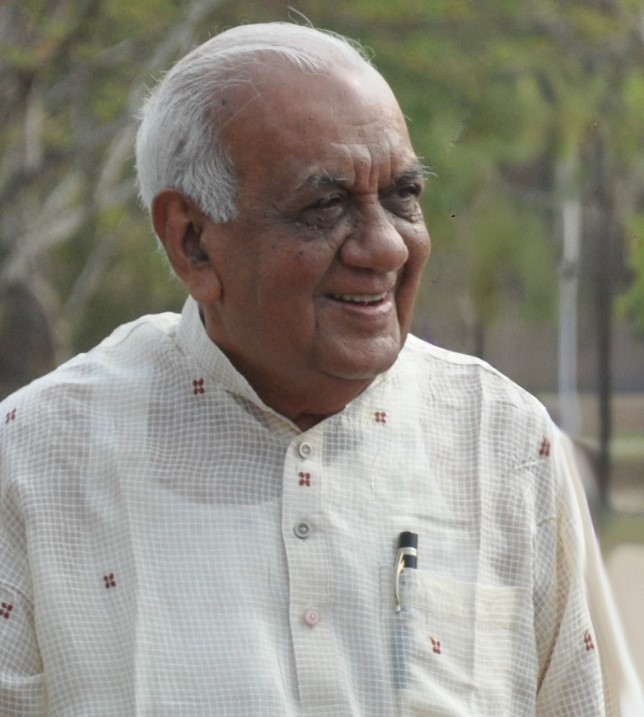

(1936-2024)

It is with deep sorrow that we announce the passing of Dhirubhai Mehta, President of Kasturba Health Society, Sevagram, who left us this morning.

He was just about to turn 88 this weekend.

Born on April 27, 1936, in Songadh, a village 28 km west of Bhavnagar, Gujarat, Dhirubhai came from a middle-class family. His upbringing was influenced by his parents’ values: his mother’s deep religiosity and commitment to moral principles, and his father’s emphasis on instilling strong moral values in their nine children despite limited resources. These formative influences deeply shaped Dhirubhai’s character and worldview.

He went on to preside one of the best medical schools in the country.

Dhirubhai’s schooling was in a Gujarati Medium school in his village where he studied up to the 7th standard. A brilliant student, after matriculation, he joined the Sydenham College of Commerce and Economics, Mumbai and in the summer of 1957, he graduated with a B.Com (Hon) from Mumbai University. He then pursued Chartered Accountancy. To finance his education and support his family, he gave tuitions and worked part-time. He passed both CA examinations on his first attempt, earning his CA degree in 1961 and becoming the 5635th certified Chartered Accountant in the country.

Fascinated by Khadi and inspired by Gandhi’s principles, Dhirubhai embraced Khadi at a young age, starting in 1954. He strongly believed that Khadi bonded rich and poor, and equated Khadi to self-reliance and self-government. The seeds of patriotism and virtuousness were sown early on in Dhirubhai’s life.

On May 1, 1966, Dhirubhai married Nandini Bajaj, daughter of Shri Radhakrishnaji Bajaj and granddaughter of Shrikrishnadas Jajoo, a revered freedom fighter and prominent Gandhian. This union not only brought Dhirubhai into the Bajaj family but also connected him to the Bajaj Group, a corporate powerhouse. The support and encouragement he received from the both Bajaj played a huge role in his personal and professional growth. He had a long and fruitful tenure with the Bajaj Group, spanning three generations—Kamalnayan Bajaj, Ramkrishna Bajaj, and Rahul Bajaj—over five decades.

Dhirubhai was not born into riches, nor was he ever spoon-fed success and fame. But he always believed in himself and made it big in his life. He had a razor-shop financial mind and uncanny financial wizardry. In 1966, he met Mr. Kamalnayan Bajaj, the architect of the Bajaj group. At Mr. Bajaj’s behest, he joined Bajaj group in 1966 until two decades later, he voluntarily, and prematurely, retired from professional life in 1986.

With no influential connections, Dhirubhai Mehta’s ascent was swift. He impressed the Bajaj family with his expertise in finance, investment, taxation and corporate management, coupled with a touch of humor and wit.

During the early seventies, he played a crucial role in navigating a prolonged legal dispute between the Bajaj group and Piaggio of Italy over the Vespa scooter, showcasing his dedication and expertise. Throughout his tenure, he earned the trust of key figures within the Bajaj family, emerging as a valued confidant.

Throughout his tenure with Bajaj, he earned the trust of Kamalnayan, Ramakrishna, and Rahul Bajaj, becoming a valued confidant.

Decades later, when a family dispute erupted between Kushagra and his father Shishir on one side, and Rahul along with three other cousins (Shekhar, Madhur, and Niraj) on the other, the Bajaj family sought Dhirubhai’s help to resolve the conflict. True to his impartial nature, Dhirubhai refused to take sides and facilitated a memorandum of understanding in February 2004. Although the solution he proposed didn’t endure, this event underscores the immense trust the entire Bajaj family placed in Dhirubhai.

Beyond his contributions to the Bajaj group, Dhirubhai served on various regulatory committees and held a directorship at Mukand Iron & Steel Works Limited. His commitment to ethical principles extended into every aspect of his professional life, earning him respect and admiration in both business and political circles.

At the age of fifty, Dhirubhai faced a difficult decision. He decided to quit Bajaj Auto and work full time in the not-for-profit health and education sector. “It was a tough call for me,” he admitted. “Nirad and Maitry were still pursuing their education, with Nirad aspiring to complete his commerce studies at prestigious universities in the USA. It required financial resources. However, my family stood by me and fully supported my choice.” His children ultimately pursued careers as chartered accountants. “It seems to be a genetic predisposition,” he would joke, “but I’m glad they achieved it independently, without relying on me or asking for financial assistance.

Although his professional moorings were in business and industry, Dhirubhai began wondering if it was worth spending all his life in the corridors of the corporate world.

Had Dhirubhai continued his stint, Bajaj Auto shares would have touched new heights, but a medical school would have been a loser.

From the land of capitalism, Mumbai, he came to Sevagram. Sevagram was not a new place for Dhirubhai- his wife came from Wardha and he used to visit the city frequently because Bajaj group office was located in Wardha. He did earn money during his Bajaj days, like a capitalist, but he became trustee of his wealth and decided to give up further earning of money after he had crossed 50.

Over the next four decades, he donated generously, supporting the cause of the education of girls and even donating substantially to the very institute he was presiding. A true Gandhian to the core, Dhirubhai strove consistently to bring in the timeless principles of the Mahatma in the boardrooms of the corporate world and conference rooms of leading NGOs.

Dr Sushila Nayar, the founder President of Kasturba Health Society and Director of Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Sevagram, was running a medical school in Sevagram. Although the central and the state governments took care of three-quarters of the budget, Dr. Sushila Nayar found it difficult to raise her own share—25%—year after year.

In 1982 Sarla Parekh, the Mumbai based founder trustee of the Kasturba Health Society introduced Dhirubhai to Dr Nayar and suggested she use his financial wizardry in managing the medical school. Dr Sushila Nayar saw Dhirubhai’s role to help her in the progress and development of the medical school and requested him to join the board of the Kasturba Health Society, an offer he gleefully accepted. He started devoting his substantial time for the institute.

In 1986 Dr Sushila Nayar offered him the post of vice-president.

When he joined, MGIMS was run on a modest budget of 80 lakhs per annum. Dhirubhai brought his financial expertise to Sevagram, managed the cash flows, and helped the institute not only with a solid financial group. Over the course of 40 years, under his guidance, the KHS budget grew substantially to 240 crores.

In the late nineties, following a heart attack, Dr Sushila Nayar gradually handed over all responsibilities of managing the organisation to Dhirubhai. Seen as an heir apparent to Dr Nayar, Dhirubhai ensured that the medical school didn’t deviate an inch from the principles laid down by his mentor.

“In 1982, when I arrived in Sevagram, I couldn’t even spell or pronounce half the names of the hospital departments,” Dhirubhai would often humorously remark, showcasing his self-deprecating wit. He quickly learnt the intricacies of the job and in the Nehruvian mode, brought distinguished academicians on the board of Kasturba Health Society, asking them to play an active and meaningful role in spreading scientific temper in the institute. He was instrumental in bringing Dr Manu Kothari, Ashok Vaidya, Dr Gupta, BS Chaubey, GM Taori—to name just a few—on the board of Kasturba Health Society.

Dr. Sushila Nayar passed away in January 2001. The governing body of the Kasturba Health Society unanimously elected Dhirubhai as the president of the Society soon after. Dr. SP Kalantri, professor of Medicine at MGIMS, who had good fortune and privilege of working with him for four decades, wrote in the institute’s 2001 bulletin, “At a time when the medical schools in the country are going through a serious financial crisis and are being accused of producing masters of mediocrity, Dhirubhai faces a tremendous challenge. He has to uphold his mentor’s distinguished legacy and fulfil her dreams. We only hope that he upholds the bright torch of the MGIMS “aloft, undimmed and untarnished” and ensure that its light reaches the poorest of the poor.”

Dhirubhai stayed true to these ideals. Neither the commercialization of medical education, nor the proliferation of medical schools in the country, nor the expansion of private for-profit hospitals in the vicinity of Sevagram could deter him or lead him astray from his principles.

Dhirubhai adhered to the organizational ethics to the hilt—ensuring fairness, honesty, transparency, efficiency and displayed zero tolerance for corruption. He had people working for him, but he had a tight rein on every part of the process.

“All I want is for MGIMS to provide top-notch education and healthcare that’s accessible to all,” he would summarize his philosophy in a straightforward statement.

Under his leadership, MGIMS completely unlinked itself from the sponsorship of drug industry, successfully ran a low-cost drug initiative in the hospital, and introduced various essential initiatives. The list includes a hospital information system, a unit for adopting newborns of unwed mothers, trauma centers, medicine department buildings, ICUs, a Cath Lab, dialysis units, alcohol and drug de-addiction centers, a mother and child center, and a palliative care center. He also oversaw the construction of numerous hostels for medical students and residents.

Dhirubhai’s passion for public health was evident in his nurturing of the community medicine department, where he encouraged innovation and supported the implementation of new ideas and concepts.

Melghat, nestled in the Satpura mountain range in Maharashtra, is home to the Korku Adivasis. The villagers faced limited healthcare access and poor infrastructure, with malnutrition-related deaths often making headlines. Recognizing this urgent need, Dhirubhai Mehta and Mr. SR Halbe, his associate and a family friend, established a healthcare center. They secured full support from MGIMS, urging residents, physicians, and nurses to devote themselves to serving this underserved community, reflecting their dedication to addressing injustice in healthcare.

Dhirubhai also made a point to personally visit the center. During these visits, he offered hope, encouragement, and moral support to its healthcare workers, further solidifying their commitment to improving healthcare access in Melghat.

Never one to mince words, Dhirubhai Mehta fearlessly expressed his views, unafraid of the repercussions. He was known for his courage in speaking truth to power, never hesitating to call out injustice or hypocrisy.

During the tumultuous 20 months of the national emergency, declared on the night of June 25, 1975, a pall of gloom descended upon the nation. The citizens felt shocked and stirred. Throughout this period, an eerie silence prevailed. Individuals offered praise to the rulers of the Emergency regime. Civil servants, when asked to bend, crawled without hesitation.

While still employed at Bajaj Auto, he boldly opposed the state of emergency enforced by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. This was a courageous stance, considering his full-time corporate responsibilities, yet he fearlessly stood against what he perceived as a threat to democracy.

In the midst of these challenging times, when Jayaprakash Narayan (JP) was diagnosed with chronic kidney disease and transferred from PGI Chandigarh to Bombay’s Jaslok Hospital, Dhirubhai was actively working with the Bajaj group. Despite the looming threat of arrest, Dhirubhai and his wife, Nandini, showed remarkable courage by faithfully visiting JP at the hospital, providing him with food, books, and their time. In those days, JP was regarded as the most “dangerous man” in India by Indira Gandhi’s regime. Despite the risks, Dhirubhai stood in solidarity with JP’s cause and took proactive steps to raise funds for the movement, undeterred by potential consequences such as job loss or arrest.

In that era, he considered JP as the conscience keeper of the country. Until JP passed away on October 8, 1979, Dhirubhai and Nandini became a part of their extended family. Dhirubhai fully supported him, funding his causes and taking care of the organisation.

He threw himself into the activities of the JP movement with unmatched zeal and passion. He stood among the throngs supporting the JP movement, fearlessly raising slogans against the emergency. He shuttled between Patna and Mumbai, fearlessly confronting those who opposed the movement.

Nandini and Dhirubhai went above and beyond, assuming the key role in organizing JP’s daughter’s wedding—Janaki wedded Kumar Prashant—where they not only facilitated the sacred ceremony of Kanyadan but also shouldered the responsibility of ensuring every detail was meticulously attended to, symbolizing their steadfast support for JP’s cause and their deep personal connection to his family.

Dhirubhai was also a long admirer of Vinoba Bhave but was disillusioned by Vinoba’s tacit support of emergency, which he called Anushasan Parv. Dhirubhai didn’t hesitate to take cudgels for JP’s movement and wrote strong letters to Vinobaji arguing that his support to the emergency was inexplicable.

Dhirubhai was closely associated with several trusts, including the Kasturba Health Society in Sevagram, the Saurashtra Trust, The Janmabhoomi Group in Ahmedabad, Swami Shivananda Eye Hospital in Rajkot, Kasturba Gandhi National Memorial Trust in Indore, Gandhi Peace Foundation in Delhi, Gujarat Vidyapeeth in Ahmedabad, Navjivan Prakashan in Rajkot, a hospital serving tribal population in Melghat, and Gandhi Memorial Leprosy Foundation in Wardha. He dedicated his time, effort, and funds to support these Non-Governmental Organizations. Unlike many trustees who merely hold the title, Dhirubhai approached his trustee roles with incessant commitment and dedication, a rare quality in today’s context.

Kind, loving, funny, and always thoughtful of others, Dhirubhai knew how to encourage and boost the morale of those who worked in adverse settings.

Dhirubhai had a tendency to have strong likes and dislikes. As one who always trusted his intuition over objective assessments, he once famously said, “Don’t try to confuse me with data. I have already made up my mind.” Indeed, all during his Sevagram days, he earned the reputation of being a quick decision maker, sometimes throwing caution to the winds.

“I love to take risks in life. And my intuitions and risk-taking ability have paid off, most of the time,” he once remarked. His willingness to embrace risks reflected his confidence and adventurous spirit, leading to many successful endeavors throughout his life.

He had a deep love for literature, delving into works in both English and Gujarati. While Gujarati was his native language, he expressed his thoughts in English. Each morning, he would begin by perusing half a dozen English and Gujarati newspapers, and as the day progressed, he eagerly absorbed Gujarati poems, dramas, novels, and historical texts.

Amidst his busy schedule, he actively monitored the stock market. Remarkably versatile, he effortlessly moved between the spiritual guidance of Makrand bhai and Murari Bapu from Gujarat, the corporate world, voluntary not-for-profit organizations, and the Bombay Stock Exchange, displaying remarkable dexterity as he shifted roles.

In February 2016, he teamed with Mr Sheshrao Chavan to author a 551-page book “Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel- A Man of Few Words and Many Triumphs”. He also wrote hundreds of articles expressing his view on different matters of national and social importance. His articles always carried his frank viewpoint on many financial and political decisions.

On August 14, 2022, Nandini, Dhirubhai’s wife, passed away at the age of 80 after battling diabetes and high blood pressure for years, which eventually affected her kidneys. When her kidneys failed and she required dialysis, Dhirubhai arranged for her to receive treatment at home instead of spending hours in the hospital three times a week, ensuring her comfort during the process, which lasted for a year and a half.

Nandini, a talented poetess with a profound understanding of Hindi literature, chose not to live in the shadow of Dhirubhai’s accomplishments. Instead, she published several acclaimed books and shared her poems on various life themes across the country, establishing her own identity. Her passing marked the end of their 56-year partnership and deeply affected Dhirubhai, leading him into a brief period of loneliness.

Despite facing personal challenges, he made sure to attend all meetings, both in Sevagram and Delhi, to keep the institute running smoothly.

Sevagram held a special place in Dhirubhai’s heart and soul. Just a fortnight before he pased away, he had visited Sevagram and actively participated in all administrative decisions. His wife often remarked that he lived and breathed Sevagram every day of his life. In the final stage of his life, nothing mattered to him more than Sevagram medical college.

After his wife passed away, even though he lived alone in his spacious apartment on Laburnam Road in Mumbai, tended to by dedicated staff and his loving daughter who lived nearby, he chose not to relocate to Sevagram. Despite the better accessibility of health facilities and the chance for increased interaction with loved ones that Sevagram offered, he stayed rooted in Mumbai. Perhaps, the spirit of a true Mumbaikar ran deep within him, keeping him tied to the city he called home.

He dedicated his thoughts and efforts to preserving the tradition and culture of the institute he had been associated with for four decades.

Since its inception, MGIMS has had a tradition of requiring all first-year medical students to spend a fortnight in Gandhi’s Ashram shortly after their admission. Here, they learn medicine under the guidance of their teachers while also imbibing the values of self-reliance through practical tasks such as sweeping floors, washing clothes, cleaning utensils, and attending prayer sessions at 5 am. Additionally, they learn the art of spinning yarn, a skill advocated by Gandhi. Dhirubhai took a keen interest in these activities, often engaging in free sessions with the students to discuss the relevance of Khadi and Gandhi in modern times. During these interactions, he not only addressed their questions but also gained insights into their unspoken concerns and needs, particularly those who were unfamiliar with village life. He also attended social service camps alongside the students, where they stayed in dormitories in villages. Here, he freely mingled with the students, joining them for dinner and providing guidance, which he took great pride in sharing at social gatherings.

During his frequent visits to Sevagram, which occurred nearly every month, he made it a routine to tour the entire campus during his 5-kilometer walk. This allowed him to observe firsthand the developments on campus and stay attuned to the pulse of the institution. At the crack of dawn, he would open his doors to the staff members of the medical college and hospital. People would come in with their concerns, grievances, and personal matters, finding in him a patient listener who tried to assist them as much as he could.

Some visitors took advantage of his openness, exploiting his kindness for personal gain. Despite being aware of his vulnerability to flattery, Dhirubhai remained accessible to all, leaving his doors open to anyone in need. “I must know why they knock,” he’d often say, showing his commitment to addressing everyone’s concerns in the institution.

“In our quest for greatness, Sevagram must not stop working hard. Let’s come together to embrace new ideas, use technology, and build more facilities to make sure everyone in our community can access healthcare,” he would passionately advocate, repeating his vision in every meeting, year after year. In the twilight of his life, mindful of his failing memory and physical strength, he often lamented, “If only I had more energy, I could have realized many more dreams for MGIMS.”

Despite his sincerity, dedication, and intelligence, Dhirubhai had his share of weaknesses. He enjoyed name-dropping, often boasting about his associations with ministers, prime ministers, and governors. His continual recounting of his closeness to Sharad Pawar bordered on excessive. This vulnerability to flattery and sycophancy made him susceptible to exploitation.

He was a victim of “I, me, and myself syndrome,” earning him the sobriquet of “I specialist” from his colleagues.

His weakness for food was well-known on campus. Faculty members capitalized on this, personally delivering home-cooked breakfasts and meals tailored to his Gujarati taste buds.

Dhirubhai also struggled with strong-willed individuals who refused to conform to his directives. Shailaja Asawe and Vibha Gupta, both considered for the position of Secretary of the Kasturba Health Society, declined because they wanted to work independently.

As he aged and his memory declined, Dhirubhai stubbornly clung to his position as the president of the Kasturba Health Society, despite losing the ability to effectively manage the organization. He would spend hours in his office with administrative staff and management personnel, yet failed to make any decisions. Instead, discussions would veer off-topic into personal stories and anecdotes, leading to a paralysis of decision-making and organizational problems.

Even as his memory faltered, he resisted grooming a successor or delegating authority, creating awkward situations in board meetings.

This pattern persisted at Sevagram, where Dhirubhai struggled to identify or mentor a successor. In board meetings, despite his wit and courtesy, he maintained a tight grip on power, discouraging discussions, debates, or dissenting opinions.

During my frequent interactions with Dhirubhai, I discovered another aspect of his life: his deep religious devotion. He dedicated an hour each morning and evening to performing Puja, and whenever he was in Sevagram, he made it a point to visit the Goddess Durga temple in Wardha every day. Standing before the idol in the temple for nearly 15 minutes with closed eyes and a serene expression, he would offer his heartfelt prayers to the Goddess. “I owe everything in life to Amba Mata,” he would often say. “I am because she showers incessant blessings on me and stands by me through thick and thin.”

This deep faith and trust in God, coupled with a strong belief in fate, stood in sharp contrast to his personality. Despite his reliance on divine guidance, he also saw himself as the master of his own destiny, taking responsibility for all his actions and their consequences.

On Saturday, April 20, Dhirubhai was admitted to the Bombay Hospital for what was presumed to be viral pneumonia. Forty-eight hours later, today, on April 22, he passed away peacefully, with his son Nirad and daughter Maitry by his bedside.

Dhirubhai dedicated four decades of his life to Sevagram, tirelessly striving to ensure that the institute maintained its position at the forefront of healthcare in the country. He refused to compromise despite the temptations of privatization and profit-driven medical practices.

His commitment and integrity set a standard that will be challenging to match.

As we bid farewell to a multifaceted talent, we are reminded of the immense impact he had on Sevagram and the countless lives he touched through his selfless service. His departure marks the end of an era for Sevagram, yet his legacy will continue to inspire and guide us in the years to come.

It’s really difficult to write about a person who had donned so many hats,(or caps). His lifelong association with Bajaj family and Wardha must have promoted him to be a part of mgims. You have given a quite balanced description of his life and actions. But it was expected from you.

Great 😃

Great personality and truly dedicated. Dhirubhai ji lived on Gandhian values and continued to take MGIMS to new heights. Yet very simple and approachable. Nice to know many of his unknown life history and work through this beautiful narrative sir.

Sadhana Bose

Om Shanti🙏🙏An era has come to an end…. It was a well lived life and may his soul have a peaceful onward journey. It is interesting to learn about the young, aspirational Dhirubhai. He must have been around 52 yrs old when I met him for the first time as a protesting student.

Fast forward to 2008 when he was visiting his daughter in UK. The same Dhirubhai and his very hospitable wife Nandini ji looked after us with so much love when we visited them. They hosted us for dinner that was prepared by Nandiniji…..and we were gifted a poem she had written.

Shraddhanjali 🙏🙏

May his personal family members and all at MGIMS have the strength to move ahead after experiencing the grief. Such stalwarts leave a huge imprint

🙏Om Shanti 🙏 Deepest Condolences 🙏 Thank you Dr kalantri Sir for such detailed Obituary many of the things we never were aware of

Immensely sad to realise this, he always supported modernisation of the institute and upgradation to acquire latest technologises.Sincere condolences to whole family and Mgims too

Sir, feeling nostalgic. Closing this chapter with inspiration and gratitude, and bracing oneself for new begining.

I’m really in shock sir. This is an unbearable loss. Now,there is a feeling of loneliness and lost in deep ocean. Time will say on what path is chosen by our KHS / MGIMS family, but journey is difficult.

Detailed write up on Dhirubhai’ s life including work at MGIMS, Sevagram. His contribution to teachers timely promotion and providing many other facilities has helped Sevagram college retain its staff. Om Shanti.