During the seventies, Sevagram was inhabited by simple folks, dealing with their lives in a uniquely engaging, humorous and humane manner. The medical college had just started and boys and girls from Ambala to Ahmednagar and Shahjahanpur to Sambhaji Nagar arrived in the village. Sevagram pleased many no end. Many were overjoyed, but many were silently sulking in their rooms. Many were on cloud nine, for admission to medical college, guaranteed that they would emerge as doctors. However, many complained bitterly about their situation—they found the village too sleepy and boring—but there was no way out.

The boys and men soon found comfort in Sevagram. They discovered 𝐂𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐚𝐦𝐚𝐧, a young barber in his mid-twenties. Here is his story.

Chintamani was born in 1947 to Vithoba Vaidya, a professional barber in Waifad village located 27 km west of Sevagram. Legend has it that his grandfather, a barber who also practised traditional medicine, earned the family nickname “Vaidya,” leading them to adopt it as their surname.

Despite passing 12th grade in Wardha, Chintamani didn’t find education interesting or exciting, and in 1970, he decided to follow in his father’s footsteps and move to Sevagram.

And so, the first amateur barber set foot on Sevagram soil.

The Initial Days

Sevagram Medical College had only been operating for a year when Chintamani started his business as a street-side barber. From dawn to dusk he would offer his services on the street that led to Gandhi’s ashram, very close to the old hospital building. He had no radio or television set to distract him from the job. He occasionally nicked his customers with his old-fashioned straight razor and left behind some abrasions, but they never complained. They gladly endured his assaults over their scalps, and seldom complained if he messed up their haircut.

Chintamani’s third-generation barber genes and his self-taught skills allowed him to quickly establish himself in the trade. He was known for his patience and gentle touch and gained a reputation for leaving a lasting impression on his customers.

His name quickly travelled far and wide—earning him a reputation of being a barber who won’t make your hair stand on end when you sat on his chair. His customers left his shop feeling satisfied with their haircuts, which helped establish his reputation as a skilled barber.

After a year, he rented a shop near the Madras Hotel. Due to the growth of his business, Chintamani relocated his shop from near the Madras Hotel to Seth Mathuradas Mohta Dharamshala. In 1990, he rented another shop in the same building, and his son Kiran pays a monthly rent of Rs 1368 to continue the family legacy.

Kalpana Cutting Salon,” named after his daughter, began to flourish. According to Kiran, Chintamani’s son, “In those days, my father only had a Ustara (a sharp razor), a pair of scissors, combs, a shaving brush, a small mirror, and a Godrej soap. He would wrap a piece of cloth around the customer’s neck – it had been used on dozens of necks before it was considered worth washing – and then offer them a small mirror to admire their new haircut after he had finished. Satisfied customers would appreciate his skills and happily pay his fees before walking out of his shop.”

Moving into a new shop

Chintaman received tremendous support from Annasaheb Sastrabuddhe when he moved to his new shop. Previously, Chintaman had been using old, worn-out wooden chairs, but thanks to Annasaheb’s intervention, he was able to order new, high-quality saloon chairs from Bombay. When the chairs arrived at the shop, Chintaman was overwhelmed with gratitude. Annasaheb not only helped with the chair order, but he also raised funds to pay for them, showing his generosity and commitment to helping others.

“My father knew how to sharpen the saw—no, Ustara,” recalled Kiran, the son of Chintamani Vaidya, as he showed me the old Ustara his father used in the 1970s, the very razor he used to cut the hair of the professors of the medical college. He also preserved a steel Katori that his father used in the shop, dating back to 1968.

“My father would spend his quiet days sharpening his scissors and cleaning his shop, always preparing for the next customer who would walk through the door,” Kiran added.

In 1980, the family moved to Karanji Bhoge, a village 3 km south of Sevagram. He purchased three acres of land in the village and rented a mud-plastered thatched hut. Years later, as he began earning a decent living, he built a pukka house.

During that time, the roads leading to Sevagram were all muddy, and there were no buses or auto-rickshaws available to travel on those routes.

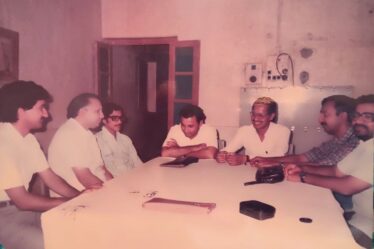

” To begin with, ours was the only barber shop in Sevagram. Almost all professors—Dr KN Ingley, OP Gupta, R Narang, VN Chaturvedi, Ahuja, Rajkumar, KK Trivedi, Shetty and AP Jain—used to regularly come to my father. Dr ID Singh was the only professor who never came to our shop,” his son told me. “For he was a Sikh,” he mischievously explained.

Barber Par Excellence

Slowly but surely, people began to realize that the barber shop was not just a place to get a haircut, but a place where they could go for a friendly chat and a warm welcome.

Nothing could beat his traditional shave with an open blade. He would pamper young men by carefully preparing their stubble with Godrej shaving soap and a not-so-soft brush. It was the closest—not necessarily the smoothest—shave his customers experienced. Villagers would travel miles to get a haircut from Chintamani, not because they valued his skills, but because he was the only barber in the village.

The barbershop also acted as a community centre for unemployed youth. During an average day, young men were constantly in and out of the shop—not to get a shave, but just to admire themselves in the mirror and comb their hair. Chintamani didn’t mind this, and it was all free of cost.

People would come to the barbershop every day in the afternoon and sit there until evening, reading Marathi newspapers, listening to the radio, gossiping, discussing village politics, and watching the world go by. The barber shop also doubled up as a community centre.

“Unlike today, nobody in those days would come to my shop to look their best for an important occasion or their big day. I don’t recall a groom coming to me to get their hair in shape, nor did I deliver the sharpest cut for the wedding day,” Chintamani recalled when I cycled to his home to interview him.

A barber’s chair can be as taxing as a dentist’s chair. Customers should never be left unengaged or bored when they endure a haircut,” he explained. Using his soft skills of conversation-making, he would divert his customers’ minds while he worked.

Not much,” Kiran replied. “In 1971, a haircut cost 25 paise, and shaving was an additional 10 paise. But by the early nineties, when I joined my father, we charged Rs One for a haircut and fifty paise for shaving.”

Sevagram was a small village, and their barbershop was the only one in town, so people from neighbouring villages, medical students, paramedics, and later engineering college students, would visit them for their haircuts.

At one time, Maroti Shirastan, worked under Chintamani’s tutelage. They worked together for 10 years before parting ways. At the height of their success, they had as many as five chairs in the shop and worked from 7 am until well past midnight.

Chintamani was also known for taking young men under his wing and teaching them the art of barbering. Many of them were quick learners and became experts in their own right.

Going Down Memory Lane

“Almost all the barbers in the neighbouring villages did their internships under my father,” Kiran reminisced. “Before starting their own shops in villages such as Karanji Bhoge, Karanji Kazi, Madni, Taroda, Mandgaon, Hamdapur, Kharangana Gode, Kutki, Chanki, Kopra, Nandura, Mandavgarh, Dhanora, Bhankheda, Yesamba and Goji.

One time, a foreign visitor came to Sevagram and needed a haircut. He stumbled upon Chintamani’s shop and nervously communicated his request, hoping to find someone who could speak English. Chintamani understood the man’s request and gave him a nice haircut. As the visitor was about to leave, he realized he didn’t have any Indian currency to pay for the haircut. Chintamani didn’t know how to convert the foreign currency into Indian rupees, so he simply accepted a few coins the visitor had in his pocket, and thanked him for his business. The visitor was impressed with the humble barber’s hospitality and promised to send him some Indian currency later, which he did.

Those days were really simple. The V-John shaving cream; Axe and Old Spice aftershaves; Pantene, Dove and Sunsilk shampoos; conditioners and moisturisers were yet to arrive on the shelves of barbershops. No barber posted his work on their Instagrams—for the Instagrams didn’t exist. And the term Nai or Hajjam was not derogatory.

Came the eighties and the world changed. So did Chintamani. Now, students from the Engineering College and medical school would compete for a spot in his chair.

An MGIMS alumnus described how the professors acted as the moral guardian of the barber’s shops. Reads his recent WhatsApp post: “The salon walls were now adored with the posters of popular singers and bands from the 1980s— Disco Song singers, the A-Ha band, stars—and their unique hairstyles. On the next visit, I see, not one poster on the wall. Where did the posters go? Vanished without a trace?

An MGIMS professor (name and department withheld), now his weekly customer, had ordered the posters to be pulled down “so that they do not corrupt the minds or rather the heads of the MGIMS students.” Chintamani was left with no option but to take the posters off.

Anand Shankar Dixit, a house officer in Medicine belonging to the 1976 batch, went to Chintamani for a haircut in the early 1980s. Halfway through the haircut, Dr. OP Gupta arrived at the salon

Dixit eyed him and immediately stood up, reverently asking Dr Gupta to take his seat. Dr Gupta tried to prevail upon him, arguing that he needed to complete his haircut, but the obedient house officer would have none of it. Finally, Dr Gupta made a pretence of some urgent work and left the salon, letting Chintamani finish his job.

The door-to-door barber is a dying breed. In those days, Chintamani would visit all the professors, offering them a decent haircut as they read newspapers on their lawns. In the old days, barbers also doubled as matrimonial agents or marriage brokers, carrying news of eligible bachelors and brides to the households they visited. I am not sure if Chintamani ever indulged in such extra-professional activities, which people from his ilk in North India regularly practised.

Then and Now

In those days, the rapidly flourishing Rs 10,000 crore hair and beauty industry didn’t exist in small villages. Surely Chintamani would never have imagined in his wildest dreams, that one day the multinational giant L’Oréal alone would have over 4,000 hair salons in 70 cities across India. He belonged to an era when the Salon and Beauty Parlours Association (SBPA) did not exist in Maharashtra.

For him, hair on men’s scalps had to be cut, not dressed; to be snipped off, not styled. Neither he nor his son could adapt to the changing landscape of the haircare industry. The air-conditioned state-of-the-art hair salons and spas, the chic salon décor, the urbane language, and the demeanour—these are all things that hair salons in villages lack. This barber shop is neither modern nor fancy and cannot boast of all the latest equipment and products. How will they adapt themselves to modern times?

I could sense the worry weighing heavily on their minds.

The father and son had worked hard all their lives to build a reputation as the best barbers in the village. Now, it seemed like everything was slipping away. Despite their fears, Kiran hadn’t given up. He continued to work every day, always with a smile on his face and a kind word for those who came into his shop.

The very thought that once upon a time, distinguished doctors and venerated teachers had bowed their heads before them and carried out all the neck drills that they dictated as they sat on their salon chairs, left a highly satisfying sense of accomplishment in their hearts.

Little wonder, when Dr Krishan Aggarwal (MGIMS Class of 1975) was awarded the Padma Shri in 2010, and the news was flashed on the television sets of the neighbouring shops, Chintamani’s chest swelled with pride.

“Between 1975 and 1983, Dr Krishan would come to me for his haircut and I would make him bow his head before me,” he told the audience.

As Chintamani grew older, he began to feel the effects of age, and he eventually had to retire. Content with knowing that his legacy would live on through Kiran, his son, he lives a retired life in Karanji Bhoge, barely three km from Sevagram.

Hair today, gone tomorrow.

Excellent description!

Thank you SP Kalantri Sir.

Reading, took me back to Sevagram days.

Never knew his father was part of the “United Company of Barber Surgeons

Dear S P Kalantri, very well written.

SB Deshmukh 69 batch

Excellent.

Very well written Sir

Excellent piece. Rekindled memories. In 80s he had an electric radio set playing non stop. I was a reluctant customer initially (as did not have choice), soon became a fan.

Dear Dr. SP,

Your writing is superb. Takes us to all the formative stages of Medical education. Am from 75 batch. Really studying at MGIMS and staying at Sewagram was a very good experience. Thanks.

Yes, we used to get haircut by Chintaman after 1970, but during our admission in 1969 we had to go Wardha for haircut. Really it was egoless days at MGIMS. We forgot to meet him during our golden jubilee celebrations in January 2019. We had invited Shri Babulal, the canteen owner and financer but missed out Chintaman.

Very aptly described. I regularly visited his saloon since I joined MGIMS in 86, initially in Dharmshala and later in the shopping complex. Even now when I visit Sevagram and if stay for more than two- three days, I visit his saloon. This time I visited on Jan 23 and had my moustaches trimmed. And as usual Kiran refused to take money as this was a small job for him. The simplicity and humbleness is essence of Sevagram lived through these people. Thank you for making us revisit the memory lane.

SP, you must write book on your memories. What an excellent way to write.

Feeling nostalgic. Thank you for sharing the memories with such a wonderful write-up, SP Kalantri Sir.

Gems from the past!

This reads like R.K Narayan’s Malgudi Days.

Beautifully penned! As always ! We want to read more. 👍

Very nice, sir. Thanks for sharing this article. 🙏🙏🙏

SP,

Thanks for thinking of me and sharing this.

To quote a Marathi poet —

“साध्याही विषयात आशय कधी मोठा किती आढळे,

नित्याच्या अवलोकने जन परी होती किती आंधळे”….

You will be surprised, and enjoy the coincidence, that I had almost similar character of a barber around me for about 20 years.

Your article of this व्यक्तिचित्र is enchanting and sensitive.

CONGRATS !👏

Keep writing on such organic aspects of life too. 💪

By the way, in a very different way पु.ल.(देशपांडे) has depicted a character of a barber and his encounter with him, in his famous book असा मी असामी –quite hilarious and sensitive.

“Chronicles of Sevagram” – i’m enjoying this

Sir want daily edition

So beautifully expressed Sir!

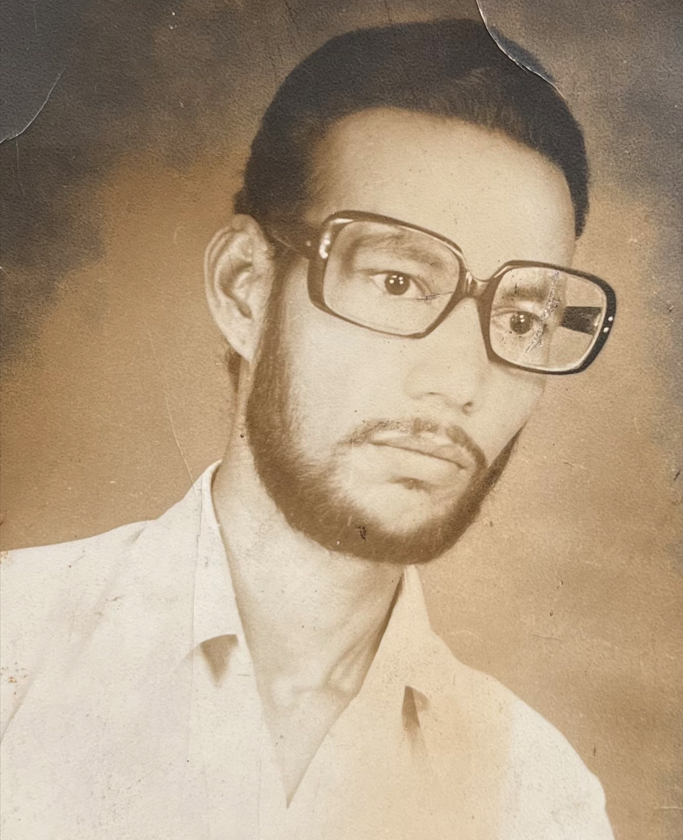

This blog brings so many memories of his saloon, which was right next to Goras. Will look forward to Chintaman’s photograph or an image of Kalpana saloon.

There is a very interesting twist to Chintamani. The next shop was Mehboob tailor. And of course, Chintamani was an all-gents tailor, though he did do a haircut for my younger sister Nandini. @Nandini Gokulchandran. Her famous “SADHANA CUT” was by Chintamani until she became wise otherwise and refused to step into his shop😁. But that’s not the titbit. Chintamani used to be the source of nonstop Hindi songs. He had a radio which will keep belting Bollywood songs from the time shop opened till he shut the shop. He knew exactly when one program ended and he’d start the next station, without missing a beat. He was a tall person with long hands and his radio used to be hung on the window. …. Thank you again SP Kalantri sir to have kindled another nostalgic memory from the past. I feel as if I am walking the corridors of Dharamshala.

I don’t remember my first haircut from him. But two incidents still stand out. The First was during my 7th std at KVM. I joined NCC and voila hairs below my temple vanished and those above it were military regulation: 2.5 mm long. The second instance is after my dad’s death. I didn’t know who had called him. But he was there. Standing quietly beside me and tonsuring my head gently, as if conveying to me how lucky I was—the son of a great father, teacher and a wonderful human being.