In the late 1960s, a young man stepped off a dusty bus in Sevagram. Tukaram Sitaram Gawande had traveled over 200 kilometers, seeking relief from a stubborn fistula. Kasturba Hospital, known for its Ayurvedic treatments, offered hope. The cure worked. But Sevagram offered something more. He stayed.

Fate, however, had its own script.

In April 1970, Dr. B.C. Harinath arrived at the MGIMS, India’s first rural medical college. Fresh from the United States, where he had earned his PhD in chemistry, he was appointed head of the Biochemistry department. During his time in the U.S., he had formed a close friendship with Dr. Atmaram Gawande, a urosurgeon who had migrated there in the early 1960s. Harinath knew him well.

Settling into his new role in Sevagram, Dr. Harinath was surprised to stumble upon a peculiar connection—Tukaram Gawande was the nephew of his old friend Atmaram Gawande.

Dr. Atmaram Gawande was no ordinary doctor. Originally from Umarkhed, a small town in Yavatmal district, he had built a distinguished career in the U.S. But his influence extended beyond medicine. He was a close confidant of Vasantrao Naik, Maharashtra’s longest-serving Chief Minister. Naik, who hailed from Pusad, a neighbouring taluka of Umarkhed, shared a deep friendship with Gawande. Whenever Naik visited the U.S., he made it a point to meet his old friend. Their conversations stretched late into the night over endless cups of tea—and cigars.

Amused by the strange coincidence, Dr. Harinath wasted no time. He offered Tukaram a job as a technician in the Biochemistry department. And just like that, a man who had once arrived as a patient now found himself at the heart of a laboratory poised for groundbreaking research on filariasis.

Then came the day that left everyone bewildered.

It was the late 1970s. A sleek government car rolled into MGIMS, and out stepped Chief Minister Vasantrao Naik. After exchanging pleasantries with Dr. Sushila Nayar—the founder-director of MGIMS—he made an unusual request.

“Can I see Tukaram Sitaram Gawande?”

Dr. Nayar blinked. Who? There was no faculty member by that name. A flurry of inquiries followed until someone finally pieced it together—Tukaram was a technician in the Biochemistry lab.

Summoned, Tukaram arrived, unassuming as ever. What followed left the assembled professors and administrators speechless. The Chief Minister of Maharashtra sat across from Tukaram, listening intently, his expression warm with familiarity. For ten minutes, he asked questions, cracked a joke or two, laughed heartily, and, as if settling into an old habit, asked for tea to be brought for them both—unbothered by the puzzled glances around him.

That was the world then. A Chief Minister could hold a conversation with a laboratory technician without pretense. A chance illness could turn a stranger into a scientist. Fate could tie together a humble man from rural Maharashtra with a world-famous surgeon in America.

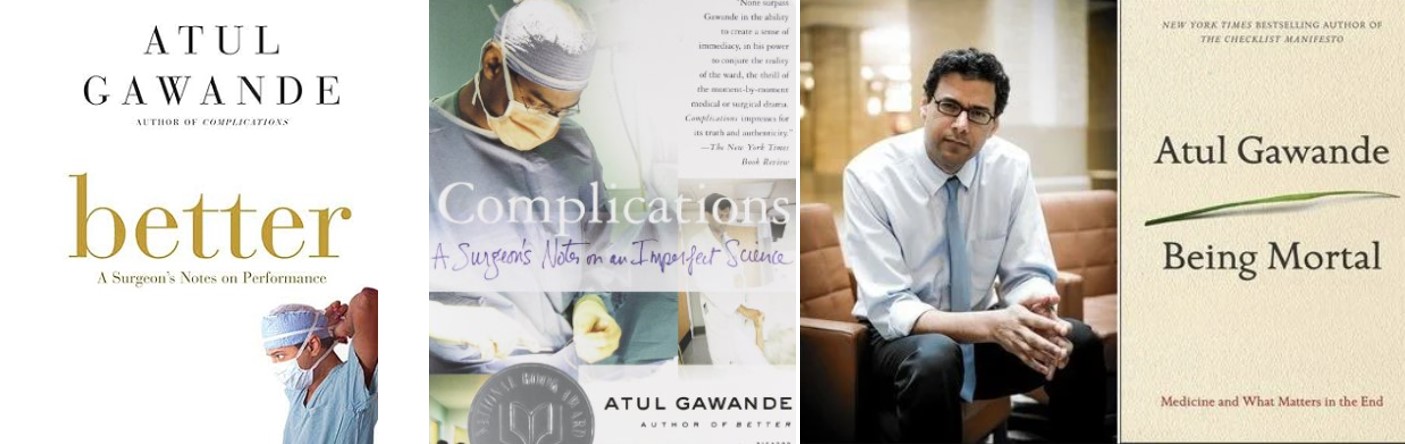

Years later, Tukaram rose to become the Biochemist of the MGIMS lab. Eventually, he, too, left for the United States, drawn by new opportunities. His nephew, Atul Gawande, would go on to become one of the most celebrated medical writers of his time, authoring Complications, Better, and Being Mortal. He would advise U.S. Presidents on healthcare and lead global public health initiatives.

But back in Sevagram, in the corridors of the Biochemistry department—where Tukaram Gawande once assisted in pioneering research on microfilaria—his legend lingers.

What a knack you have.i have said this before and it is as true today. Medicines gain is literature’s loss.