We all fondly addressed him as Bhaiji, a term deeply rooted in the Marwadi language that is used to convey reverence and respect when referring to one’s father.

My father overcame a difficult childhood to build a successful life. A man who lived a full and meaningful life, he was a survivor, an entrepreneur, a family man, and a friend to many. Let me describe his story. Story of grit and persistence. Restlessness and resilience. Failure and success.

*****

From Taroda to Wardha: The Journey Begins

My father was born on June 19, 1916, in Taroda, a village located in Arvi Taluka of Wardha district. Our family’s exact origin is nebulous. However, like most Marwaris, our lineage can be traced back to Rajasthan, specifically to Phalodi, a town in the Jodhpur district. Unfortunately, little is known about his early life, except that he lost his parents to an infectious disease when he was only five years old. Since he was born so long ago, there are very few records of his early years, with no photographs in family albums, no papers yellowed with age, nor stories passed down through generations.

Nothing is known about his parents, uncles, aunts, and grandparents. He had four sisters: Godavari Gandhi (Tishti; 1910-1975), Dhapubai Rathi (Yelakeli; 1914-1978), Jankibai Rathi (Kharangana-Morangana; 1915-1981), and Kashibai Rathi (Nagpur; 1920-2007); and an elder brother, Nathmal (Taroda-Pimpalkhuta; 1912-1966).

Growing up as an orphan in abject penury must have been an incredibly difficult experience. However, my father never spoke about the hardships he faced, the agony he suffered, or the difficulties he endured. During his early years, he stayed with his sister in Kharangana-Morangana, 20 km from Wardha. Her husband, Bhivrajji Rathi, had migrated from Borgaon Saoli village (3 km from Anji) to Kharangana in 1920, where he built a home that still stands today. Bhaiji spent ten years living with his sister, waking up at 4 am to bathe in the cold river during winter, doing household chores, working for ten hours in the fields, and tending to the livestock. He left school after the seventh standard and returned to his native village, unsure about what to do next. Perhaps he felt that a small village like Taroda was not the place to make a fortune and grew tired of his mundane life, which led him to try his luck in Wardha. Although he was younger than his brother, they were exceptionally close. However, his brother lacked the drive and ambition to leave the village and chose to stay back, starting a petty shop, launching a business of moneylending, and looking after agriculture.

*****

Tryst with Bachhraj

The Bajaj group had its base in Wardha town during that time. In 1905, Rai Bahadur Seth Bachhraj Bajaj, a self-made moneylender and trader from Sikar, established a cotton ginning factory in Wardha. Unfortunately, his adopted son Ramdhandas passed away soon after his marriage to Vasantidevi. Bachhraj then adopted Jamnalal, who was only five years old at the time. When Bachhraj passed away, Jamnalal was just 17 years old. However, he went on to set up Bachhraj and Company Private Limited on 27 August 1926, built and inaugurated the Laxmi Narayan Mandir for Harijans on 17 July 1928, and launched Jamnalal Sons Pvt Ltd on 5 March 1938. Jamnalal inherited and expanded a flourishing cotton and money-lending business in Wardha. Despite not being well-educated, he was intelligent and shrewd when it came to managing his businesses, regularly visiting cotton markets to stay connected and informed. He was also a beloved associate of Mahatma Gandhi, who regarded Jamnalal as his fifth son. Jamnalal grew into an indefatigable social reformer, patriot, freedom fighter, and industrialist whose life and legacy continue to inspire people even today.

Life is full of surprises, and whether or not you believe in destiny or a higher power, it’s not uncommon for a stranger, someone you’ve never met before, to unexpectedly reach out and lend a helping hand as you navigate the challenges of life.

Association with Shri Chiranjilalji Badjate

Shri Chiranjilalji Badjate (1895-1973) played a crucial role in my father’s life as an angel in disguise. He was the managing trustee of the Jamnalal Seva Trust and the Laxminarayan Mandir, and also served as a Munim with the Bajaj

Group, taking care of Bachhraj Kheti.

In 1932, Chiranjilalji visited Taroda village and spotted my 16-year-old father chasing after the grazing cattle. He noticed something in his eyes and brought him to Jamnalalji Bajaj, advising him not to refuse any task that Jamnalalji would assign him. When Jamnalalji asked my father if he would willingly clean the toilet, he didn’t hesitate to say yes. Jamnalalji was testing to see if the boy was willing to work or not. This became an acid test that he used before hiring anyone for his office.

हमें चाहिए ऐसा नर, जो हो पीर, बावर्ची, भिश्ती, खर.

My father shared a deep bond with Chiranjilalji Badjate. In 1948, he played a crucial role in establishing a charitable trust named after Chiranjilalji’s mother, Sagunabai Badjate. Despite the trust’s dissolution due to financial constraints, their association endured, and they remained close friends and business associates. My father was grateful for Chiranjilalji’s mentorship and considered him a lifelong inspiration. In 1964, my father became a trustee of the merged Badjate Trust, alongside Chiranjilalji and other esteemed individuals, representing diverse backgrounds and perspectives. He was the sole non-Jain trustee in Chiranjilalji Badjate’s family trust, appointed alongside Advocate Moreshwar Purekar.

*****

The Determined Apprentice: Willing to Learn and Work Hard

So, his story had humble beginnings, but it all started on that fateful day when luck dealt him the cards that led him to Jamnalalji Bajaj. Fate had him end up in Gandhi Chowk, and he eagerly joined the Bajaj Group. He was only paid Rs 11 per month. He learned to live in Chowka in the office, where he ate his meals, washed himself, and slept at night. It was not an easy start, but he was willing to do whatever it took to succeed.

He started out as a jack-of-all-trades, doing whatever he was asked and running errands. He quickly impressed his superiors with his willingness to work hard and his attention to detail. He was also a quick learner, and he soon mastered the financial side of the business. Under the guidance of Chiranjilalji Badjate, he learned how to keep the accounts up to date, make clean entries, and developed an eye for detail.

My father had a staggering devotion to numbers. He could always spot any manipulated or misfitting numbers in the accounts. He had a keen eye for detail and a photographic memory. He was also a quick learner and was able to master the complex “parta” system of financial control within a short period of time.

Account books and ledgers became the essence of his professional life. He took great pride in his work and always made sure that the accounts were accurate and up-to-date. He was a stickler for detail and would often go back and check his work several times to make sure that it was perfect.

He learned the adage from Chiranjilalji, “whatever happens, the accounts must be in order.” He believed that this was essential for the smooth running of any business. He was also aware that accurate financial records were essential for making sound business decisions.

He acquired meticulous knowledge of accounts, particularly the “parta,” a centuries-old traditional Marwari system of monitoring and financial control. He took to the business like a duck to water. From then on, his success story sounded like an exaggerated fairy tale, but in reality, it was the result of tremendous hard work and brainpower.

*****

A Discovery

On November 30, 2022, I had the opportunity to visit my father’s office at Gandhi Chowk in Wardha, where he dedicated four decades of his career. It was a nostalgic journey for me as I sought to uncover information about my father’s early days. During my visit, I met Mr. Ambika Prasad Tiwari, who had been my father’s colleague in the same office since 1968 until my father’s untimely passing.

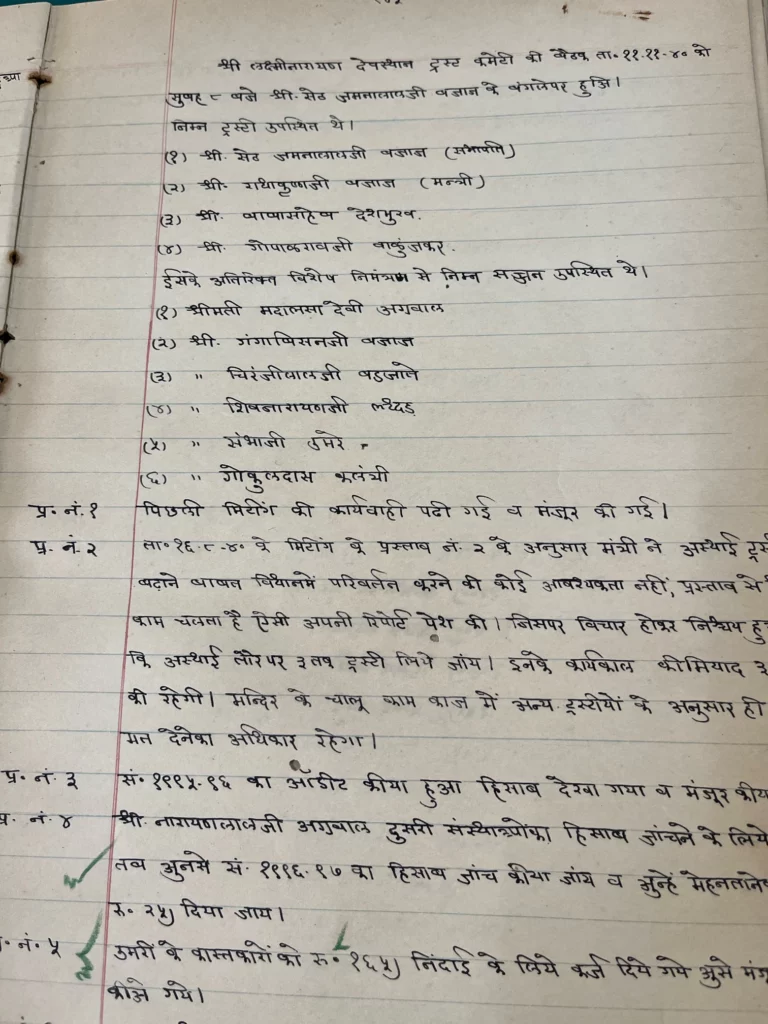

With Mr. Tiwari’s guidance, we embarked on a search through the office files, hoping to unearth some significant records. To our amazement, we stumbled upon an entry that marked my father’s presence as a special invitee to the Shri Laxmi Narayan Devasthan Trust meeting on November 11, 1940. This remarkable gathering had taken place at Jamnalalji Bajaj’s bungalow.

Reflecting on my father’s journey, I realized that he had started at the bottom rung of the ladder when he was first hired. It took him eight years of hard work, dedication, and perseverance to gradually ascend the ranks. The path to success had not been easy, but my father’s determination propelled him forward.

With the gracious permission of Mr. Tiwari, I obtained a copy of the minutes of the meeting from that significant day. The document held immense historical value, as it bore the signatures of influential figures such as Jamnalalji Bajaj himself. The minutes chronicled the attendance of esteemed members, including Shri Jamnalalji Bajaj, Radhakrishnaji Bajaj, Babasaheb Deshmukh, and Gopalrao Walunjkar as well as special invitees like Mrs. Madalsa Narayan, Chiranjilalji Badjate, Shivnarayan Laddhad, Sambhaji Umre, and, of course, my father.

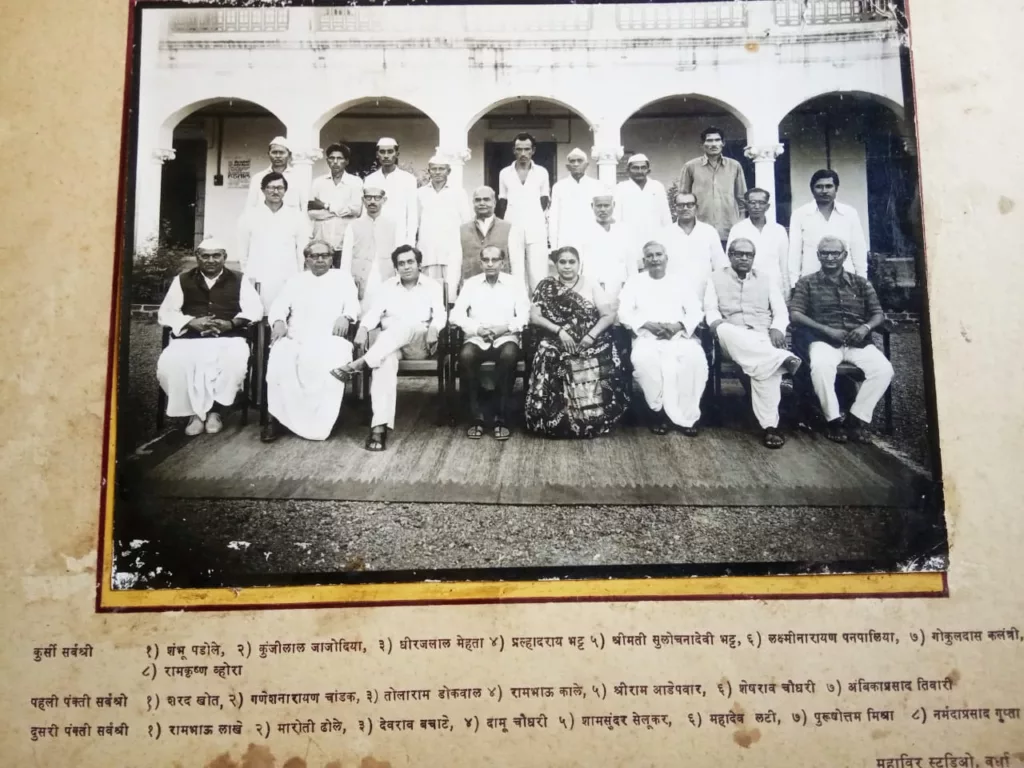

Over the span of 46 years, my father worked for four different parts of the Bajaj group: Jamnalal Sons Private Limited, Bachhraj Factories Private Limited, Jamnalal Bajaj Seva Trust, and Shri Laxminarayan Devasthan Trust. In his early days, he looked after close to 100 acres of land that Bajaj Group owned in Jamani village, 15 km north of Wardha, near Sukli, before moving to Bachhraj factory. His office was located in Gandhi Chowk, near the Durga Talkies theatre. His colleagues included Ganeshnarayanji Chandak, Shambhuji Padole, Govind Narayan Bajaj, Rambhau Kale, Devrao Gawande, Shriram Adepawar, Maniklal Chhangani, Sharad Khot, and Purushottam Mishra, as recalled by Ambika Prasad Tiwari.

In addition to his work with the Bajaj group, my father also managed the Laxmi Narayan Mandir, which was overseen by the Shri Laxminarayan Devasthan Trust. When Shambhuji Padole stepped down in August 1986, my father became the secretary of the Jamnalal Bajaj Seva Trust. He held this position until his passing four months later.

My father had a knack for adapting to new situations, recognizing opportunities, and making the most of them. As a result, he became one of the most respected members of the Wardha community. While I’m not certain about his specific roles, I do remember that during my school years, he managed the local cotton and ginning unit owned by the Bajaj group, known as Bachhraj Factories.

*****

Marriage

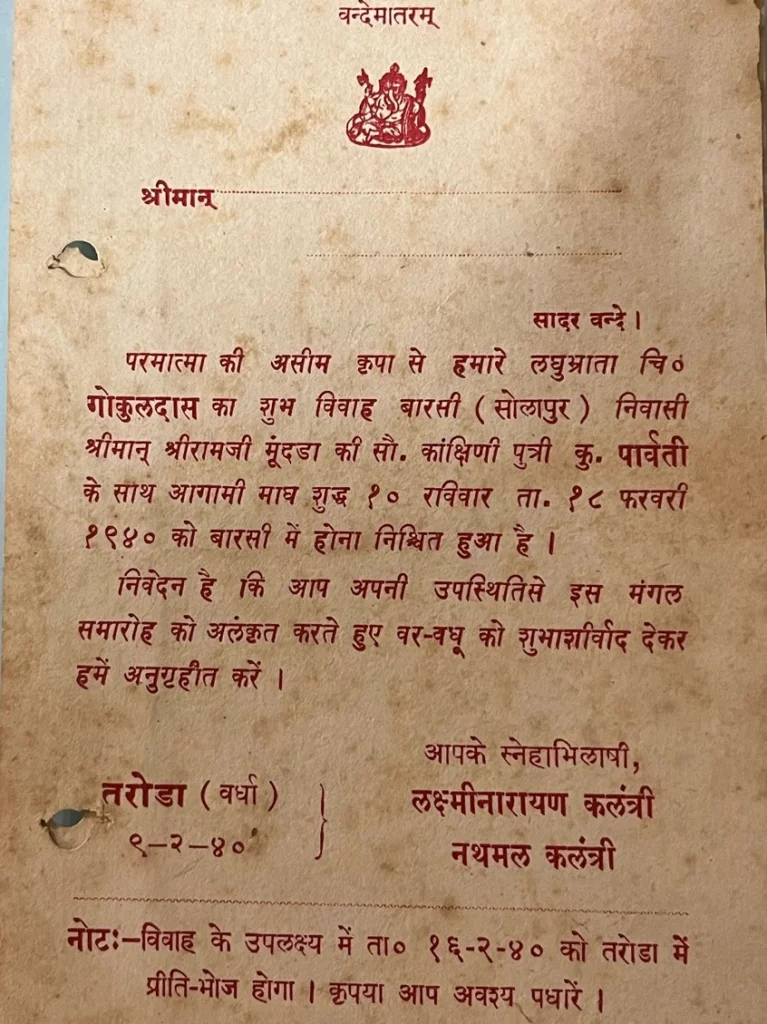

On the 18th of February 1940, my father and Parvati exchanged vows and were joined in marriage. Parvati, who originated from Barshi town in the Solapur district of Western Maharashtra, became my mother. I often wonder how my Nanaji agreed for this marriage when it would take a staggering 48 hours to travel from Barshi to Wardha. And they had to change trains at Kurduwadi, Daund, Manmad and Bhusawal stations before they reached Wardha. Today, the car ride from Wardha to Barshi takes just eight hours. My mother, who had completed her education up to the fourth standard, was merely 15 years old when she tied the knot with my father.

It was 1940, and India was still struggling under British rule. My Nanaji was a devout temple-goer, faithfully attending the early morning Kakda Aarti at 4 am. When my father expressed a condition for their marriage, they were taken aback. “I insist that the bride does not wear a ghoonghat throughout the wedding ceremony. I also request that her face remains unveiled when she arrives in Wardha,” my father firmly and resolutely declared.

My Nanaji and Naniji, accompanied by their elders, were at a loss for words upon hearing my father’s condition. The idea of a bride without a ghoonghat seemed unfathomable in their society, especially during the wedding ceremony. “How can you accept a boy with a dark complexion, no parents, no roots, no proper shelter, and who wants Parvati to unveil her head? How will my daughter adjust to the boy of your choosing, who lives 500 miles away?” Naniji voiced her understandable confusion to Nanaji. However, my father’s condition prevailed, marking a groundbreaking moment in the Marwari community in Barshi—the first wedding where the bride did not don a ghoonghat.

In the year 1940, in India, amidst a society deeply entrenched in orthodox traditions and rituals, my father’s actions stood in defiance of societal norms. This act of defiance unfolded in a community where every ritual was meticulously upheld.

What motivated this young man to defy age-old traditions and advocate for a wedding without veiling the bride’s face? His conviction grew stronger after witnessing Jankidevi Bajaj, the wife of Jamnalalji Bajaj, the owner of Bajaj Group, personally discarding the practice of Parda and actively campaigning against it in the Marwadi community.

In October 1933, Mahatma Gandhi himself wrote a passionate letter urging women at the Marwadi Mahila Sammelan in Kolkata to refrain from covering their faces with veils.

Between 1928 and 1935, Kaka Kalelkar held the position of vice chancellor at Gujarat Vidyapeeth. During his tenure, he introduced a revolutionary Vedic ritual that condensed the entire Hindu marriage ceremony to just 40 minutes, drawing inspiration from the Vedas. Shri Jamnalal Bajaj was captivated by this new approach and eagerly embraced the change. Following Kaka Kalelkar’s lead, he also chose to forego the customary bridal veil during his daughter Kamla’s wedding to Rameshwar Prasad Nevatiya. Inspired by this progressive mindset, my father also adopted the practice of limiting baraatis to a maximum of 50 guests in our family weddings. Although my father chose to wear Khadi clothing for his own wedding, he respected my mother’s choice to wear what she felt comfortable in.

Additionally, he found inspiration in Chiranjilalji Badjate, who believed in breaking free from societal norms, including the custom of brides wearing ghoonghat. These influential figures and events emboldened my father to challenge prevailing customs and choose a path of his own. It is through such association and inspiration that my father found the strength to challenge prevailing customs and forge a path of his own.

I was able to find my parents’ wedding card in an old file. It was beautifully designed and worded, with no extra words. The language was simple, elegant, and in North-Indian Hindi, with “Vande Mataram” prominently displayed at the top of the card.

The enduring love and admiration between my parents remains etched in my memory to this day. Whenever my father returned from his annual meetings in Bombay, he would bring back gifts for the family: clothes, stainless steel utensils, and gold. On his cousin’s wedding day in 1955, he presented my mother with a remarkable gift of 80 tolas of gold. In turn, my mother always ensured that guests who visited our home were treated with utmost courtesy and provided with delicious meals, regardless of the time of day.

My father affectionately referred to my mother as “Asha Ki Bai,” while she addressed him as “Asha Ka Bhaiji,” as it was uncommon for couples to use their first names in those times. They conversed in Marwari, their mother tongue. Following the birth of my sister Asha in 1942, our household experienced a newfound financial prosperity. Bhaiji often remarked, “I owe my wealth to Asha,” acknowledging the positive impact she brought into our lives.

*****

Marwari Mohalla: Our first home

After tying the knot in the summer of 1940, my parents rented a house in Wardha town’s Marwari mohalla, now bustling with markets. The house, owned by Mr. Pipalwa. a brahmin, stood among neighbors like Mr. Murlidhar Saraf, Mr. Dwarkadas Saraf, Mr. Gowindram Saraf, Mr. Surajmal Belawala, Mr. Chaubey, Mr. Kanhayyalal Tibdewal, Mr. Satyanarayan Goenka, Mr. Durgadas Gandhi, Mr. Nare, and Mr. Bagda. Despite local tales of haunting spirits surrounding the house, my father, dismissing such superstitions with disdain, boldly proceeded to rent it.

For fifteen years, they called that place home. During this time, my mother gave birth to five children, comprising two girls and three boys. In 1955, my father could finally afford an LPG stove, but my mother, accustomed to the rustic charm of the smoke-emitting chullah, promptly returned the modern appliance along with the gas connection. Those were the days when my mother efficiently managed a bustling household without the aid of cookers, mixers, grinders, refrigerators, microwaves, cooking ranges, telephones, or electricity. Remarkably, she never seemed to encounter any issues or voice complaints, no matter what challenges arose.

*****

Bajaj Electricals Campus: Our Second Home

Around 1955, my father secured a rental home on the Bajaj Electricals campus, situated near Gandhi Chowk. Bajaj Electricals, originally known as Radio Lamp Works Limited when it was incorporated on July 14, 1938, underwent a name change to Bajaj Electricals Limited on October 1, 1960. Our new residence, just half a mile away from our previous one, belonged to the esteemed Bajaj group. It was within these walls that I came into the world, born at home on August 15, 1957. Notably, this was also the place where my elder sister Asha’s wedding ceremony took place.

Our neighbors included Sundarlal Bhutada, along with his sons Champalal, Kanhaiyalal, Mohan, Madan, and his daughter. Despite being a rented house, my father took the initiative to construct a toilet, considered a luxury at that time. Right in front of our home, Shri Vallabh Rathi, a B.Com student, resided. Known for his strict discipline, my father would rouse him and his friends at five o’clock in the morning, encouraging them to go for long walks or engage in a game of football.

In the evenings, we welcomed select visitors to our home, including Dr. Gholap, Professor RK Vora, Mr. Kabra, and Gowardhandasji Jajodia. Their presence filled the air with lively interactions and laughter, creating a joyous atmosphere.

Our family, inspired by the ideals of Jamnalalji Bajaj, also took on the responsibility of caring for cows. When my father joined the Bajaj Group, he wholeheartedly embraced the task of looking after these animals. The year 1941 marked a significant turning point when Jamnalalji Bajaj made the life-changing decision to dedicate himself to the service of cows. He founded the Go Seva Sangh, a society focused on their welfare, and Mahatma Gandhi inaugurated it in September of the same year. Shortly before his passing in February 1942, Jamnalalji relocated to Gopuri, where he resided in a small hut alongside the cows. He diligently tended to their needs, providing them with nourishment, and engaging in insightful conversations with knowledgeable individuals on ways to enhance their well-being. In his early thirties, my father was entrusted with the responsibility of being a trustee in a cow welfare trust established by Chiranjilalji Badjate. These profound experiences greatly influenced my father’s decision to make cows an integral part of our family and to prioritize their care and well-being.

One of our cows gave birth to a calf, whom we affectionately named Shankar. Interestingly, there was an office peon who coincidentally shared the same name—Shankar. Every day at 3 PM, he would prepare tea, ring a bell, and loudly call out, “Shankar, come out.” At the tender age of three, I eagerly awaited this daily ritual. Sneaking under the grill gate, I would indulge in the sugar that Shankar offered, much to my mother’s disapproval. It was a delightful secret treat that I couldn’t resist.

*****

Bachhraj Press and Ginning Factory: Our Third Home

In 1961, we relocated to a house within the Bachhraj Factories compound, where my father worked. We resided there until 1965. Situated at Bajaj Square, it was a short distance from our previous home. In May 1965, my sister Pushpa had her wedding ceremony in this house. I attended Cradock High School, which was later renamed Mahatma Gandhi Vidyalaya, from 1965 to 1968 while residing in this home.

*****

Jaishree Bhavan: Our father’s fourth and final home

In 1967, at the age of ten, my family relocated to a magnificent mansion named Jaishree Bhavan. The story behind this home is quite fascinating.

My father had always dreamed of owning a big house, and once he was financially stable, he began searching for one. In April 1965, a broker in Wardha informed him that a large, spacious bungalow was up for sale.

How did this school come into being? The Marathi medium school was founded by Laxmibai Purushottam Kelkar in 1936. The school was named after Kesarimal Sharma, a wealthy businessman from Wardha who gave substantial donations to build the school. Vatsala, Lakshmi’s younger daughter, wanted to go to a school but there were no girls’ schools at Wardha then. Lakshmi realized that it affected not only her own daughter but numerous other girls who were keen to study. Lakshmi’s untiring efforts resulted in laying the foundation of the first girls’ school at Wardha , now known as ‘Kesarimal Girls School’. She searched for dedicated teachers and arranged their accommodation in her own house. Venutai Kalamkar and Kalinditai Patankar were the first teachers of the school; they paved the way for women literacy at Wardha.

Jaishree Bhavan, our fourth residence, was originally built by Dr. Tukarampant Kedar in 1910, on Bachelor Road, Wardha. This two-story bungalow boasted a large central hall, rooms on either side, a substantial basement, and a verandah that overlooked the garden. Constructed using brick and stone, it featured a sloping roof, thick walls, high ceilings, and a deep porch, all reflecting the British architectural style of the time. The bungalow spanned 4,200 square feet and occupied a generous plot of 28,500 square feet, presenting a modest whitewashed exterior.

Following Dr. Kedar’s passing in 1951, his son Mukund inherited the property. Mukund, a judge who commuted to the Wardha court on horseback, resided there. The bungalow neighbored Mr. Lule’s residence to the south and the Jain boarding house to the west. In 1936, Mukund leased the bungalow to Kesarimal Kanya Shala, which operated as a school for 33 years.

*****

Overcoming Challenges and Securing Possession: A Strategic Journey

In June 1965, my father purchased the bungalow from Mukund for Rs 41,000, marking it as our family’s fourth home, Jaishree Bhavan. The next challenge was to gain complete possession of the property. Despite warnings from acquaintances that it would be an arduous task to evict the school, which was overseen by a society consisting of influential lawyers from Wardha, my father remained resolute in his determination.

Advocate Nagle, the president of the school society, was unaware of my father’s intentions when my father began visiting him every morning for tea and conversation. After a month, Advocate Nagle inquired about the purpose of these visits. My father explained that he wished to move into the bungalow he had acquired but couldn’t do so until the school found a new location.

To expedite the process, Mr Nagle suggested that my father make a donation of Rs 5,000 to the school. The following day, my father intentionally wrote a cheque for Rs 7,000 and entrusted my brother, Om, to deliver it to Mr Nagle. Upon seeing the unexpected amount, Mr Nagle was astonished and promptly contacted my father to express his gratitude for surpassing their expectations. My father downplayed the situation, claiming it was merely a mistake in the cheque amount, but he had a plan behind his actions. He confided in us later, saying, “This cheque will help me secure what I desire the most – clear possession of the property.”

The school management committee, enticed by the larger donation, fell for the ruse and vacated the premises, granting my father the rightful possession of the property. His strategic approach had proven successful in achieving his goal.

The news that my father had bought the property at a bargain price spread quickly in town. People began to frequent Mr. Kedar’s home, offering him as much as twice the amount my father had paid. However, Mr. Kedar, a man of principle, remained steadfast and resisted these tempting propositions. He explained to my father during their lunch, “In the world of Marwaris and Banias, the word for trust is Saakh, which is closely tied to honor. It is the foundation of creditworthiness and business integrity, holding far greater value than mere wealth. Today, I wanted to reaffirm the significance of Saakh.” After their meal, he added, “I have learned from my father the importance of always keeping your word. It should not be given lightly, but once given, it must not be broken. Like Marwaris, we should strive to honor our agreements and avoid any act of betrayal.”

Shortly thereafter, my father received a disheartening notice from the office of the Wardha collector, Mr. DN Kapoor, stating that the government intended to acquire his property. Feeling upset and frustrated, he decided to personally visit the collector, whom he knew through Kamalnayanji Bajaj’s election assignments. Expressing his dismay, my father shared how the notice had caught him completely off guard. To his surprise, the collector proposed a clever plan to outsmart the government’s acquisition efforts. “Print the invitation for your housewarming ceremony and make sure it reaches my desk. While I may not attend the event, I will take action based on your letter. I will assume that the property is already occupied, and the government would prefer not to displace the current occupant,” the collector suggested, offering a viable solution.

*****

Converting the School into a Home: Redefining the Space

In 1967, we settled into our current residence. Once my father had obtained complete ownership of the property, he envisioned transforming the former school into a comfortable home for our family. In 1970, he sought the assistance of Mr. Shamlal Baiswar, an engineer who operated Bihari Mechanical Works in Wardha, to approach Mr. Sheodanmal, a renowned architect from Nagpur and a recipient of the Padmashree award. Their objective was to request a redesign of our house.

During Mr. Sheodanmal’s brief visit to our home in Wardha, he spent only half an hour inspecting the premises before departing. This left my mother somewhat disappointed, as she had hoped for a more in-depth discussion of the architect’s plans with the family. However, to our surprise, just a week later, Mr. Sheodanmal sent us a collection of half a dozen drawings. After carefully reviewing the plans and ensuring they aligned with our family’s needs, my father commenced the construction work.

Mr. Baiswar, along with my father and brother Om, dedicated their efforts tirelessly to bring the architect’s plan to life. They made numerous visits to the architect’s office in Nagpur, collaborating closely on the execution of the project. My father possessed a keen eye for detail and a strong sense of precision. He knew precisely what he desired and how to achieve it. Even my mother and father joined in the process of “curing” the walls, which involved wetting the newly constructed brick walls to ensure optimal bonding between the bricks and cement, strengthening the walls and preventing cracks. Additionally, my father hired a skilled 16-year-old boy to meticulously lay the floor tiles, resulting in a flawless alignment. Remarkably, over five decades have passed since then, and the tiles remain as pristine as the day they were laid.

In addition to the meticulous design and construction, my father paid great attention to the details of the house. He ensured that the toilets were spacious and incorporated the installation of exhaust fans in two of them. One of the most striking features of the building was a 10-foot-long porch supported by cantilevers, giving it a distinctive film studio appearance.

For the painting work, my father hired Janrao Shende, a local painter who also had skills as a plumber and electrician. When the painting was completed in 1972, Mr. Sheodanmal, the architect, revisited the house to inspect it closely. He was highly impressed by the quality of the painting and inquired about the painter and the cost. To everyone’s surprise, my father revealed that Janrao Shende had painted the entire house in exchange for just a bag of wheat and Rs. 250! It was a testament to the exceptional talent and affordability of Janrao, who had delivered remarkable results within a modest budget.

Jaishree Bhavan, our beloved family home, derived its name from the combination of my father’s two younger sons, Jaiprakash and Shriprakash. Interestingly, neither of them resided in this home permanently; instead, it became the residence of my eldest brother, Ashok.

Soon after Ashok’s marriage, my father and his nephew, Uttamchand, had disagreements regarding the property. After several stormy meetings, they decided to divide their assets in May 1969. As part of the partition, Uttamchand was allocated 8,000 sq ft of the total 28,650 sq ft plot of Jaishree Bhavan. Additionally, he also received full ownership rights in another plot, the Empress Mill layout, which was initially purchased jointly by my father and Mr. Vinayakrao Bhise. Meanwhile, my father retained the remaining 20,650 sq ft plot, ensuring a fair distribution of assets between the family members.

*****

The Office at Gandhi Chowk

My father possessed a natural talent for finance, although I’m uncertain of his exact position within the company. He maintained a meticulously organized office at Gandhi Chowk, meticulously managing separate accounts for each business class, recording trade bills, inventory records, and keeping a cashbook. He was well-versed in the Marwari Accounting system, one of the oldest cost management accounting systems.

He was a staunch advocate for a performance-based pay structure, firmly believing that it would motivate individuals to work harder and generate better returns for the company. Eventually, his management recognized the benefits and agreed to grant him a share in the firm’s profits.

Each day, my father would walk to his office situated near Laxmi Narayan Mandir and Durga Talkies in the vast Gandhi Chowk area. His office was simple yet dignified, with a grand mattress and large, thick, bullet-shaped pillows covered in pristine white Khadi sheets. He led a dedicated team, including supervisors, accountants, cashiers, and managers. He had a dedicated team working with him, including Shambhuji Padole as the Supervisor of Jamnalal Sons, Ganesh Narayan Chandak as the Accountant, Govindram Bajaj as the Cashier, Shriram Adepawar as the Manager of Bachhraj Press, Gawande as the Manager of Bachhraj Ginning Factory, Ambika Prasad Tiwari as the Typist, Ratanlal Sultania, Sharad Khot as Typist, and Maniklal Chhangani as another Cashier. Unfortunately, we recently lost Deorao, who had been serving as a peon in the office.

During the 1960s and mid-1980s, our family had a landline phone with the straightforward number 333, while my father’s Bachhraj office boasted the prestigious single-digit number 8. The phone itself was a sturdy black instrument with a hefty handle that required lifting and holding against the ear. Ingeniously, my father installed a 30-foot extension wire, providing limited mobility within its range.

Every morning at 5 am, my father would dial Mr. Purushottamdasji Jhunjhunwala, the managing director in Bombay, to discuss the previous day’s business transactions. However, after 7 pm, he staunchly refused to take any calls, even from his superiors. He firmly believed in the right to a personal life and maintained clear boundaries.

Prior to my father taking over the Bachhraj factory, payments to cotton brokers would often extend past midnight. Recognizing the need for change, he implemented a new rule. He instructed the cashier to complete all financial transactions and lock up the Tijori (cashbox) by 6 pm. Initially, the brokers protested, but they soon realized the benefits of this practice. It allowed them to utilize their time more efficiently and effectively.

I have many cherished memories of my time at Craddock High School, which was conveniently situated between the ginning and pressing factory and our home. I had a wonderful group of friends, including Suhas Jajoo, Chandu Fattepuria, Avinash Bhagwat, Shekhar Deshkar, Santosh Kekre, Ravindra Vaidya, Ravindra Chawade, Narendra Gharpure, Vilas Thakur, and many more. We would often gather and spend hours climbing and playing on the cotton bales that were stacked around the area. It was a delightful experience, as we would playfully toss cotton at each other, almost like people playing in the snow. Those were joyful moments that I will always cherish.

*****

Facing Hostility: Envy and Resentment

In October 1968, a tragic incident occurred in our town. One of my father’s close associates at the Bachhraj factories took his own life on the first floor of the Gandhi Chowk. The entire city was in mourning following the passing of Tukdoji Maharaj on October 11, 1968. Amidst this atmosphere, my father’s colleague went missing, and his lifeless body was discovered two days later in a room on the building’s first floor.

Unfortunately, my father faced a wave of hostility and resentment from some individuals in the community. They were envious of his rapid success and directed their animosity towards him. Speculation and unanswered questions surrounding his colleague’s death fueled rumors and accusations, with some even pointing fingers at my father as responsible for the tragic event.

In an attempt to tarnish my father’s reputation, certain influential people from the city contacted Mr. Kamalnayan Bajaj in Mumbai. As the son of Jamnalalji Bajaj, the owner of the factory and Member of Parliament from Wardha, they tried to manipulate his perspective with fabricated stories. However, Mr. Bajaj displayed great integrity by refusing to entertain these accusations and steadfastly stood by my father’s side until he was vindicated of any wrongdoing.

My father grew very wary of the local community, which took a negative stand and distanced himself from the activities of the Mandal.

*****

Relocation and Responsibility: The Shift to Nadimpalem

In the early 1970s, the ginning and pressing factory in Amravati was dismantled and relocated to Nadimpalem, a village situated 21 km southwest of Guntur in Andhra Pradesh. This crucial task of managing the new factory was entrusted to my father, who embraced it with his characteristic boldness and adventurous spirit. Between 1974 and 1977, he assumed the role of leading the operations at this newly established unit.

My father had always been drawn to new challenges, eagerly seeking out opportunities to make a difference. When approached by the management and asked if he would be willing to take charge of the Nadimpalem factory, he didn’t hesitate to accept the responsibility. His reputation as a skilled turnaround specialist had preceded him, as he had successfully revitalized struggling factories in the past, consistently improving their financial performance.

The Nadimpalem factory, strategically located on the bustling Chennai-Vijayawada highway, held immense potential for growth and success. It presented my father with a fresh canvas on which he could employ his expertise and drive positive change.

Vijay Rathi, the 24-year-old son of Kamlabai Rathi from Wardha, had the opportunity to work alongside Bhaiji for two and a half years. During this time, Vijay took on various responsibilities such as purchasing cotton, managing accounts and cash, drafting business letters, and fixing minor machine errors. He got married on February 21, 1977, and even took his newlywed wife to the Guntur factory. Vijay fondly remembers the affordable dosas they would enjoy, costing only 35 paise at the time.

He recalls an incident when he attempted to book a telephone call to Amroha in Uttar Pradesh, his father-in-law’s place, and it took three days for the call to go through. Vijay used to accompany Bhaiji on a scooter for office-related work to and from Guntur. After enduring the sun, rain, and wind, Bhaiji eventually asked Vijay to write to Shri Purushottamdasji Jhunjhunwala, the Mumbai-based managing director, requesting a car. The request was approved, and Vijay was sent to Hyderabad to purchase an Ambassador car for Rs 22,000.

Vijay vividly remembers those days, as they had a significant impact on his life. He acknowledges Bhaiji’s influence in shaping his life and career, particularly in the areas of finance and administration. Vijay shared a message with me that listed the names of those who worked with my father at the Guntur factory, including Maruti Jain, Prakash Paliwal (Arvi), Kishorbhai Thakkar (Amravati), Gopiram Kanodia (Surajgarh), Vasanta Gakre (Electrician), Joshiji, Ambadas Bhai (Bhuj), and Paliwal (Dhamangaon).

Guntur. 12 July 1975. My father is second from right- in Dhoti and Kurta.

In November 1977, a devastating cyclone hit Andhra Pradesh, causing significant damage to the Bachhraj ginning and pressing factory in Nadimpalem. The storm was one of the worst to hit India since Independence, causing widespread destruction in the Krishna River delta region. The tidal wave that followed was over 6 meters high, 80 km broad, and 24 km deep, causing havoc in low-lying districts like Krishna, Guntur, Prakasam, and Nellore. The factory was badly damaged, and despite efforts to repair it, it was irreparably ruined. As a result, the family moved back to Nagpur.

*****

Bhaiji shared a special bond with Kamlabai Rathi, Vijay’s mother, whom he considered his Raakhi sister. Their friendship blossomed during their regular meetings at the Laxminarayan temple in the early 1960s when the Rathi family resided at the Bajaj Electricals campus. Over time, Kamlabai started treating Bhaiji like a brother, and their familial relationship deepened.

In December 1978, Vijay’s father decided to purchase a house near Shivaji Chowk from a teacher at New English High School. Bhaiji, upon seeing the old house, suggested that Vijay should dismantle it and construct a new one in its place. Initially hesitant, Vijay’s father eventually agreed, and the process of dismantling the old building began. To mark the beginning of the construction of the new building, a Bhoomi Poojan, or groundbreaking ceremony, was conducted by Bhaiji and Parmanandji Tapdiya.

*****

Return to Nagpur: Father’s Comeback (Early 1977)

The Nagpur unit of the Bachhraj factory was located near the present-day government bus stand, approximately one kilometre away from the Government Medical College. It was an old building with sloping roofs, thick walls, and a stone-paved floor. Between July 1973 and May 1974, while my father was serving in Wardha, I lived in a 10×10 room in the factory office while attending medical college. In early 1977, my father returned to Nagpur, but I chose to continue staying in the GMC hostels. He worked there for about a year before returning home and later starting a new chapter in Adilabad.

*****

Relocating to Adilabad: A New Chapter Begins

In 1983, Bachhraj management asked him to take over as the chief of the Adilabad unit of the Bachhraj factories, as the local manager had mismanaged the finances, resulting in the unit running in the red. My father readily agreed and moved from Wardha to Adilabad. He spent the last three years of his life dividing his time between Wardha, Nagpur, and Adilabad, which was located 150 km south of Wardha. His driver would drive him to Wardha almost every week, but neither my mother nor any of his sons went to Adilabad. In fact, my mother repeatedly urged him to stop nursing the sick units of Bachhraj factories and stay in Wardha instead. He was also given the responsibility of renovating the Bachhraj Dharamshalas in Wardha, and the final responsibility of selling the two sick units in Nagpur and Adilabad, but unfortunately, he passed away before accomplishing the task.

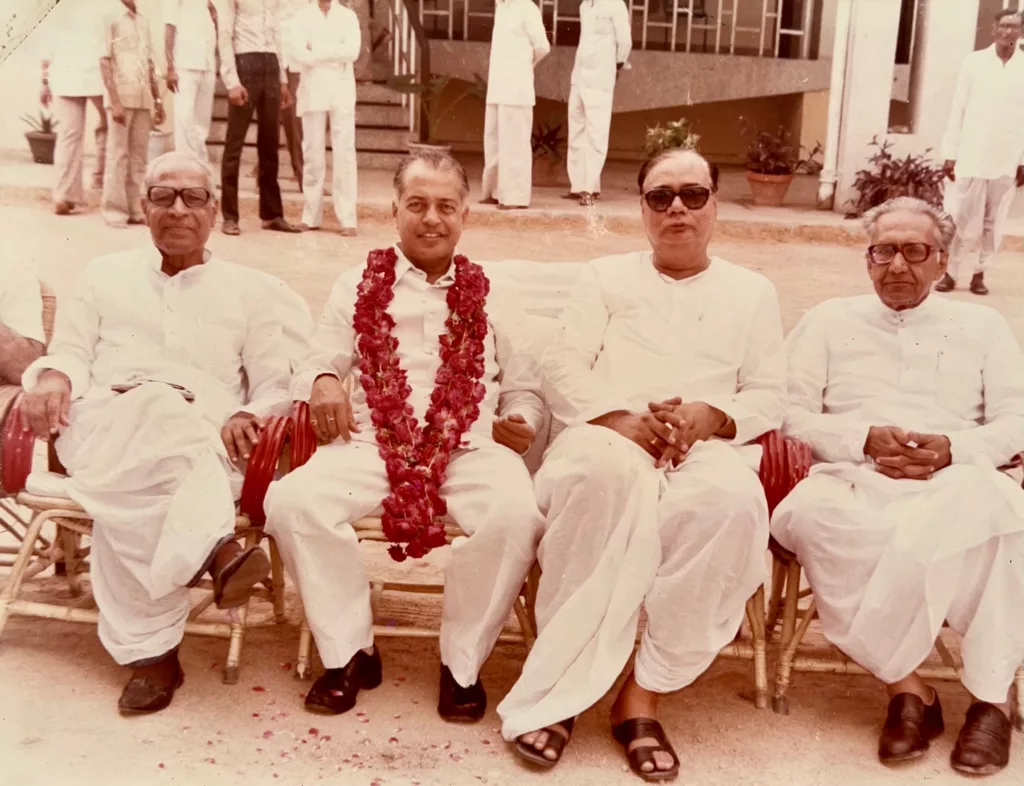

Bhaiji, Purushottamdasji Jhunjhunwala, Kashiprasad Dokwal, Kunjillaji Jajodia. Bachhraj Factory. Adilabad. 1985.

Partnership with Champalalji Fattepuria

During the early 1970s, Wardha was home to four prominent cotton firms: Bachhraj factories, Hiralal Pannalal represented by Champalalji Fattepuria, Narnoli, and Gulabrao Bhise. Despite being competitors in the industry, my father and Champalalji maintained a friendly and cordial personal relationship. They even attended regional and national conferences on cotton together, starting around 1965, including one at Hotel Asoka in Delhi.

My father played a crucial role in the establishment of the Wardha Cotton Market Association, where he served as the president, and Champalalji as the secretary. Additionally, he founded the Wardha Hajaar Vyapari Sangh, which provided a platform for cotton merchants to discuss professional matters.

However, the implementation of the government’s Monopoly Cotton Procurement Scheme on July 1, 1972, brought significant disruption to the cotton industry in Maharashtra. Private parties were no longer allowed to directly purchase cotton from farmers, as the Maharashtra State Co-Operative Federation became the sole buyer and seller of cotton.

Recognizing an opportunity in Pandhurna, Champalalji and my father formed the Paras Cotton Company. They rented local ginning and pressing mills and successfully sold up to 8,000 cotton bales at its peak. Their clients included prominent entities like Mafatlal Mills, the Piramal Group, and various vendors in Bombay. Mafatlal Mills made it a tradition to purchase cotton from them on auspicious occasions. However, despite initial success, the partnership faced financial losses, leading to its dissolution in 1984. Nonetheless, the friendship between my father and Champalalji remained strong.

*****

Yogendra Fattepuria recalls

“Gokuldasji was a rogressive thinker. I vividly recall how he encouraged my grandmother and the daughters-in-law at home to abandon the practice of ghunghat, the facial veiling of Hindu women. He believed in adapting to the changing times,” Yogendra Fattepuria shared.

“In 1976, during my cousin’s sister’s wedding, we faced a dilemma as all the dharamshalas were fully booked, and we couldn’t find a temporary venue for the ceremonies. Moreover, we needed accommodation for a large wedding procession from Jalna. When Gokuldasji learned about our predicament, he made us an unbelievable offer. He generously offered Jaishree Bhavan, his own spacious residence, and the newly constructed JP Sadan to accommodate the approximately 150 baraatis. He went a step further and arranged a delightful sit-down dinner for the baraatis. Gokuldasji’s incredible generosity and benevolenc defies adequate description.” recalled Yogendra Fattepuria.

“Gokuldasji had a passion for traveling. In 1972, he embarked on the Amarnath Yatra with his friends Champalalji Fattepuria, Satyanarayan Goenka, Satyanarayan Bajaj, Ratanlal Kela, Shriram Kathane, and Chenkaranji Fattepuria. They arranged three cars from Wardha and packed their suitcases with warm clothes, jackets, caps, and gloves. Additionally, he often accompanied Champalalji on post-Diwali visits to Shikharji, an important Jain pilgrimage site located on Parasnath Hill in Jharkhand,” he added.

“Who can forget the Friday Kachha Chiwda party? Gokuldasji, Champalal Fattepuria, Satyanarayanji Bajaj, Ratanlal Kela, Gopaldasji Rathi, Mohod, and others would gather to exchange gossip and enjoy a serving of Chiwda that cost no more than Rs two. The Kachha Chiwda became a catalyst that stimulated their conversations, fostered camaraderie among brokers and businessmen, and influenced their trading decisions.”

I remember hearing words like Varalakshmi, H-4, MCU-5, Nimbkar, 1007, and Laxmi constantly. Little did I realize then that these were the varieties of cotton produced in Maharashtra. My father was an expert in grading cotton, which is one of the most difficult and challenging tasks in the marketing of cotton.

Entrepreneurial Spirit: Venturing into the World of Business

From his experience of independently managing a household in Wardha, my father gained efficiency and worldly wisdom. This propelled him into the world of business, where he believed in strategically managing investment funds and closely monitoring finances for long-term productivity. He was a risk-taker, relying on intuition rather than rigid plans, which led to the establishment of numerous cloth shops in Vidarbha and Marathwada.

In 1963, he joined forces with Professor Ram Krishna Vora from Wardha to embark on a clothing retail venture with the ambitious goal of setting up 108 shops in Vidarbha and Marathwada. However, the partnership was short-lived and came to an end in 1968. From 1945 to 1980, he engaged in various businesses, including real estate investments, dairy farming, commodity trading, money lending, cloth shop operations, and cotton trading in places like Pandhurna, Adilabad (Andhra Pradesh), and Kolkata. He also collaborated with locals to purchase plots of land in Wardha.

My father demonstrated courage in making tough decisions and opposing anything that didn’t align with his conscience. He strategically invested in land and gold since stock exchanges and mutual funds were not available during that time. He made swift decisions and meticulously verified all the details. However, not all of his ventures proved successful, such as the Greenfield Chemoplast, a PVC pipe-manufacturing unit, which had to be shut down a few years after his passing due to financial difficulties and substantial debts. Nevertheless, finance ran in his veins, just as chivalry ran in the blood of the Rajputs!

*****

Challenging Conventions: Defying Traditions and Superstitions

My father was a progressive thinker who defied traditional norms and did not conform to societal expectations. He held little regard for rituals and traditions, often considering them insignificant. In 1965, when pundits suggested a specific auspicious time for my sister’s marriage ceremonies around midnight, he rejected the idea. Instead, he broke free from conventions and ensured that the ceremony lasted no more than 40 minutes, taking place at an unconventional time of 7:00 am.

Religion held little significance for my father, and he approached superstitions and rituals with skepticism, especially when he found them to be a waste of time, effort, and money. For example, when he was advised that his married daughter should avoid going to her Sasural (in-laws’ home) on a Wednesday, considered inauspicious, he made it a point that she left on that very day. Similarly, during my second brother’s wedding in Nagpur, he challenged convention by having the wedding caravan of a dozen cars depart for Wardha exactly at midnight, arguing that people board trains at midnight without hesitation.

In a time when horoscope matching was common in marriages, my father took a different stance. He didn’t prioritize horoscope matching and never requested horoscopes for family marriages.

A few years later, my father encouraged and persuaded my sister-in-law, Kanta, who had just completed her matriculation, to enroll in college and pursue her graduation. Kanta Bhabhi joined a local art college shortly after her marriage and enjoyed the luxury of an Ambassador car that my father would send to pick her up from college. His bold, independent, and defiant nature set him apart from his contemporaries, making him a remarkable figure.

The word “awe” accurately describes the feelings he would evoke in our hearts-whenever we encountered him. Due to his British-influenced style and culture, our interactions with him were limited. However, we vividly remember his morning routine of tea served from a kettle and bread and butter. He would be dressed in a crisply starched and pressed Khadi Dhoti Kurta, wearing a Nehru Khadi cap and impeccably polished footwear, exuding a commanding persona that demanded respect.

Regrettably, he was unable to pass on his financial and business acumen to his children, and a wall of separation seemed to always exist between him and the rest of us. Our parents never expressed love through hugs, kisses, or verbal affirmations; it was simply assumed. We did not share our fears, hopes, or dreams with them. He always ate his meals alone, and children were not allowed, nor did they have the courage, to sit with him. He was not one for idle conversation, and we could not put our feet up or snack while studying. As a sign of respect for books, we always stood up when he entered the room and sat only when permission was granted.

My father could not even complete middle school, having failed to clear the seventh standard in his school in Kharangana village. Nevertheless, The Times of India and Economic Times arrived every morning at our home, and he could read and comprehend English, although his spoken language skills were rudimentary. Had it not been for this deficiency, he could have achieved greater heights. He was aware of this fact, and when we lived in Marwari Mohalla, he hired an English teacher, a Muslim man who charged 25 paise per day, to improve his spoken skills. The teacher started in a traditional manner, beginning with grammar, which my father could not tolerate. “I hired you to teach me to speak fluently, not for learning the nuances of English grammar,” he told the teacher, who was subsequently dismissed.

He always thought big and ridiculed those trapped in narrow mental lanes. A punctual man who valued plain speech, he ensured that everything started on time. All six of his children’s weddings took place on schedule, not a minute more or less. He did not believe in traditions, superstitions, or rituals. His quirks and temperament were well-known, and he never suffered fools gladly, always speaking his mind without guile or concern for the consequences.

His ruthlessness with others reflected his own ruthlessness. A perfectionist with an unwavering attention to detail, he abhorred any form of inaccuracy. He would meticulously scrutinize vouchers, ledgers, balance sheets, and account statements, ensuring that every number was precise and accurate.

*****

Today, my mind has been inundated with yet another vivid memory. It takes me back to the time when I joined the MD (Medicine) program at a medical college in Nagpur. During a casual conversation, my father inquired about the textbooks essential for my pursuit of an MD degree. I dutifully compiled a comprehensive list that encompassed various subjects, ranging from general medicine to specialized areas like cardiology, pulmonology, hepatology, neurology, and nephrology. As I handed him the list, a thought crossed my mind: “He would struggle to even pronounce, let alone spell, the names of these textbooks,” I thought to myself. But a month later, a thick parcel was delivered by the postman to my room in the post-graduate hostel at the Government Medical College. I didn’t know who had sent the heavy cardboard box and couldn’t anticipate its contents. When I opened it, I almost fell off my chair. The latest editions of all the textbooks that I had listed were in the box. Those textbooks must have cost close to Rs 4000 in those days, and I earned a princely salary of Rs 625 as a resident! Tears streamed down my cheeks, acknowledging the unvoiced love and affection that my father had for me.

*****

Between Dreams and Reality: A Father’s Vision and a Son’s Choice

In 1981, I successfully obtained my MD degree from Nagpur. Upon returning to Wardha, I completed my residency and soon joined the Medicine department of the Medical College at Sevagram. This career path I chose left my father feeling disillusioned. He had envisioned, quite rightly, that I would establish a private practice in the town where I had grown up, received my education, and where he had even arranged a building for Dr. BC Chandak—a fellow doctor who ran an OPD, a small ward, and a pathology and x-ray clinic on a temporary basis. It was my father’s desire for me to start my practice in that very building. The location was ideal, overlooking the bustling Indira market, situated on Dr. JC Kumarappa Road, and conveniently close to Maganwadi. With my father’s reputation, my MD degree, and the availability of financial resources, it seemed like the perfect opportunity to embark on a thriving private healthcare venture.

However, when I expressed my preference for an academic career rather than immersing myself in the private healthcare world, my father couldn’t hide his disappointment. Though he tried to mask his feelings, I could sense his realization of how much he had yearned for me to establish a private practice, to see me surrounded by patients in a clinic. His grand plans went awry. However, I must say that he didn’t impose his wishes on me and let me do what I wished to do.

*****

The Yin and Yang of Love

My mother and father were like two sides of a coin, contrasting yet complementary in nature. While my father embodied the qualities of generosity and risk-taking, my mother represented a stark contrast. Hailing from a small town, she held deep religious beliefs and found solace in visiting the temple. Her approach to life was marked by frugality and caution, standing in contrast to my father’s venturesome spirit and willingness to take risks.

Despite these differences, their contrasting qualities seemed to harmonize and bring balance to their relationship. Like almost every Hindu wife of old, my mother hadcompletely merged her identity in his. Like the interplay of khadi and silk, their contrasting personalities and perspectives complemented each other, creating a unique and harmonious dynamic. Together, they navigated life’s uncertainties, each offering their own strengths and finding common ground amidst their divergent approaches.

Despite coming from a humble village background, my father possessed a deep appreciation for aesthetics and the finer things in life. Even when it came to something as seemingly simple as a meal, he had a keen eye for detail and a particular way of arranging the dishes on a thali. Each component – be it the dal, rice, curry, roti, dahi, papad, salad, chutney, mango pickle, or sweet dish – had to follow a precise sequence.

To meet his exacting standards, my mother would swiftly spring into action as soon as he settled down to eat. With remarkable efficiency, she would take out the kneaded dough, roll it into a thin roti, and place it on the hot dry tawa. Holding it directly over the flame, she carefully monitored its cooking, ensuring it swelled with steam but didn’t burst. This delicate dance of culinary artistry would be completed in a matter of seconds, as my mother strived to deliver the perfect phulka to his plate. It had to be thin, soft, piping hot, and free from any unsightly burn marks.

These meticulous preparations exemplified my father’s attention to detail and his desire for perfection in every aspect of life, no matter how small or mundane. The dedication of my mother to meet his culinary preferences demonstrated their shared commitment to creating moments of delight and satisfaction, even in the simplest of daily routines.

*****

Conversations and Connections: The Cotton Trade Gatherings

During an annual meeting in Bombay, Rahul Bajaj approached him with curiosity. “Gokuldasji, you bring such a wealth of experience to our board. I notice that you comprehend everything we discuss during the company meetings, yet you rarely speak in English. Could you enlighten me about your educational background?” Rahul Bajaj inquired. My father calmly responded, “I have completed BCS.” Perceiving a mistake, Rahul Bajaj tried to correct him, saying, “No, you must mean BSc.” Without hesitation, my father clarified, “No, you misunderstood. BCS stands for Bachhraj Civil Service.”

In May 1972, Kamalnayanji Bajaj tragically passed away due to a heart attack at Raj Bhavan in Ahmedabad. Bhaiji, accompanied by Professor RK Vora, embarked on a journey to attend the funeral. They swiftly covered the 850-km distance from Wardha to Ahmedabad, urging the company driver to maintain a rapid pace and strictly forbidding him from glancing at the odometer. Bhaiji, known for his dislike of leisurely driving, always preferred to sit beside the driver.

My father had a great fondness for social gatherings and would often indulge in hosting parties. On one memorable occasion, he extended a warm invitation to Rahul Bajaj and his mother, Savitridevi, to visit our Yelakeli (or perhaps it was Umri or Mhasala?) farm. There, they were treated to a delightful spread of jhunka bhakar, baingan ka bharta, sweet dahi, freshly plucked sugarcane from the fields, and juicy oranges, showcasing the richness of our farm’s produce.

Additionally, every Friday evening held a special significance for my father as he would organize a Kaccha Chiwada party. This gathering would bring together cotton merchants and brokers from Wardha, fostering a sense of camaraderie and celebration. As they savored the traditional snack, made with poha (flattened rice), spices, and other delectable ingredients, conversations flowed, business connections strengthened, and the atmosphere buzzed with the energy of the cotton trade.

*****

A Stylish Icon: My Father’s Impeccable Sense of Fashion

My father took great pride in his impeccable sense of style. He sought out the finest and often most luxurious Andhra khadi fabric for his dhoti, shirts, and cap. No expense was spared to ensure that he was adorned in the finest attire.

To ensure a perfect fit, Hedau Tailor, a skilled tailor with a shop near Durga Talkies, would visit our home and meticulously measure my father. He would then place an order for a dozen-and-a-half shirts and caps at a time, demonstrating my father’s commitment to maintaining a well-stocked wardrobe. Each garment was subjected to the highest standards of care, with starching and pressing carried out to perfection. Not a single crease was tolerated, as my father demanded nothing less than flawlessness in his attire.

Even the smallest detail mattered to my father. If the cap’s fabric did not meet his exacting standards after being ironed, he would request the dhobi to press it again until it met his expectations

In a surprising twist, after reaching the age of 67, my father, who had always been clean-shaven, took us all by surprise by cultivating a thick salt-and-pepper mustache. This new addition to his face, coupled with the addition of dark sunglasses, lent him an air of mystery and intrigue. The reasons behind his decision to change his appearance remain unknown to me, but there was no denying that it made him even more distinctive and eye-catching.

*****

Going the Extra Mile: A Tale of Generosity and Mentorship

My father also cared for the unprivileged. In the late 1960s, Jaishree Bhavan provided accommodation for many young Marwari students, including Parmanand Tapdiya (doing CA), Kamal Gandhi (doing B Com), Vallabh Rathi (doing M Com), Bhattad, and others. Shankar Agnihotri, Madanlal Mohta, and Keshavlal Patel later joined them. My father not only provided them with a roof over their heads, but also made sure they woke up early, went for walks, ran a few kilometers, or played football. He also supported many of them financially. Tapdiyaji, in particular, is grateful and recalls my father’s generosity almost every year. “But for him, my dream of becoming a Chartered Accountant might have turned into a nightmare,” he acknowledges.

I have a vivid recollection of a remarkable incident that truly showcased my father’s extraordinary kindness. It took place in 1965 when Parmanand Tapdiya, an 18-year-old boy from a humble background, was in search of an articleship firm. Tapdiya, who had recently completed his B.Com with outstanding performance, was not only talented but also had a long-standing acquaintance with my father. He however, lacked enough money to study further.

Recognizing his potential, my father went above and beyond to help him. He personally recommended Tapdiyaji to KK Mankeshwar and Company, a prestigious auditing firm in Nagpur that dealt with prominent clients like Jamnalal Sons and the Bachhraj Group. Accompanied by a letter from my father, Tapdiyaji visited Mr. Mankeshwar’s office with the hope of securing a position where he could learn the fundamentals of accountancy and finance.

However, on his first day at the office, Tapdiyaji faced a setback. He was turned away due to his attire—an informal shirt and pyjamas— which did not meet the formal dress code requirements. Moreover, he lacked the necessary funds to pay the substantial deposit that was expected.

On the 8th of May 1965, amidst the bustling wedding preparations for my sister Pushpa, Tapdiyaji made his way to Wardha and sought out my father. Despite the flurry of activities surrounding the wedding, my father sensed something was amiss and inquired about Tapdiyaji’s visit. It was then that Tapdiyaji shared the disheartening incident that had transpired at the office.

“I went to Mr. Mankeshwar’s office wearing a kurta, pyjamas, and a pair of chappals. He took one look at my attire and promptly showed me the door, cautioning me against entering his office without proper formal clothing. I don’t own a formal dress, nor do I have enough money to purchase one,” Tapdiyaji sheepishly revealed the story.

Without hesitation, my father sprang into action. He provided Tapdiyaji with the necessary funds to buy suitable clothing, allowed him to use our family car for commuting, and personally vouched for the required deposit.

This incident left a lasting impact on Tapdiyaji, so much so that he documented it in his book titled “The Iron Will,” which was released on his 78th birthday in June 2023. Tapdiyaji expressed his profound gratitude for this act of kindness, acknowledging its significant influence on his life even after six decades had passed. For the next two decades until my father’s untimely demise in 1986, Tapdiyaji faithfully visited our home, Jaishree Bhavan, every Dussehra to pay his respects—a testament to the enduring bond and gratitude between them. Even after my father’s sudden passing, Tapdiyaji continued this tradition until my mother’s demise in 2005. Following my father’s passing, he came to Jaishree Bhavan to visit my mother, touching her feet and being overwhelmed with memories, cried inconsolably.

Six decades later, Tapdiyaji has not forgotten that fateful day. He frequently shares this heartwarming story, consistently expressing his heartfelt gratitude towards my father.

*****

Fiery Temper and Unyielding Convictions

As I reflect on my father and attempt to capture his essence, I grapple with the question of how to present him truthfully, flaws and all, while still honoring his memory and the positive impact he had on my life. It is important to acknowledge his humanity, complete with his imperfections, while also highlighting the valuable lessons he imparted and the love he shared.

One of my father’s notable shortcomings was his tendency towards arrogance, a trait he openly exhibited. He possessed a fiery temper and little patience for those who held opposing views. He lived by the mantra of “either you’re with me or against me,” a mindset that likely contributed to strained relationships with his nephew and all four of his sisters, leading to a breakdown in communication in their later years. Furthermore, he often treated his subordinates with contempt, lacking the capacity to suffer fools gladly. His aloofness and reluctance to visit the homes of friends and acquaintances created a sense of distance between him and society.

Yet, it is crucial to recognize that beneath these flaws, my father demonstrated unwavering commitment to his own principles and beliefs. He lived life on his own terms, refusing to compromise or be swayed by external influences. This resolute nature both garnered respect and drew criticism. Through his example, he instilled in me the importance of staying true to oneself, even in the face of adversity, and the significance of standing up for what one believes in.

*****

राधाकृष्णजी और अनसूया बजाज

My father shared a profound and enduring bond with Radhakrishnaji and Ansuya Bajaj, a relationship that spanned several decades, from the 1940s until his own passing. He held them in the highest regard, recognizing their significant contributions to the Khadi movement and their unwavering dedication to social causes. Radhakrishnaji, who was born in 1905, was eleven years older than my father and hailed from Kasi Ka Baas, a village situated 12 km from Sikar in Rajasthan. Similar to my father, Radhakrishnaji also lost his father at a young age in 1910 when he was merely five years old.

At the request of Jamnalalji Bajaj, the entire Bajaj family relocated to Wardha, where Radhakrishnaji devoted his life to rural development, the empowerment of women, Sarvodaya (the welfare of all), and Go-Seva (cow protection). He worked closely with notable figures such as Mahatma Gandhi, Vinoba Bhave, and Kaka Kalelkar, actively participating in their initiatives and movements. Radhakrishnaji was deeply involved with the Laxmi Narayan Mandir, a temple built by Bachhraj Bajaj, which was the first temple in India to be opened to Harijans (untouchables) by Jamnalalji Bajaj on July 17, 1928. Prior to her passing, Sadibai, the wife of Bachhraj Bajaj, expressed her wish for her cash savings of Rs 100,000 to be used for the construction of the Laxmi Narayan Temple. The temple was completed in 22 months, at a total cost of Rs 175,000.

Radhakrishnaji Bajaj was appointed a trustee of Mandir on July 18, 1933, and later became its chairman on March 2, 1942, a position he held for 60 years.

As my father started working at the Laxmi Narayan Mandir in 1940, eventually rising to the position of trustee, he caught the attention of Radhakrishnaji. With unwavering determination and steadfastness, my father would tirelessly work long hours to complete his assigned tasks. Regardless of scorching sun or drenching rains, he would be found in the office, the Mandir, or by Radhakrishnaji’s side. Twice a day, he would cycle to Gopuri, diligently reporting everything that had transpired during the day.

His ability to engage in sustained hard work, coupled with his honesty, integrity, and attention to detail, did not go unnoticed. Over the years, a mutual liking and respect developed between them. Their relationship took root, flourished, and blossomed. My father became a trusted member of Radhakrishnaji’s family.

Radhakrishnaji dedicated his life to the field of Khadi, the welfare of women, rural development, Sarvodaya, Go-Seva, and worked closely with Gandhi, Vinoba, and Kalelkar. He was also deeply involved with the Laxmi Narayan Mandir, the temple constructed by Bachhraj Bajaj, which was the first temple in India to be opened to Harijans by Jamnalalji Bajaj on 17 July 1928. Radhakrishnaji was appointed as a trustee of the Mandir on 18 July 1933 and became its chairman on 2 March 1942, a post he held for sixty years.

Both Radhakrishnaji and Anusuya Buaji placed their trust in my father, confiding in him about their family, financial, and personal matters. He never failed to support them in their times of need. Despite not being related by blood, their bond was forged through shared emotions and sentiments, which is why Anusuya Buaji started tying Rakhi to him as a symbol of their deep connection. In her autobiography, “Jaako Raakhe Gomaiya,” Anusuya Bai even wrote a letter expressing her wish for my father to take care of her children if she were no longer alive.

One memorable incident occurred during my sixth-grade year at Craddock High School when Radhakrishnaji discovered my passion for books.Swarajya Bhandar, located near Subzi Mandi, stocked thousands of Hindi and Marathi books on a variety of subjects. To nurture my love for reading, Radhakrishnaji generously opened the doors of this bookstore for me. He encouraged me to explore the shop and select as many books as I desired. With his support, the bookstore staff allowed me to spend as much time as I needed, freely browsing the shelves. Over the following years, Radhakrishnaji personally covered the cost of every book I chose from the store. I delved into countless volumes, immersing myself in their pages, Over the next few years, he paid for every book that I picked up from the store. I must have read hundreds of books, and his gesture stoked the flames of bibliophilia in my heart, making me a lifelong book lover.

During my father’s most challenging moments, when his reputation was under attack and people sought to tarnish his image, Radhakrishnaji provided unwavering support. He became a steadfast pillar, offering a shoulder to lean on and a voice of reason. In times of trial and tribulation, he stood by my father’s side, defending him and advocating on his behalf.

Radhakrishnaji and Anusuya Buaji held an irreplaceable position in my father’s life, and his devotion to them was unwavering. When my father passed away, at the age of 81, Radhakrishnaji accompanied Bhavana, my nephew Anand, and me to Haridwar. Despite the long journey in a non-AC compartment on the Dakshin Express, he remained by our side. In Haridwar, he guided us as we immersed my father’s ashes in the holy waters of the Ganges. It was a deeply personal and meaningful moment, and Radhakrishnaji respected our decision not to involve any priests or follow traditional rituals. This choice was aligned with my father’s own beliefs, and Radhakrishnaji honored it wholeheartedly.

*****

Advocating for his Daughter-in-Law’s College Education

In 1969, my elder brother Ashok married Kanta bhabhi, who came from the town of Bhatkuli near Amravati. On the wedding day, our procession embarked from Wardha towards Amravati, with the last car waiting for me. I had just completed my 7th-grade final exam, and as soon as I finished, I hurriedly joined the car parked near the school gate. My mother had specially tailored a set of shirts and pants for me, and I felt a sense of pride knowing that my father had arranged a car exclusively for my transportation.

After her marriage, Kanta bhabhi enrolled in Yeshwant Arts College in Wardha to pursue an Art degree. She also obtained a Hindi degree called Kovid, conferred by Rashtrabhasha Prachar Samiti. Occasionally, she would commute to college in a chauffeur-driven Ambassador car. In the late sixties, it was unconventional for a Marwari daughter-in-law to attend college. However, my father was firm in his belief that his daughter-in-law should receive a college education, and he successfully convinced her to go to the college.

*****

Asha’s Wedding on Vasant Panchmi

Asha’s wedding took place on February 1, 1960, coinciding with the auspicious Hindu festival of Vasant Panchmi. Bhaiji had meticulously planned the event to make it the talk of the town. He had informed the Singhi family that the arrangements would be based on the number of Baraatis (wedding procession participants) attending. Just under fifty Baraatis arrived from Indore by bus and were graciously accommodated at Bajaj Wadi, our family residence. Uttambhau, Professor Ram Krishna Vora, and Mira Bai Mundra took charge of the Baraat procession. The Baraatis were treated to three sumptuous sit-down meals during their stay in Wardha. The teachers from Mahila Ashram school, dressed in white khadi saris, served the guests. Instead of the usual band or music group, the melodious notes of a shehnai filled the air. Fresh fruits were elegantly arranged with knives and forks, adding a touch of sophistication.

The wedding rituals were conducted by Chimanilalji Shastri, Bhaiji’s trusted Pundit. Bhaiji aimed to complete the wedding ceremony within 35 minutes, and he successfully achieved this feat. The wedding took place at Godhuli Bela, around 6 pm, symbolizing the time when cows return home, and it was attended by a large audience. The dining area was adorned with beautiful Rangoli designs, and the fragrance of Agarbattis (incense sticks) filled the air. The food was served with great care and attention to detail, and the highlight of the occasion was the presence of specially fitted wall fans, a rare luxury in those days.

The Baraat from Indore stayed at Bajaj Wadi, Wardha.

During the wedding ceremony, the esteemed spiritual saint Tukdoji Maharaj, beloved by the people of Vidarbha, graced the occasion and blessed everyone with his presence. He also delighted the attendees by singing a soulful bhajan, adding a spiritual touch to the festivities.

Shri Chiranjilalji Badjate, a respected individual, gifted copies of Mahatma Gandhi’s books to all the Baraatis, symbolizing his admiration for Gandhiji’s principles and teachings. Additionally, Tauji (elder uncle) presented each Baraati with a silver glass, which cost Rs. 7 per piece, as a token of his blessings and well-wishes.

Bhaiji had entrusted Tauji with the task of procuring gold ornaments worth 15 tolas from Khamgaon for Asha. In 1960, one tola of gold cost Rs. 1300. As per Bhaiji’s request, Badibai received a beautiful assortment of jewelry, including a necklace, bangles, earrings, and a mangal sutra, symbolizing the sacred bond of marriage.

For the wedding, Ansuyabai Bajaj, the wife of Shri Radhakisanji Bajaj and Bhaiji’s Rakhi sister, had ordered half a dozen saris from Benares. Upon their arrival, two saris were selected for the wedding, while the remaining four were returned, resembling the process of returning items in the era of online shopping. The cost of the two chosen saris was Rs. 120 and Rs. 70. Interestingly, Asha decided to wear the Rs. 70 red sari for her wedding ceremony, showcasing simplicity and elegance. Jijaji (brother-in-law) donned a Chudidar Sherwani and wore different suits for the three functions held in Wardha.

The wedding turned out to be a significant expense, amounting to Rs. 13,000 for Bhaiji. To provide context in today’s terms, 100 rupees in 1960 is equivalent to approximately 8,584 rupees in 2022. Initially, Tauji had offered to cover all the expenses, but he backed out at the last moment. Eventually, he shared one-third of the total expenses incurred.

*****

Unconventional Timing: Rescheduling Pushpa’s Wedding

Pushpa’s wedding was initially planned for midnight on May 11, 1965, as suggested by the Pundit for its auspiciousness. However, my father held a different perspective. Despite his Marwari background, he did not place much importance on rituals or daily puja. “I want the whole world to witness the wedding,” he declared, and he successfully convinced the groom’s father to reschedule the ceremony for 7 am instead. This was an unconventional request within the Marwari community in Wardha, but my father remained firm in his decision.

Bhaiji was known for his strict and unwavering nature, and true to his character, the wedding commenced promptly at 7 am, concluding within a swift 35 minutes. He even managed to persuade Jankidevi Bajaj, the wife of Seth Jamnalal Bajaj, to attend the wedding and deliver a speech on the occasion. Jiji (sister) received a generous wedding gift from her parents, consisting of 20 tolas of gold and 5 kg of silver.

The Baraat, comprising mainly individuals from Sirri and Seloo, stayed at the Bajaj Electricity home. They arrived in the morning and departed after a sumptuous lunch, participating in the celebration of this joyous union.

When it came to details of any function, my father would not compromise. In April 1969, Ashok was to marry Kanta Bhabhi in Bhatkuli, Amravati district. My father sent Om and Tarachandji to Bhatkuli to ensure that the wedding platform was built properly with bricks and all the arrangements were immaculate.

My father was also a stickler for discipline and made sure that all the wedding ceremonies started at the precise time. He would not wait even a second if the invitees were not present in sufficient numbers.

*****

चार धाम यात्रा

In 1960, my father, mother, three sisters, and his brother embarked on a two-month-long Char Dham tour, organized by Tukdoji Maharaj. While on their way, a bus carrying passengers to Yamunotri fell into a gorge in the Uttarkashi district, resulting in many deaths and injuries. Word quickly spread that my father was on the bus, and despite the fact that the passengers who lost their lives were from Warora, people mistakenly believed that it was from Wardha. Local newspapers even reported the news incorrectly.

To ensure the safety of the children, Bai and Bhaiji sent them to their Nanaji’s home while they continued the Yaatra. Mr. Brijlal from Bachhraj Factories was sent to Barshi to bring the children back home. Upon their arrival, Professor RK Vora visited our home and asked Badibai and Jiji if they had read the newspaper. They replied negatively, and he took them and my brothers with him to offer Rs. 11 at Laxmi Narayan Mandir to pray for my father’s well-being.

Fortunately, my father had gotten off the bus at the last moment as it could not accommodate additional passengers. Shortly after he left, the bus fell into a valley. He miraculously survived the incident. Shambhuji Padoles’ son-in-law sent a telegram to Wardha to inform them that everything was okay. My father had written a diary narrating the entire journey. Unfortunately, it has been misplaced.

*****

A Brush with Illness: My Father’s First Heart Attack

On July 7, 1977, my father experienced his first heart attack and was admitted to the Government Medical College in Nagpur. During that time, the treatment options for a heart attack were limited compared to today’s medical advancements. There were no blood thinners, clot busters, cholesterol-lowering medications, angiographies, or angioplasties available. His treatment primarily involved mandatory bed rest and the use of sorbitrate tablets.