When Dr. Kush Kumar first walked into Sevagram in the blistering summer of 1976, conversations stopped mid-sentence. He was hard to miss—tall, broad-shouldered, eyes probing behind thick spectacles. His English was flawless—precise when he spoke, elegant when he wrote. On rounds, his questions made residents squirm. In the OR, he moved like a man in full command. He read X-rays like a poet reads verse—slowly, and between the lines.

He had come from the plains of Uttar Pradesh, trained at the prestigious King George Medical College in Lucknow, and earned his MS under the legendary Dr. Tuli in Banaras. A PhD in orthopaedics would come later. But in Sevagram, he was simply Doctor Sahib—the new face in a struggling department.

Orthopaedics then was skeletal—thirty beds, a wheezing X-ray machine, a forgotten corner in the OPD, where Paediatrics now stands. Together with Dr. S.C. Ahuja, he gently petitioned for a shift. They got a new space near surgery, borrowed benches, hung a board, and called it home.

Then he left.

Six years passed. In November 1982, he returned—not as a visitor, but as Head of the Department. Older. Calmer. Sharper. He stayed five years.

He could listen to a limp and hear its story. Ask the MGIMS batch of 1975—they remember. He nudged Dr. Madhu Kant toward the forgotten feet of leprosy patients and encouraged Dr. N.K. Kapahtia to study the twisted legs of children with polio. “Feet speak too,” he once said, half-smiling. “You just need to learn their dialect.”

But it was spinal tuberculosis that claimed him. Trained under Dr. Tuli, he understood its slow destruction, the silent resilience of patients, the thin line between healing and helplessness. He didn’t chase TB. He studied it with reverence.

He had a photographic memory. He quoted textbooks with ease, delivered talks laced with humour and wit. But in 1991, he surprised everyone. He sketched.

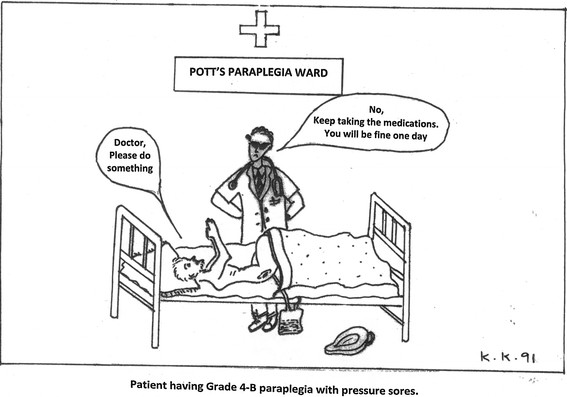

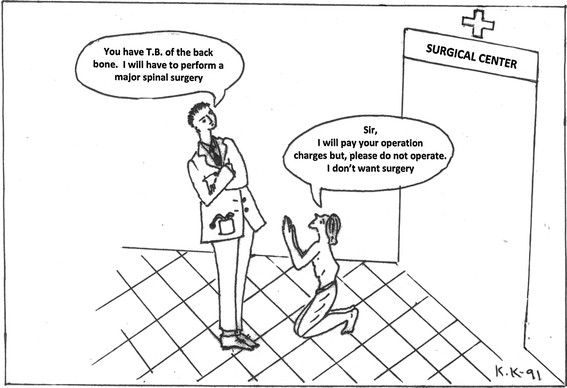

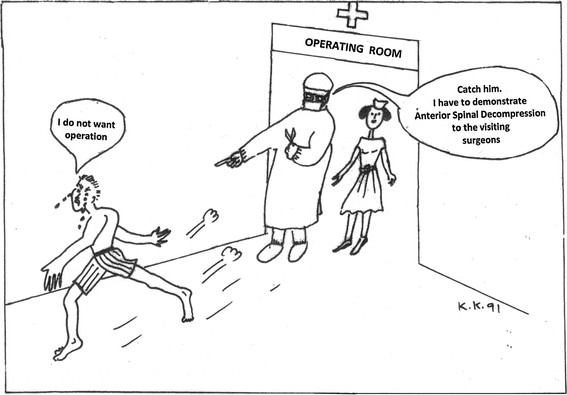

Three drawings, signed “KK.” Not diagrams—portraits. TB of the spine, seen not just in vertebrae, but in lives. A child’s stoop. A mother’s worry. The gulf between prescription and poverty. A satire on medical ethics. These weren’t illustrations. They were insights.

In 2017, those sketches resurfaced—featured in a review article on spinal tuberculosis he published from the USA. The lines had not aged; they still spoke with quiet urgency.

He left Sevagram in 1987, subsequently working at two medical schools in India: Karad and Dehradun. He also held positions in Iran, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Trinidad and Tobago, Malawi, and Zimbabwe. And finally, the United States—where he passed away in 2020, struck by a cruel irony: a tumour in the organ he cherished most—his brain.

His wife, Vibha, left her own legacy—feeding protein-rich laddus to children in Anji for her 1985 MD thesis, guided by Dr. M.P. Dwivedi.

And now, in quiet hours, the orthopaedic OPD sometimes seems to pause—as if waiting for the scratch of a pencil, sketching the silence between pain and healing.

डॉ कुश कुमार के विषय में संक्षिप्त पर संपूर्ण विवरण पढकर अच्छा लगा।

Wonderful write up on Dr Kush Kumar. He was quite a charismatic personality and fitted the then stereotypical orthopaedic surgeon personna. He introduced some novel practices both on the ward and operation theatre. Amongst other things he was interested in cricket as well and had a sharp eye. I remember one incident when he had come to watch a cricket match. I was batting on my usual no. 6-7 down slot. After scoring a lucky quick fire 50 with a few sixes and fours ( and breaking a newish bat down to poor technique and much for Mr Tupkar’s annoyance) I got out and came back to the tent. Dr Kushkumar observed me walking back and as I sat down, with my pads still on, he remarked, “ you are wearing your pads the wrong way round, no wonder you score in boundaries.” I looked puzzled at his remark. He explained that the buckles for the straps on the pads should be tied on the outside and not inside otherwise they will hinder running. I was embarrassed at my rookie error but he smiled and said “just deal in sixes and fours and save your breath for your bowling run up”.

It was nice to read about Dr Kush Kumar. Thanks for the interesting write up on him. I have clear memories of him and Vibha Mam.

Short, stocky, square faced , thick spectacled , piercing gaze and excellent command on English language and his speciality, Orthopaedics. I ( 81 batch) very vividly remember him.

He was very good teacher, ortho department is only where beds are alloted to undergraduate students, we are asked for morning rounds. One dialogue still I remember, those pts extra talkative, he used to ask, Moo band Karo Nak se sans Lo🙏

I had a brief encounter with him when he came looking for Gujar for getting some slides made. I was helping Dr Chaudhary in a dog experiment. I was not using gloves and he reminded me of contracting infection. After getting introduced to him and he knowing that I did my PG from KGMC, had frequent talks. He had a sketch in his hand that day and showed me, it was Krishna correcting hump of a lady. He was getting it transformed in slide for a talk on spine surgery.

Only one word -“Excellent” write up.

He was an excellent teacher and surgeon. He had many innovative ideas bubbling in his mind.

While I imbibed the spirit of Orthopedic from my father, Prof Kush Kumar with Dr Kapahtia and Dr R Srivastava taught us everything else about the subject during the x-ray reading sessions, clinical meetings and Seminars on various important topics.

During the ward rounds his sharp eyes and superb intellect never missed anything. Nothing short of 100% efforts from us Residents would satisfy him.

Above all, he taught us to have confidence in our capabilities.

What a lovely description. My wife Dr Suneela had spoken to Dr Vibha who is now based in DC.

I remember very vividly when their eldest child had lactose intolerance & he was shifted in Soya milk by madam Chaturvedi. He became huge very soon.

Dr Kush Kumar also taught me how to correct pulled elbow when my son had it.

Thanks Dr Kalantri, keep writing & mesmerising us👌

Great Teacher. He had tomato coloured Maruti 800 car.