I call her Badibai—the elder mother! Ever since I was born, she treated me with so much love that she richly deserves this name.

Badibai was born in Barsi, a town in Solapur district in Western Maharashtra, on 26 February 1942. As was the custom those days, she was delivered at her nani’s home. The delivery was protracted and prolonged and Bai had to endure considerable labour agony before she delivered. Six months after Asha was born, the nation would see Quit India movement launched from the very city she lived—Wardha.

Education

She went to a Hindi Medium School opposite Bajaj Electricals, Wardha for her first to third standard. In 1950, Bhaiji realised that if she continued in Hindi medium, she will have to go Swavalambi Vidyalaya, a co-ed school. He didn’t like the idea of his daughter going to a co-ed school. So, in 1951, she moved to Kesrimal Kanya Shala, a Marathi medium school, where she studied until 10th standard. Little did she realise then that this school would become her home after a decade!

Even today, seven decades later, Badibai could accurately recall her neighbours. “I used to play with Bimla Saraf, Sapna and Kanta (Satyanarayanji Goenka’s nieces); Shanta (Udaikaran Jhabak’s daughter who used to work at Fattepurias) and Om Tibdewal (Purnamalji Tibdewal’s daughter). Bedekar and Meghe Guruji used to come home to give tuitions to the boys; girls didn’t have this luxury,” Badibai recalled her initial days.

Badiabai was good at Arithmetic—she scored 20 out 20 in the tenth standard but had no clues when it came to Algebra. She carries these skills even today. ” Mummy is very good at numbers. She can accurately recall the money she owns, her bank balances, her investments and her FDs,” Archana says. So, in the tenth standard her Algebra weakness let her down—she failed to clear the board exam. Bhaiji was also very keen that she also took Sanskrit, Music and Maths—the three subjects that didn’t appeal to her.

She never had the chance to study more and build her career and prove herself but derives genuine happiness from the achievement of her children and grandchildren.

Those days, girls aged 12 and beyond would wear a Sari in school, Badiabi was no exception. Today, it might look very odd to see a schoolgirl in 5th standard going out, and wearing a Sari, but in the fifties, those were the norms.

In 1959, Asha also did Kovid from Rashtrabhasha Prachar Samiti, a popular Hindi examination equivalent to the Higher Secondary Certificate. “Although I was very fond of embroidery, Bhaiji disliked it. ” Why are you spoiling your eyes doing this work,” he would often shout. I quickly became skilled in the art of embroidery and made so many Saris. I also taught these skills to Pushpa.

” I was least interested in cooking. All that I knew before marriage was making daal and chawal. Yet, my mother-in-law was greatly pleased to learn about my limited cooking skills. The 63-year-old mother-in-law didn’t know how to cook! After my marriage, I acquired skills in cooking. There were cultural differences. Compared to Wardha where we used to roll thick rotis, here the rotis were wafer thin!” she recalled.

” Ashok was very dear to Bai. Dwarkadas Gandhi (our buaji’s son) used to call her Bai’s necklace. But Bhaiji used to shower his love on daughters. When SP was born in August 1957, Bhaiji bought a Rs six-and-half Silk Sari for me, Badibai remembered.

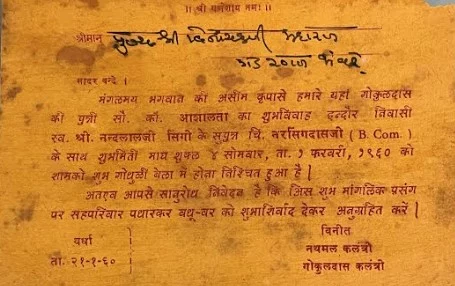

Asha marries Narsingdas in 1960

As was the tradition in the fifties, Bhaiji wanted to marry her off quickly. She grew tired of dozens of families who would arrive in the Marwadi Mohalla to see her. So, when finally Singhis from Indore and Gadarwara came to Wardha and Bhaiji arranged a formal girl-seeing program, the exasperated Asha, when asked how much she had studied, bluntly told them ” Matric fail”. Her honesty touched the hearts of the Indore party and they appreciated her for not letting the lie distort the reality.

The matchmaking proposal came from Shri Madanlal Soni from Nagpur, whose brother-in law Hemrajji Rathi used to live in Wardha.

Narsingdas was a 27-year-old boy then. He had yet not graduated, but had cultivated fine taste in language, music and sports. A day after the engagement ceremony, he was to board a train from Nagpur to Indore via Wardha, Bhusawal and Khandwa. Bai expressed a desire to see him at the Wardha station. Although formally engaged, the young man hadn’t seen the girl he would be marrying. Accompanied by Bhaiji, Pushpa, Yelakeli wali Buaji and Shri Kisanlalji Rathi, Bai waited in the waiting hall of the Wardha station. She garlanded her would-be son-in-law and presented him a flower bouquet. Mr Rathi introduced the Kalantri family to Narsingdas. He mistook his mother-in-law for Asha and loudly voiced his concern—how can I marry a girl who looks like a mother of three children? It took some time, a series of explanations, and a letter from Wardha to steer him off doubts. Finally truth dawned on him that he had mistaken his mother-in-law for his would-be-wife!

The wedding took place on Vasant Panchmi, first February 1960. Bhaiji had made meticulous plans to create an event which would become the talk of the town. “I would do a first class arrangement if you limit the number of Baraatis to fifty; a second-class arrangement if they are between 50 and 100. But be prepared to endure a third-class arrangement if the number exceeds 100,” he sternly warned the Singhi family. So, as the dawn cracked on the first of February, fewer than fifty Baraatis arrived by a bus from Indore. They were accommodated at Bajaj Wadi—the very place where once Nehru, Patel and Bose lived during the freedom struggle. Uttambhau, Professor Ram Krishna Vora and Mira bai Mundra took the charge of the Baraat. The baraatis were served three sumptuous sit-down meals during their Wardha stay; each time the arrangement, the meals,and the decorations changed. Eleven teachers from the Mahila Ashram school, decked in white khadi sari served the baraatis. There was no band nor a baja; instead, a shehnai would serenely fill the background. No baraati was served cut fruits; instead, fresh fruits were kept with a spoon, a knife and a fork.

Chimanilalji Shastri, Bhaiji’s trusted Pundit performed all wedding rituals. Bhaiji strictly wanted to complete the wedding ritual in an hour, which he did. The wedding took place at Godhuli Bela— when the cows return home—and was attended by a large audience.

Tukdoji Maharaj, the much-adored spiritual saint of Vidarbha, graced the wedding ceremony and sang a Bhajan. Shri Chiranjilalji Badjate gifted Gandhiji’s books to all baraatis and Tauji gifted them a silver glass, costing Rs seven apiece. Bhaiji had asked Tauji to get gold ornaments worth 15 tolas from Khamgaon for Badibai. She was gifted a necklace, bangles, earrings and a Mangalsutra on the occasion of her marriage.

I was surprised to know that only Ambu (Amritlal Mundra) mamaji came from Barshi for the wedding. He was accompanied by Bai’s mamaji from Bagalkot ( Karnataka)—Gopi Kisanji Kasat. It’s a mystery why Bai’s parents didn’t attend the first wedding of the Kalantri family ” Their financial condition in the sixties might partly explain their absence,” Badiabi said.

For the wedding, Anusuyabai Bajaj from Wardha (wife of Shri Radhakisanji Bajaj and Bhaiji’s Raakhi sister) had ordered half a dozen Saris from Benares. Of the six Saris that arrived by parcel, two were selected and the rest were returned. A replica of the Amazon order-return era! The two Saris cost Rs 120 and Rs 70 each. Interestingly, Asha wore the red Rs 70 Sari for her wedding ceremony! Jijaji wore a Chudidar Sherwani. He also wore different suits for the three functions held at Wardha.

The wedding turned out to be an expensive affair It cost Bhaiji Rs 13,000. To put that number in today’s perspective, 100 rupees in 1960 are equivalent to 8,584 rupees in 2022. Initially, Tauji had offered that he would cover all expenses but at the last moment backed out. Finally, he shared a third of the wedding expenses.

Post-Marriage Early Days

After marriage, Badibai went to Indore for a year. Those days married women were not supposed to name their husbands. When Bhaiji asked Badibai her postal address, in a plain speak, she said,” Shri ND Singhi. Narsingh Bazaar, Opposite Nasing Mandir, Indore” My father could not help laughing at the number of Narsings in the address! ” Thanks God, the postal address did not include Asha Nursing Home,” Amit jokingly added when he heard the story.

The Wardha and the Indore culture was as different as the Mars from the Venus. The language, the clothings, food, the customs and the rituals differed substantially. Malwa differed so strikingly from Vidarbha! Asha was just 18, and knew no more about cooking than preparing Daal Chawal. Within a year she learned the art of cooking in Indore.

In 1961, Badibai came to Bhopal and lived in the Tapdiya house for the next four years. It was a huge house, and Jijaji was allotted three rooms in the house. Badibai’s struggle began—not yet out of her teens, she had to work from 4am to 11pm, preparing breakfasts and meals for the twenty-odd people in the home and doing all household chores. Although she was perpetually tired and sleep-deprived, she silently endured her misery, never complained, nor even hinted to the parents the amount of work she was made to do. Oblivious of the workload Badibai had to handle on her fragile shoulders, Jijaji was busy working for the Amar Allied Agency, owned by his Jijaji, where he would sale sanitaryware.

Manju, Narayandasji’s eldest daughter, lived with Badibai for a year. She was put in St Joseph Convent where she studied for a year. Eventually, she turned out to be the first graduate girl of the Singhi family. The seeds of her education were sown in Badibai’s home.

” Those were difficult days,” Badibai recalls. Jijaji used to get a salary of Rs 350 per month. I used to supplement his income and eked out a living by doing some stitching work. Once I was put in the AC compartment of GT express that would take me from Bhopal to Wardha. I didn’t have a valid ticket and was asked to get down at Itarsi station. I had not enough money on me to pay for the AC charges. A train TT took pity on me, and walked me to help me board an unreserved third class coach.

“My mother-in-law was strict. But the love between the devrani and the jethani was inexpressible. My Third Jethani was called Sikar wali Bhabhiji and I was identified as Wardha wali. Once I ran out of decent Sarees. I hesitatingly told her my problem. Those days, women were not permitted to go to a shop. My Jethani asked a family friend to discreetly open the back door of a shop when nobody was around. We sneaked into the shop, and did a wonderful shopping— buying beautiful sarees. I was greatly supported by Balkishanji Singhi who would often buy Sarees for me. My other Jethani would fulfil all my wishes. I just had to hint her the things that I needed and she would promptly have them sent to Bhopal from Indore. I came from Wardha—known for harsh summers—and was not used to the biting cold of Bhopal. When my Jethani sensed this, she ensured that every morning Iron buckets carrying boiling water would arrive from Itwaria Bazar to Narsingh Bazar. The bucket would travel a distance of five furlongs.”

In 1980, Om came to Bhopal to learn business from Jijaji. Initially he stayed with her in the Kayasthpura home for a year, and later rented a flat in the Green Colony, Firdous Nagar, Berasia Road, Bhopal. For a year, he lived alone; later Aruna bhabhi joined him. The Chhola Road factory construction was in full swing; Om also used to look after the factory. Two years later, in 1982, he came back to Yavatmal.

Four “A”s arrive

On 23 January 1962, Archana was born in the Matru Seva Sangh Sutika Grih. We used to live in the Bajaj Electricals home then. Those days, the mother and the baby used to be kept in the hospital for 10 days. The delivery was normal.

A year later, Anand was born, on 20 September 1963. He was also born in the Matru Seva Sangh Sutika Grih- we continued to live in the Bajaj Electricals then. When he was eighteen-months-old, he contracted an illness from which he would not recover. “He cannot tolerate cold, and needs to be shifted to a warmer environment,” the local doctors advised. The parents wondered if Wardha could be an appropriate location where Anand could outgrow his illness. Bai agreed to keep Anand, who spent the next eighteen months in the Wardha Bachhraj Press where we moved just before Jiji’s wedding. For him, his Nani became everything and although he would call Asha his mummy, for him she was always a foreigner, intruding into his Nani’s empire. When Badiabi came to Wardha, he would ask when she would go and once, didn’t let him wear Bai’s Sari because it was not hers. He got very attached to Jiji, and would spend considerable time with the staff of the ginning factory, with attendants, chowkidars and milkmen showering their love on him.

Over the four year period, Badibai stayed with Tapdiyas, differences with her sister-in-law began to surface and multiply. She grew tired of endlessly doing household chores and thought that she was reduced to a housemaid. Finally, when the differences became unmanageable, she found a new home for her family—Ramnivas building, Kayasthpura.

The new home—they would pay a rent of Rs 120 per month—was a modest flat on the first floor of a two-story building. The L-shaped flat had three small rooms, a kitchen and a toilet. This home saw Archana and Anand begin their school journey at the St Joseph at Idgah Hills. Jijaji did some background research before he chose the school for his children. Jijaji had learnt that the school was established in 1956 by Mother Ignatius, a Swiss nun. The school was managed by congregation of sisters of St. Joseph of Chambery, Panchmarhi, MP. There were just 12 students when the school started but within a decade it grew into a large school.

Anand was very good in studies, and bypassed the second standard to enter into the third standard. The convent school gradually stopped boys from studying with girls, the reason why Anand moved to the Campion school, a private catholic school that shall also admit Aalok and Amit later. Interestingly, Anand filled the admission forms for Amit and submitted them to the school office. When the school father came to know about this, he was impressed. ” When the elder brother is acting so responsibly, how can I refuse admission to his younger brother,” he openly said. Thus, Amit was admitted to the school without an interview or a test.

The Campion School has an interesting history. In July 1965, at the invitation of the Archbishop of Bhopal Eugene D’Souza, Fr. Emmanuel Ferdinand More, a Spanish Jesuit from Mumbai, established a school which he named Campion School, in honour of St. Edmund Campion, a sixteenth-century English Jesuit, also the patron saint of the school.

Little did Aalok realise that one day he would be invited as the chief guest for the annual function of his alma mater, The Campion School! This was the school where Anand, Aalok and Amit would invite their father to come, ” Because today there is going to be a loud clapping for us.” And their father would never let them down—he would carry and distribute packets of dry fruits to the school children as they would collectively rejoice!

Jijaji was hell bent on educating his children in the best schools Bhopal offered. When his Jijaji ridiculed him for spending on education beyond his means, he shot back that he would rather leave Bhopal than send the children to second-grade schools. Although their financial status was not as sound those days, Badibai saved every penny to invest in their children’s education. The school fees were modest, by today’s standard—Archana would pay Rs Rs 15 for her tuition fees; the one-way would set the pocket lighter by Rs 7. Anand used to cycle 10 km, each side, to go to his school. ” I would compete with the school bus, and would reach school ahead of the bus,” Anand reminisced of his cycling speed. Now I realise that Anand’s car speed owes to the cycling that Anand used to do in his school days.

“When I was interviewed for admission in the third standard, I was asked by the Father of the school what was my hobby? “Sums,” I quickly answered. “No, it is Maths’ ” he corrected Anand. Fascinated by the mystery of mathematics, Anand went deeper and deeper in this subject, and decades later, even when he was no longer a student, he would borrow books from the British Council Library to solve maths problems!

Mrs Gopilal Birla (Ashok Birla’s mother) had secured an admission for Anand, at BITS Pilani. “We were short of funds those days, otherwise Anand would have become a Pilani trained engineer.” Anand dropped out of the first year from Sofia College, Aalok did M COM and left CA halfway through; Archana obtained MA (Economics) and went on to do Material management. Amit added several feathers to his cap—CA, CS, ICWAI, PhD. He became first ever non-medico doctor in our family when he was awarded a PhD on Financial Analysis on Working Capital and Asset Management.

Aalok was born on 11 July 1966 in Sushila Hospital, Indore. Two months earlier, Mamta was born, and Bai was understandably reluctant to have another daughter deliver at her home. So, Aalok was delivered at Indore. When he turned 14, Jijaji conceded to his elder brother’s wishes for adopting Aalok. Interestingly, his mother was not even consulted—tormented by the very thought of her son going away, she refused to eat for a week—when the adoption proposal was accepted. At Wardha, Bhaiji also did not agree to Aalok being adopted by his Tauji. Finally, the wishes of the Singhi family prevailed and Aalok was adopted by Narayandasji, his Tauji.

Adoption was not new for Singhis. This was the fourth adoption in as many generations. Jijaji’s grandfather, father, and he himself had been adopted by the family members, and Aalok followed the suit. Jijaji, born to Manbharibai and Kashilalji Singhi was adopted by Sirekunwar and Nandlalji Singhi.

On 4 September 1971, Amit was born in the Sultania Zanana Hospital, Bhopal. Badibai had asked Bai to be with her for the delivery. Bai agreed and stayed with her for a month.

Archana, Anand and Alok were named by Jijaji. Amit was named by Shri Ghanshyamdas Kabra, Gadarwara.

Sickness and Sevagram

In the summer of 1975, Badibai contracted a genital infection following a gynaecologic surgery. Sepsis developed and she became very ill. Her weight had dropped to under 35 kg. Jijaji brought her to Wardha by car and she was admitted to the Medical College hospital in Sevagram for the next twenty-six days. She hardly ate and required intravenous antibiotics to pull her out. Pushpa, Jijaji and I would stay with her in the private hospital room, located in what is the community medicine department of the medical college. Gradually, surrounded by her family and children, Badibai recovered her health and went back to Bhopal. The hospital billed us Rs 600 for her 26-day stay that included charges for a private room, doctor’s rounds, blood tests, injections and nursing care.

Once, during her hospital days, she looked very sick. Jijaji, thinking that these could be her last moments, began to recite the Bhagavad Gita. Badibai could barely control her anger,” Stop this. I am not dying!” Often Jijaji would turn very emotional and would say,” SP Babu, our kids are small. We need to live just 4-5 years more,” he would say to me in the seventies. Decades later, Amit would often jokingly recall the phrase!

Marriages

In the winter of 1986, Archana married Shri Suresh Mintri (born 28 August 1958). The proposal came from Jijaji’s maternal cousin from Kalimpong. Suresh, accompanied by Mahesh, his brother and father came to Bhopal to look at Archana. The marriage was celebrated at Wardha on 3 December 1986.

Anand married Kirti (daughter of Late Dr Shrikishanji Gattani) from Nagpur on 28 November 1993. This proposal came from Ghanshyam Rathi, our Nagpur-based Bua’s grandson. After Jijaji and Badibai had seen Kirti, Bhavana and I met her at Hotel Temptations, Ramdaspeth where over a cup of coffee we informally gossiped, and cast our deciding vote.

Aalok married Sumita (born, 30 April 1970), daughter of Laxmi and Shyam Sunder Lahoty, on 28 February 1996. The proposal came from Pralhaddasji Kabra, Gadarwara. Aalok, accompanied by his parents and Dagaji went to Delhi and finalised the proposal.

On 23 January 1998, Amit married Pratibha (daughter of Shobha and CA Mahesh Taori) from Nagpur. Pratibha, born on 29 March 1972, had graduated, earning an MBBS degree, from NKP Salve Medical College, Nagpur. Her brother was Amit’s roommate when the two were doing their CA from Mumbai. A chance meeting culminated in love and the two chose to become life partners. Badibai, Jijaji, Archana and Suresh, Kirti and Sumita saw her. They tied the nuptial knot on 23 January 1998.

“I learnt English from my children. I cannot speak the language but can fully read and understand it. We used to ask our kids to learn five new English words a day and use them in sentences. This is how their vocabulary grew and they got a firm grip over the language. I learnt stitching in Wardha and knitting sweaters in Bhopal. Every year she would knit a beautiful sweater and would bring them to Wardha where I used to enjoy wearing them.

Her name Asha is embedded in the names of two of her granddaughters: Pratiksha and Nimisha. They confide in her and she is like a friend to them.

Several children from relatives stayed with Badibai. Narendra Lakhotia and Jagdish, his elder brother, lived with her. Narendra did his second to fourth standard from Shri Jain Shwetamber Higher Secondary School, Bhopal. Jagdish worked as Jijaji’s apprentice between 1977 and 1980. Raju did his 9th and 10th standard from Bhopal. Years later, Tina also spent two years with her—everybody at home taught her. Jijaji would teach her languages; Anand, Maths and Aalok, the rest of the subjects.

Around 2010, Badibai develop severe low back ache. The pains were severe enough to severely restrict her movements. She required a wheelchair to be picked up from the sevagram station when she came to Wardha for a marriage. Her own will power helped her recover completely. We were very surprised when she boarded Dakshin Express to travel from and to Bhopal this November.

“I do not recall a single day when I fought with Pushpa,” Badibai recently recalled. ” Once Pushpa stomped in my room, saying angrily that I want to fight with you. ” Yes, please have a sit. Tell me what the fight is all about,” I asked her. And Pushpa smiled and said,” I have forgotten why I wanted to fight with you.”

” I used to wear gold earrings but Pushpa didn’t have them. So, I gifted a pair to Pushpa. Later, when Bai willed me 10 Tolas of Gold, I passed on the gold to her.”

All her life, Badibai gave the elder sister’s love to Pushpa. She would always understand her pain, her anxiety, the financial problems she would run into or her emotions. She would stand by her, gently pulling her out of the difficulties. These days, not a day goes by, when the two sisters do not talk to each other!

I am amazed the way Badibai has picked up technology. She is often the first one to send birthday wishes on the Love You All WhatsApp group that Archana created and is aware of every happening in the family!

——————————————————————————————————————–

Jijaji

Born in Indore on 30 April 1934, Narsingdasji Singhi, our Jijaji, was 11 of the 12 siblings born to Manbhari bai and Kashilalji Singhi. Three of his siblings passed away. went to a school in Indore.

Education

” Dulichand Sir, our class teacher used to wield his long cane to punish the students seated on a 8 feet long tad Patti,” he recalled the early days.

Next he went to a Maheshwari school and then moved to MS High School, a Government school until his 10th standard. He enrolled himself in the Holkar College as an engineering student. He switched from engineering to the commerce, when his mother thought that an engineer might move out of Indore. Thus, he moved to Jabalpur GS College of Commerce where obtained B Com in 1960. In 1960, when he came to Wardha during his marriage, he was asked by a local Wardha professor which economics book he reads for his B Com. ” I refer to the one written by Professor RK Vora, ” he proudly replied. ” I am that RK Vora,” the local professor stunned him by identifying himself.

True to the family tradition, I too was adopted after I had turned 18 . I made a trust at the time of my adoption to ensure that there are no family disputes for the property.

He owes most of relatives to Jabalpur and Gadarwara in Narsinghpur district, MP. Shri Jagmohandas Malpani, the erstwhile congress minister had come to Indore. His father Seth Govind Das was an Indian independence activist and parliamentarian. An associate and follower of Mahatma Gandhi, he was awarded Padma Bhushan in 1961. Jijaji’s mother asked him to get him admitted to the GS College of Commerce and Economics Jabalpur. Thus Jijaji went to Jabalpur, where for a year or two he lived in a single-seated room in the college hostel.

After B Com, What?

” What did you do after obtaining a B Com?” I asked him. “There were several options, and the list is long,” he warned me. “Are you prepared to hear me out?” he asked me. I nodded. “First, I was offered to become Seth Jagmohandasji’s PA. Second, Seth Narsingdasji Kabra from Gadarwara asked me to pursue law and become a legal advisor. ” I would give you 350 cases a month,” he assured me of a roaring legal practice. Not willing to take the legal profession, I turned down the offer. Third, Balkishanji Malpani wanted me to take charge of the factory. I denied this option too. Fourth, Ashok Birla tried to entice me with an offer for a lucrative job. Fifth, my mamaji from Sikar proposed a job at Chittagong in Bangladesh. My profile would have been to manage a local factory. ” You would get fully paid family leave for two months,” I was about to get enticed, but I refused this offer too. Sixth, Narsingdasji Bangad (my cousin from maternal side) offered to give me a spur yarn agency for Madhya Pradesh.”

Amar Allied Agency

The offers were many—lucrative and promising. But destiny was willing otherwise. Finally, as fate would have it, I came to Bhopal and served at the Amar Allied Agency, owned by my Jijaji Shri Purushottamji Tapdiya. I joined Amar Allied in 1961 and would spend four of my life’s most productive years selling sanitary wares for the agency.

Anand Metal Work is born

In 1965, Jijaji separated from his brother-in-law and decided to try his hand at a foundry that would produce metal castings. He, and later his children, would spend endless hours watching iron getting cast into shapes by melting it into a liquid, pouring the metal into a mold, and removing the mold material after the metal had solidified as it cooled. In 1972, he found a place in Retghat and later at Hamidia Road, near Manohar Dairy, Bhopal. The foundry at Hamidia road began to make manhole covers and tractor wheel weights which he would sell locally.

In November 1980, Anand Metal Works found a new home in Bhopal—Chhola Road. He had bought two plots measuring 7500 square feet in 1975-76 and constructed the factory and his residency atop the factory. Surrounded by quarters of local labour, and Union Carbide facing their factory, they began to focus on the factory. Our old factory, located at Hamidia Road, had to be broken. ” I carried every break of the old factory, and even scrap to the newer one,” recalled Anand.

Anand was just 16 when he entered the foundry business. I thought that I would have to reduce the input costs, if we were to profit. So, I went to all the places where we could get cheap material. I boarded unreserved compartments in the trains to go to Raipur, Rourkela and Dhanbad. I probed the steel plants and explored the coal industry at Dhanbad. Once Jainaryan Pande and I went to Jharkhand and we ran out of money. I had to borrow Rs 100 from a supplier to return home,” Anand described his struggle-filled days. I succeeded in buying raw material at a third of its market price and bought pig iron directly from Bhilai. Soon, our production increased and we started supplying manhole covers, tractor wheel weights and machine components to Indore.

Shail Shikhar

In 1974, Jijaji bought a plot in Karbala near Bada Talab. He had just sold his agricultural land in Gadarwara and reinvested the money. Earlier, the plot was available at a throwaway price of just fifty paise a feet, but the Gadarwara family said No to the proposal. The 7200 square feet plot was available at throwaway price those days—he needed to pay Rs seven per square foot for the plot. Between 1988 and 1990, he constructed a big home where he moved from his Chhola Road factory flat. The home, named Shail Shikhar by Archana, was symbolic of the city that housed the home. The ups and down—Shail and Shikhar—adored the Bhopal city.

In 1995, he acquired a plot and built another foundry at Indore. Aalok went on to handle this foundry and renamed it Mitasha Industries (a hybrid that combines the names of his two daughters—Nikita and Nimisha and mother—Asha).

In 2013, Anand discovered a new location for the foundry. While the Choola unit stayed where it had been all these years, another unit was established in Mandideep, about 28 kms from home. He had to fight a protracted fight with the government before he could own the unit. In the initial phase, when the government didn’t connect electricity, he had to use generators to operate the plant. Boosted by Aaditya—who returned from Manchester to join his dad’s unit—the third unit of the Singhi family is running well. Unlike the previous foundry that ran on coal, this unit runs on electricity and makes high-carbon and steel, this unit is lighter on carbon. On 9 August 2013, when the unit finally started, the Singhi family’s joy knew no limits.

The 1984 Bhopal Gas Tragedy

On the third of December 1984, the chemical disaster took place at Bhopal, the world’s worst industrial disaster. That fateful night, Singhis had retired to sleep. At 1: 30am, they woke up with watering eyes and nose. They began to cough. Anand opened the door of the room and found the entire sky covered by white fumes. He tapped the bedroom door . The first reaction was this could be chills being burnt to show away the thieves. Anand intuitively knew the shape of the things to come. He asked his mother and father to immediately get into the car and leave the home. ” No, we have no time. Don’t try to lock the home, Get down quickly,” he urged and almost forcibly made them step down, get into the car and speed towards Marwadi road. They had two dogs, they chained one and let the other run around. They had no time to release their cows, either. They took one of the guards with them, and Jijaji started driving. December cold notwithstand, the ignition key could start the car in the first attempt. The Premier Padmini, a four-seat 1964 model saloon that they bought in 1972 for Rs 21 000- proved to be their saviour. The car served them well for 31 years—until 1994!

“What we saw was unbelievable. There was a big crowd on the street, People were all around, running amok. We saw people coughing, rubbing their eyes because of severe eye irritation and complaining of suffocation. Papa had trouble driving, because the incessant tears had clouded his vision. From Marwadi road, we went to Bada Talab, and finally decided to go to BHEL campus where Shri Satya Narayan Daga lived. Dagaji was a technocrat and management expert at BHEL. At 3am we tapped his door. He found us dishevelled and distraught. His first thought was that we suffered from food poisoning and were paying for the toxic food that we ate. He couldn’t believe his eyes when we told him the story.

Dagaji had a 5am train to catch. So, papa and I took him to the station in our car. On the railway platform we saw people vomiting, defecating and dropping dead. The entire railway platform was filled with fear, panic and desperation. No train was coming to Bhopal. He returned home with us.

The next day, early in the morning, we went back to our home. Thousands of people had died by the following morning. Mass funerals and cremations were to follow. Trees in the vicinity became barren, and bloated animal carcasses had to be disposed of. Our dog was dead, and so were the cows. The plants had turned black. The gases were blown in a south-easterly direction over Bhopal. The wind direction that day decided the fate: those who were spared the wind, escaped miraculously; those who ran in the direction of the wind, had to face the wrath of the gas.

“Years earlier, one Mr Kabra had visited our home. He told us about the toxic Methyl Isocyanate (MIC) gas the Union carbide plant was manufacturing. He also told us how toxic the gas was. The UCIL factory was built in 1969 to produce the pesticide Sevin using methyl isocyanate (MIC) as an intermediate. An MIC production plant was added to the Union Carbide site in 1979. If the gas ever leaks, it can kill you within minutes, he said. Somehow, I was correctly able to recall his words and could anticipate the shape of the things to come,” Anand explained what made him run away, so quickly.

Music

I began learning violin and harmonium during my Indore days. ” Your violin reminds me of a beggar on the street,” my mother admonished me. I bought a violin—a simple four-stringed instrument played with a bow and hunted for a music master who would come home (in Balkishan Singhi’s room) and teach me how the strings are tuned in. I learnt how to play violin in the North Indian Hindustani style. I also joined another music class. Those days Marathi people in Indore had an ear for music and languages. My class had all girls, and I was the only odd boy out.” He couldn’t become a violin maestro but developed a keen interest in both vocal and instrumental music.

More recently, he started singing Hindi songs of the fifties and sixties. In January 2022, Badibai and he went to Kochi to stay with Archana and Suresh for a month. Archana recorded a 1960 song that he sung in their home—Chaudhvin Ka Chand Ho. A fortnight later, at a family reunion in Sevagram, he sang Tum Agar Saath Dene Ka Vada Karo, a 1967 Humraaz movie song. The audience couldn’t believe their eyes—and ears—to watch a 1934-born man singing the songs, so effortlessly and so melodiously. “Hindi movies and songs fascinated me. I used to go to the cinema theatres on the first day, the first show. My favourite actors were Guru Dutt, Dev Anand and Meena Kumari,” he said. “But almost never did he take me for a movie,” Badiabi said complainingly!

“I also learnt Sanskrit during my school days. My brother Murlidharji Singhi hired a Sanskrit teacher, who insisted that I should learn to recite Sanskrits word, by heart. His love for Sanskrit didn’t surprise me, for Malwa was the centre of Sanskrit literature during and after the Gupta period. The famous playwright, Kalidasa, came from Ujjain. Young Narsing read all his plays—the story of king Dushyanta, who falls in love with Shakuntala; Urvashi conquered by valour; the epic Dynasty of Raghu and Kumarasambhava (“Birth of the war god”), as well as the lyric Meghaduuta (“The cloud messenger”).

Sports

“I played as many games during my school days as I could count on my fingertips. I played volleyball, Table Tennis, Badminton and Cricket. I also used to break sweat in the Akhada where I would do sit ups for muscle building, stamina and strength. I also became a wrestler and could nail the Pehlwan in no time.

“I also tried my hand at shooting and learned Lathi (a long, heavy bamboo stick), a weapon for an ancient martial art.”

Fascination for Ayurveda

Naturopathy and Ayurveda fascinate him. ” I have hundreds of books from Ayurveda, which I carefully read and use that knowledge to make home-based medicines. ” Recently I developed a bad eczema on my leg. Aalok asked me to keep a wet dressing over the eczema for fifteen hours a day. Within a fortnight, my eczema cleared completely, leaving behind no trace. “I have prepared so many Churnas for better memory, digestion and energy,” he says with a twinkle in his eye.

The Home Engineer

Manners and Etiquettes

We always associate Jijaji with immaculate manners and conduct. “Where did you learn all the manners and etiquettes?” I asked him. “I owe this to my Jabalpur days in the fifties. During those days, I closely watched and emulated the table manners, the languages, and the sartorial styles. I was very particular—and am even today—how the food is served, and eaten. Wherever he went to the market to buy fruit and vegetables, he would very carefully choose the fruit—judging the colour, contour, aroma and freshness of the fruit and sizing its price. Even as mundane a task as shifting the car gears was an artistic activity for him— he is very particular the way the fingers grip and shift a gear. His shirt, even in the late eighties, is immaculately tucked in his trousers, and his belt is precisely positioned.

“My manners- the most appropriate word is Tehjib in Urdu, has helped me professionally. My words, my spoken commands, and my conversations would leave a lasting impression on my customers and almost always I would end up winning the contract,” he said.

Jabalpur was not the city of his birth. He didn’t grow up there—he spent just a few years there. Yet, Jabalpur is somehow embedded in his sense of self and language. That culture is reflected in his routine life—be it dressing, speaking, eating, driving a vehicle, knotting a tie or greeting a person. Soon after marriage, when he used to visit Wardha, Bai would be embarrassingly shocked to see her son-in-law greeting her by Salaam Alaikum. She had another surprise in store. He would do her salaam in the traditional Muslim style. In an orthodox Marwari home of the sixties, where elders were paid respect by the younger generation by touching their feet, this departure became talk of the home!

In 2020, he received an electric shock at home. Although it took awhile to have his thumb and injury healed, he was not frustrated by the slow recovery. He switched to the left hand for eating, and continued to carry on without a complaint.

Archana wrote on 8 December 2022: “He is indeed an iron man. His personality is so multi-faceted. Capable of doing diverse things with immaculate ease, he was as much at ease in singing romantic songs, playing violin, playing harmonium, picking up choicest fruits and casting metal in his factory. When it came to studies, he was very strict and disciplined and his standards were exacting. He was obsessed with making his kids learn everything— be it sweeping the home, painting the house, or driving the car. And he demanded precision in each activity he ordered. I was told a story of his youthful days when he prided himself in accepting unbelievable challenges. Once his friends challenged him to put an earthenware pot (matka) atop a woman’s head without touching her while driving a Jeep. They thought that it was an impossible task to accomplish. He proved them wrong and did this act with a superb command!”

Badibai and Jijaji Today

Today, Badibai and Jijaji live in Shail Shikhar, the home they—and their children—painstakingly built 32 years ago. Among other usual stuff, their bedroom is a home to a refrigerator, a television and a tea induction cooktop. This November, when I stayed with them for a day, he made it a point to make and serve me the perfect cup of morning tea. He also showed me the table lamp that he recently made. I was amazed to see its design and beauty. His room oversees his garden. He pees through the large windows of his bedroom to watch the plants grow, flower and fruit. His room has become his empire where he lives without any grudge or animosity. Remarkably articulate and gifted with an envy-provoking memory, both Badibai and Jijaji have defied their age. They exemplify that selfless sacrifice and understanding each other is the essence and soul of the relationship. They were 26 and 18 years old when their arranged marriage was conducted in 1960. Proud to have raised four children and grandchildren who have done so well in their lives, they love and care for them and rejoice in their grandchildren’s success stories. Their warmth and radiant smiles brings so much happiness to the guests.

I was so happy to spend a day with them, as we walked down memory and I documented his memories on the sheets of papers Anand pulled out from his cupboard. ” You have given me fifteen sheets. I will have to fill all of them,” I told Anand. Little did I realise that by the time I left Bhopal, the sheets were full—rich with anecdotes, stories and memories!