat in an aeroplane and tried a horse.

Bai had one weakness. Movies. Whenever she spotted an occasion, she would go to the local theatres to watch a movie. In January 1962, when Badibai was pregnant, she took her to watch Sampoorna Ramayana, a 1961 mythological film starring Mahipal and Anita Guha as Rama and Sita respectively. Badibai began to develop labour pains in the theatre—she delivered Archana the next day. “ Sitaji has arrived in our home,” was Bai’s spontaneous response. Then she made a telephonic call to Bhaiji and tried to fool him, saying that a baby boy was born to Asha. Bhaiji quickly corrected her saying that it had to be a girl, and not a boy. “How could you know that,” Bai asked him. “Your voice was not strong enough to suggest a boy. I could figure out that you were testing me,” my father said.

Archana was born on 23 January 1962. It was an election year. Kamalnayanji Bajaj was the Wardha Lok Sabha constituency candidate from the Congress party. Bhaiji also looked after his local logistics and election campaigns. Every day he would send Bai to Sutika Grih in a different Ambassador—a fact that made the local doctor wonder who the woman was.

In 1965, Anand (Badibai’s son) was barely a year-and-a-half old. Badibai requested Bai to keep Anand with her because he was not keeping well in Bhopal. She was reluctant to keep a sick child with her. It took Bhaiji a lot of time to persuade her that if Anand was to survive his childhood sickness, Wardha offered him the best option. A few months later, Pushpa Jiji got married. Anand grew so fond of Bai that he refused to acknowledge his real mother. Once Badibai took off a sari from Bai’s cupboard. As soon as Anand saw this, he asked her to take it off and put it back in the cupboard. Bai became his mother, so much so that when Badibai would come for a month-long holiday in Wardha, he would ask Bai when Badibai would go! In the winter of 1966, our Tauji (Nathmalji Kalantri) died. Soon, Uttambhau’s two children, Sunita and Sanjay, aged nine and five, too died young of an infectious disease that was sweeping the district. These sudden deaths unnerved Bai. She requested Jijaji to take Anand back. By then, Anand was in the pink of health, thanks to Bai and Jiji’s tender loving care.

In 1971, Bai also went to Bhopal. Badibai was pregnant with Amit then. She stayed with her for two weeks until Badibai’s Jethani arrived and returned back home only after handing over the charge to her.

In 1973, when I was admitted to the Medical College, Nagpur, she was understandably concerned. I was her pampered baby- the one who had never moved out of home. She would write me a weekly post card, asking me to drink two glasses of milk, eat fresh fruits and almonds, cashew nuts, kishmish and akhrot she would periodically send me. Whenever I went home, she would pack my bag with a large box of लड्डू. She would ask me to eat alone and not to share them with my friends. When she came to know that my classmates would finish off the entire dabba in no time, she told me how painstakingly she made those sweets. I had difficulty explaining to her why sweets need to be shared in the hostel.

Although she came from a religious family, Bai never performed an elaborate Pooja. All she would do was to simply apply Tilak to the God’s image, offer flowers and fold her hands. She would go to Sai mandir, almost every day. After my father passed away, she began regularly reading Kalyan, a religious magazine and learnt by heart a full book of bhajans. She would sing them beautifully whenever we asked her. She loved going to religious discourses, though. She attended Bhagwat from Dongre Maharaj at Nagpur and Yavatmal, and Barshi and Ramayana from Alka Shri at Yavatmal. She also attended Ramesh Oza’s Bhagwat in Wardha in the late nineties.

Which homes would she visit? Not many. After Diwali, she would go to Rameshwarji Bajaj, Ghanshyam Bajaj, Kunjilalji Jajodia, Shriram Poddar, Murlidhar Saraf, Chiranjilalji Badjate, Professor RK Vora, Champalalji Fattepuria, Professor Shri Narayan Agrawal and Durgadasji Gandhi.

Health issues

In the late fifties she developed chronic amebiasis. Professor RK Vora—he taught economics at GS College of Commerce, Wardha—who used to come to our home almost daily, advised her to try tobacco, betel nut and Paan. This would take care of her nagging abdominal pains, he said. Naive as she was, she took the advice to her heart. Little did she realise that she’d develop a life-long dependance on tobacco and Paan by acting on his suggestion. “She would often chew dozens of Paans every day. She carefully stocked Paan, Chuna, Kattha and Supari in her kitchen. It was only after Bhaiji died, that she stopped chewing Paan and tobacco, never touching them again,” Badibai told me.

In the winter of 1963, in the Bajaj Electricals home, Bai fractured her four ribs. She wanted to air dry Moong ki badi. Keeping one foot on a window, she tried to set the other on the tin roof, when she imbalanced herself, slipped and fell. She broke her four ribs. Somebody ran to fetch the doctor but before the doctor could examine her, Professor RK Vora accurately predicted that her four ribs have gone. The pain must have been excruciating and it took a few weeks for Bai to recover. This was in 1963 and there were no orthopedicians in Wardha then. Anand was just a month old then and Badibai had to cancel her Indore trip.

In 1970, at age 45, Bai suddenly became sick. She developed what looks like menopausal symptoms—hot flushes, sweating, palpitations, and sleepless nights. Bhaiji sensed the danger and wondered if her health issues were senior enough to merit a consultation from a MD physician from Nagpur. Dr Warhadpande, a local RMP physician, used to see her but she fell seriously ill. Dr BC Chandak, Jiji’s brother-in-law and an intern at Medical College, managed to get Dr KL Jain, then a noted physician from Nagpur. He came by his own car, examined her, took a bedside ECG in our home and prescribed some medicines. Perhaps it was a placebo effect of a great physician from Nagpur paying her a home visit—she immediately began to feel better. Bhaiji was so relieved! Wardha city was abuzz with the gossip that Dr KL Jain from Nagpur personally came to see her. For several months, he ordered garden fresh fruits from Nagpur for her.

Ram Singh Ji Vaidya ran an Ayurvedic clinic in the local Laxminarayan Temple. An extended family member, he used to come daily to our home to drink water. And then he would examine the pulse and offer his sure-success medicines to the family members. He was a source of great solace to Bai.

In January 1997, Bai had her first heart attack. Nikita, Aalok’s daughter was born on 20 December 1996, and a fortnight later her heart attack brought her to the ICU of Sevagram medical college. She received streptokinase, a clot buster for the heart attack.

On 29 December 2000, she had another heart attack. She was admitted to the ICU of Sevagram medical college hospital for four days and was administered thrombolytic therapy ( streptokinase) within three hours of chest pain. High blood pressure apart, she had no risk factors to account for heart attack. She was remarkably free of angina and breathing difficulty. In the final leg of her life, she developed memory loss and would often fail to recognize me. Pushpa, her daughter, became Bahuji; Kanta, her daughter-in-law, Bai; Aruna, Shahapur wali Bhabhiji and I, Kanwar saab, the son-in-law. She began to forget that she had eaten lunch. “In a way forgetfulness was a bliss for her. She could no longer remember who said what,where, when and why. The memory loss protected her from the emotional turmoil,” Badibai felt.

Bhaiji passed away in 1986

In December 1986, Bhaiji passed away of a heart attack. He was 70. Barely a fortnight ago, he had organised Archana’s grand wedding in Wardha and had called almost all relatives and loved ones for the wedding. As soon as Badibai learnt that Bhaiji was no more, she and Anand took a night train from Bhopal to Nagpur and another train to reach Wardha. By 7 am, they were in Wardha. Pushpa Jiji accompanied Bade Jijaji and came by GT express by noon. Bai wept inconsolably. Her eyes had turned dry—she had exhausted her tears. She was speechless. The thought that the 46-year-old association would end so suddenly was beyond her imagination. She felt numb, shocked and fearful. She adored him beyond measure and his sudden death left her literally speechless for days afterwards. She was so overwhelmed with grief and sorrow that she would often cry—trying to hide her tears by covering herself in a blanket. It took her awhile to absorb the shock and sorrow of my father’s death. Sixty-one year-old then, she lived for two decades after Bhaiji died, mostly at Jaishree Bhavan in Wardha.

Songs, Bhajans and Movies

My mother was a slight woman of four feet ten or so. She weighed fifty kg. She was beautiful and loved to flaunt her gold bangles, necklace and ring whenever an occasion arose. An avid reader—she would read the Hindi newspaper from cover to cover—although she was educated only up to primary school. In addition, Hindi movies would attract her. She would often go to the local Vasant talkies to watch a movie. In 1966, I saw Dev Anand’s “Guide” with her in this theatre—in the lady’s compartment! In Guntur she would ask the driver to take her to the theatre that was showing the 1975 blockbuster Sholay. She must have seen the movie at least three times. She even gave her granddaughters nicknames—Padmini and Helen!

She sang bhajans well and also remembered the Hindi song “सजन रे झूट मत बोलो” (Teesri Kasam, 1966 Hindi movie) so well. When Priti got married in Yavatmal on 13 February 2005, people couldn’t believe their eyes when they saw Bai singing this song on the stage!

In the evening of her life, memory failed her. So, whenever she would hear a bhajan on TV, she would clap and sing the bhajan.

Leaving behind a legacy

In January 2000, she had her will made. Badibai and Jiji and I explained to her page-by-page, and word-by-word everything that went into her will. She could understand all the intricacies and was fully satisfied with the way her assets were equitably distributed. I was pleasantly surprised to see my 75-year-old mother grasping accurately who was to get what, why, when and how much. Tapdiyaji was equally amazed—he played a dual role of a chartered accountant and a friend-philosopher-and guide to the family.

Anecdotes

“Did our parents ever fight?” I asked Asha, my Bhopal-based 80-year-old sister. She has elephantine memory, remembering every event and date, with remarkable accuracy. “All through their marital life of 46 years, I never saw Bai and Bhaiji fighting, except once. In 1977, Bhaiji was working at Bachhraj factories, Nagpur. I was also with them. Bai picked up an argument with Bhaiji— she wanted him to transfer all rights of Jaishree Bhavan (our Wardha home) to her. Bhaiji tried his best to persuade her that he won’t be able to fulfil this demand because of logistic, legal and tax issues. Amit was also with me. Bhaiji asked me to drop Amit to Bhopal and come back again. I returned the next day to Nagpur. It took us two days to convince Bai why her demand was unjust and impractical. Bhaiji also assured her that he would ensure that she would have enough money to fulfil all her wishes during her life. Finally, after two days of fasting, crying and silently seething, Bai agreed. The fight was amicably resolved. She suddenly became aware of insecurity, the reason she was so persistent,” Badibai could recall the incident almost hour-by hour.

Bhaiji would always bring Saris for her and daughters and stainless steel kitchen utensils or burtans from Mumbai. He also bought a Godrej steel almirah in sixties for Rs 300. ” You pay me whatever you wish,” said Wasudeoji Saraf when he went to buy the almirah. He had Rs 300 in his pocket and the deal was settled. That 61-year-old almirah is still with us— it requires six people to transfer it from a room to another. The 2-door steel almirah, its locker and drawers work as smoothly today as they did sixty years ago.

Says Anand, “I think I owe my laughter to Naniji. When I was with her in Wardha, she would repeatedly say, “आनंद हँस!” I am also as happy she ever was, because like her, I too do not remember the past. In her later years, at times she would fail to recognize me, asking me who was I. A little later, much to my dismay she would say my name Anand Singhi in full.”

Naniji was so active and agile. The minute guests came to our home to see her—they almost always dropped by unannounced—she would quickly go to her room and within a few seconds—not even minutes— she would change her Sari and bangles. She would welcome them, treating them with tea or snacks. And no sooner did the guest leave than, she would get back into the household attire. Her speed had to be seen to be believed. Modern girls need to learn this skill from Bai!

For her, lipstick was ओंठ पॉलिश. She would often ask me to apply lipstick. Whenever she found my lips without lipstick, she would ask me why I didn’t apply the lipstick.

When she turned sixty, SP mama told her to leave the chullah. “But I need to make at least a Phulka,” she said. “I will make Phulkas,” said SP mama and he did. This was SP mama’s birthday gift to Naniji.

Naniji’s great grandson was six-months old when she came to Bhopal. Mummy, Pratiksha and I too were with her. Bhopal is known to have steep hilly roads. We thought that given her age and heart condition, it would be difficult for Naniji to walk on the roads. She proved us wrong. She was always ahead of us, and walked briskly on the roads, without huffing or puffing.

Naniji used to laugh, heartily. When Pratiksha was six-months old, she looked at her and said, ” तेरे भी दांत नहीं, मेरे भी दांत नहीं!” Then she broke into an uncontrollable laughter.

Once I was going to Kochi. Naniji came to the Wardha East station with a pair of cotton pillows. She had asked me if I needed anything during my travel and I casually said that a pair of pillows could greatly comfort me. She immediately got the pillows made and handed them to me during the two-minute stop at the station, wishing me a comfortable journey and asking me to take care of myself while I was on the train. Such was her love and affection for me.

She had a special name for her granddaughters. I was Maharani; Mamta was Padmini and Maya was Helen! I was the first girl in the family to go to a convent school. When I was six, I came to Wardha for my summer holidays. I had recited “Twinkle little star; How I wonder what you are,” to the family. Naniji was so impressed with a six-year-old girl singing an English rhyme, that whenever anybody would drop in, she would immediately summon me and ask me to sing the poem. I have lost count how many times I did so. And she was not only all eyes and ears to me during the poem recital, but her face would beam with joy and a sense of pride.

Weddings in the Family

Whenever it came to finalising matches, she insisted—and Bhaiji ensured—that she was consulted and involved in the entire process—fixing a match, engagement, and wedding. Bai was witness to several births and weddings in the family— Kalantri, Singhi and Chandak. Many were born and married after she left this world. Many more shall get married in future. Here is a list of the birthdays and weddings of her sons, daughters, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. To see the list, please click here…

The Fateful Day

On December 5, 2005, an hour after she had eaten her lunch, Bai developed breathing difficulty. She was in Jaishree Bhavan. Kanata Bhabhi called me. I drove my Maruti 800 from Sevagram to Jaishree Bhavan. She had difficulty describing her symptoms but she didn’t look well. She vomited twice before me. I decided to take her to Sevagram Hospital. Kanta Bhabhi accompanied me. We admitted her to what was then an old Medicine ICU. Dr OP Gupta and Ulhas Jajoo saw her. The ECG showed changes of an old heart attack. Her heart was beating a bit slower.

Few hours passed by. At 9 pm, I thought that she would feel better in the familiar environment of my home. I used to live in a ground-floor flat in Vivekanand Colony in the medical college campus then. The home was just two minutes’ drive from the hospital. She said no to dinner and slept.

At 4 am, she looked and sounded sick. Kanta Bhabhi could sense that she was about to pass away. She asked her to recite a Bhajan and she recited: ” Sitaram Sitaram” and breathed her last. We got her off the bed and let her breathe her last on my lap. It was such a serene and peaceful death. We chose not to take her to the ICU. We didn’t make any attempt to resuscitate her, either. On December 6, 2005, she passed away in my lap in Sevagram home in the early hours of morning. She left the world as peacefully, and as quickly as Bhaiji did.

Badibai was in Indore, As soon as she heard the sad news, she asked Aalok to take her to Wardha. Aalok ensured that she reached by 1 pm. We performed her final rites at 4 pm.

This was our Bai. She nicely balanced tradition with modernity, faith with reason, and handled pleasures and pains. She belonged to an era in which women worked incessantly for their families without ever wanting to get their contribution acknowledged. “No mother is all good or all bad, all laughing or all serious, all loving or all angry. Motherhood is not a one-size-fits-all,” so wrote Erma Bombeck in her book, Motherhood: the Second Oldest Profession. True. Bai also kept on evolving—displaying her emotions that would so frequently change: being happy, sad, sarcastic, angry, arrogant, depressed, jubilant, lonely, loving, and generous. In the early days she endured pain, travail, and stress that tested all mothers those days; there was also an element of joy, happiness, and a sense of fulfilment in her life.

“All you who sleep tonight,

VIKRAM SETH

Far from the ones you love

No hand to left or right,

And emptiness above.

Know that you aren’t alone,

The whole world shares your tears

Some for two nights or one,

And some for all their years.”