Dr K.V. Desikan, a legend in leprosy, passed away on 23rd October, 2022. He was ninety six.

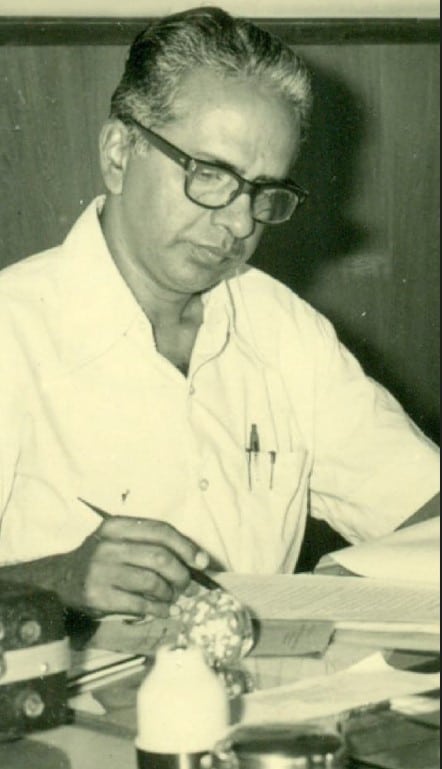

In a career spanning more than sixty years, Dr. Desikan invested considerable effort and time trying to understand the mystery that shrouds leprosy. He began working in an area few others cared about. Leprosy, in the early fifties, evoked considerable fear even among doctors. Trained in Pathology at the Christian Medical College, Vellore, he had an infectious infatuation with Mycobacterium leprae, trying to understand how the pathogen brought so much disability and misery to people. He carried out the largest series of autopsy studies on leprosy patients and devoted his entire life to leprosy related research and field work. Quick to learn the art of multitasking, he played multiple roles: that of a doctor, a field worker, an epidemiologist, a researcher, a scientist and an administrator.

Born into a poor family in 1926 as the eleventh child among twelve siblings, Dr Desikan joined Mysore Medical College in the MBBS batch of 1944. An intelligent student, he was among the very few students in his class, who had made it to the third year without failing any subject in any year. He was indeed an outlier, by the yardsticks of the education system of the day. In 1949, he qualified as a medical doctor. By then, he was deeply influenced by Gandhian ideals.

Having been diagnosed with leprosy himself as a medical student, Dr. Desikan had personal experience of the trials and tribulations that followed a diagnosis of leprosy in those days. Interactions with Dr. Cochrane and Dr. Paul Brand at the Christian Medical College and Hospital, Vellore, during the course of his treatment, led to the beginning of his interest in leprosy work. The interest was nurtured by Dr. Ramanujam, a well known leprologist in Madras, who introduced him to Prof. Jagadishan, the secretary of the Hind Kushth Nivaran Sangh. He, in turn, put Dr. Desikan in touch with Dr. Sushila Nayar, a close associate of Mahatma Gandhi.

In the early fifties, Dr. Sushila Nayar was the secretary of the Gandhi Smarak Nidhi Kushtha Nivaran Samiti at Wardha, Maharashtra. Through the Samiti, she was trying to carry out leprosy work, in line with Mahatma Gandhi’s constructive work programme. Dr. Sushila Nayar suggested that Dr. Desikan undergo formal training in leprosy work before he joined her in Wardha. He underwent training at the Ackworth Leprosy Hospital, Wadala, Bombay. However, by then, Dr. Sushila Nayar had left Wardha and had become the Health Minister of Delhi State.

Dr. Wardekar, a pathologist, had taken over as the secretary of the Gandhi Smarak Nidhi Kushtha Nivaran Samiti. Dr Desikan joined Dr. Wardekar in 1952. They were joined by a small group of dedicated workers, including a social worker, and assistants. The organization was now christened as the Gandhi Memorial Leprosy Foundation (GMLF). Dr Wardekar had identified 35 villages around Sewagram for a leprosy control initiative. Dr. Desikan visited each of these villages on a regular basis. He walked, cycled, took a bullock cart, travelled horseback and waded across rivulets to reach these villages. He went door-to-door, examining every man, woman and child, in all the 35 villages, for signs of leprosy. This kind of work was exactly what Dr. Desikan had envisaged for himself. Along with his team, he generated awareness about leprosy, carried out surveys and diagnosed leprosy cases among the people there. He successfully motivated patients to attend any one of the clinics he had established in three of these villages, for treatment. Over the next five years, Dr Desikan and his team repeatedly examined more than 30,000 individuals and diagnosed 550 with leprosy. He began to treat patients with Dapsone, a recently introduced drug. This was the world’s very first Survey, Education and Treatment (SET) programme for diagnosis and management of leprosy. The programme paved the way for control of leprosy in India. Dr Desikan showed that the strategy was scientific, pragmatic and a very effective method for control of the disease. The Government of India eventually started the National Leprosy Control Programme (NLCP) in 1955 and the SET method became the standard procedure for leprosy control in the entire country. Later, the program was endorsed by the WHO, and was implemented worldwide.

GMLF had established a Leprosy Control Unit at Chilakalapalle, a semi tribal village in Shrikakulam (presently Vijayanagaram) District, in the Northern part of Andhra Pradesh. Dr Desikan was transferred to the Chilakalapalle Unit in 1957, to strengthen leprosy control work in that area. “Leprosy was rampant there and I was treating nearly 15000 leprosy patients,” recalled Dr Desikan once. Soon, Dr. Desikan found that he was treating patients from beyond the mandated areas covered by the unit. To make his services more accessible, Dr. Desikan provided voluntary services for leprosy control and treatment in many of the tribal villages beyond the purview of the Chilakalapalle unit. Since he was the only doctor in the area, he also organised for medical services for any emergencies in the villages. Although he was immensely satisfied with his work there, he recognized the need to acquire a post graduate degree, and grow in his discipline. He left Chilakalapalle in 1962 for Vellore. At age 36, he enrolled himself for a post graduate degree in Pathology at the Christian Medical College in Vellore, the very institute where he had been treated many years ago. His MD thesis involved autopsy studies in leprosy patients. He finished MD Pathology in 1966.

In 1967, he was selected for the position of a senior research officer at the Central Leprosy Teaching and Research Centre at Chingleput (now Chengalapattu), near Madras. During the course of his tenure there, he undertook a WHO fellowship for a year’s training in academic institutions in the UK, USA and Japan, and honed his skills on mouse footpad experiments and other advances in leprosy research. Back in India, he pioneered studies on mouse footpad experiments to further understand the pathogenesis of the disease.

In 1976, Dr. Karan Singh, the Union Health Minister, asked Dr Desikan to take charge as Director of JALMA, Agra. JALMA (an acronym for the Japanese Leprosy Mission for Asia) was a leprosy institute established by the Japanese. The Government of India, through ICMR, had taken over JALMA at that time. Within a year, the institute began to thrive. Not only did the institute earn a name for outstanding clinical work, but research papers from the institute began to get published in reputed journals. JALMA also hosted many national and international workshops, symposia and conferences on leprosy, and soon found a place on the national and international map.

Dr. Desikan retired from JALMA in 1987 and came back to Sewagram, Wardha, where, with the help of LEPRA, the British Leprosy Relief Association, he set up a leprosy histopathology laboratory in MGIMS, Sewagram. He took charge as the first Chairman of LEPRA India, a post he continued until he stepped down in 2003. LEPRA India was headquartered in Secunderabad. Dr. Desikan steered LEPRA India through many leprosy control activities in Andhra Pradesh and tribal areas of Koraput, Orissa.

Over the years, Dr Desikan received several honours. To name some, he received the ICMR/JALMA Oration Award, the KC Sahu Gold Medal, the Gold Medal of the Argentina Leprosy Foundation, the Certificate of Honour, Medical Research Institute, Florida Institute of Technology.“The best practice of medicine demands just the right blend of humanity and humility”, so wrote Larry Greenbaum. In 2001, he received the Damien-Dutton Award—the highest international recognition for work in leprosy. The director of the Damien-Dutton Society for Leprosy spoke about how Dr Desikan dedicated his life to bring to ‘God’s poorest of the poor’, a sense of self-worth. He admired Dr Desikan for his untiring efforts to provide treatment at the doorsteps of a very large number of patients. Dr. Desikan, however, never let recognition go to his head. His response after he received the award was characteristically Desikanesque: “I feel honoured but I have to remind myself that I am no greater than several others, who have worked, struggled, sacrificed and remained unknown!” He continued to do research from his small office— using back of the envelopes to write his notes—even after he acquired the status of an international hero.

His commitment and firm belief in science was deep rooted. Wary of medical claims unsupported by scientific evidence, and sceptic of myths and anecdotes woven around leprosy, he designed studies that would unravel the mystery of leprosy. These studies might have lacked the methodological rigour which the modern editors demand, and sceptics did question his methods of inquiry and analysis. But no one could deny that these small blemishes notwithstanding, Dr. Desikan generated a wealth of evidence which needs to be acknowledged with the respect that it deserves. His work encompassed the entire spectrum of leprosy: descriptive epidemiology, diagnostics, histology, immunology, physiology, therapy and simple clinical observations. His lifelong interest in understanding the determinants and distribution of leprosy in the nooks and corners of the country is eloquently evident in his publications. He has over 150 publications based on clinical, histopathological and immunological work in leprosy.

In his long and illustrious career, he nurtured the careers of several, helping them reach international heights. In an era of publish or perish syndrome, authorship issues can mar the best of friendships. Dr. Desikan, all through his life, never agreed to put his name to a paper he had not worked on. Nor did he ever gift authorship—he shared just one publication with Dr Prabha Desikan, his daughter, a microbiologist. PubMed search shows that Dr. Desikan was ever willing to give his juniors the pleasure of being the first author of a paper. He teamed up with Ramu, his colleague and dear friend at the Central JALMA Institute for Leprosy, with whom he co-authored 54 articles; with Girdhar he shared 31 publications. Like a true mentor, he rejoiced in the success of his colleagues and juniors.

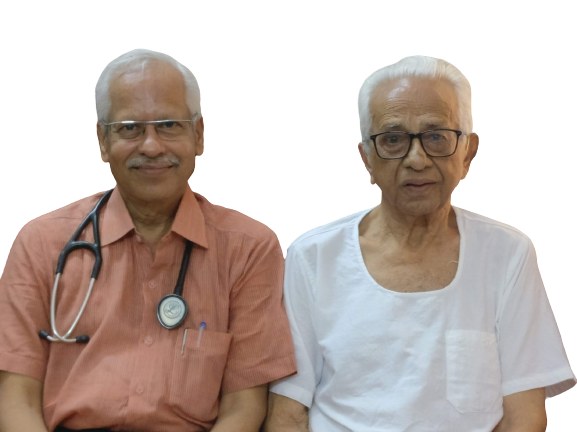

He firmly believed that one must keep one’s knowledge and skills up-to-date throughout one’s working life. Ever eager to take part in educational activities and clinical meetings, Dr. Desikan’s childlike curiosity and quest for learning advances in medicine is very inspiring! A frequent visitor to the Department of Medicine at MGIMS, he dropped in informally on Friday mornings to attend the journal club. And he would be the only one to take notes and ask questions that would often leave the presenter dumbfounded. On several occasions, I discovered that Dr. Desikan’s toughness in science was tempered by grace and wit. He brought compassion and a remarkable sense of humour to everything that he did. His mischievous smile and an amazing ability to pull others legs were legendary.

Dr Desikan loved books and over the decades had acquired thousands of books. In 2006, I borrowed from him a book “A bunch of old letters”—a collection of 368 letters written to Jawaharlal Nehru and some written by him. He was barely able to conceal his tears when he read me a long letter Subhash Chandra Bose had written to Nehru. When I saw him at his home, he would pull out a new book and with a childlike enthusiasm read me the passages from the book. I would go home greatly enriched. He was very particular that the books that he lent ought to be returned. Once I borrowed from him a book, “Great Soul: Gandhi and his struggle with India” by Joseph Lelyveld. A few months later, he wrote me an inland letter—he was ninety two then—politely reminding me to return the book.

Over the last few years, the maladies of old age began to trouble his fragile body and this lifelong wanderer—wanderlust led him to many different parts of the world— was forced to stay indoors. Now that his soul is free, I am sure Dr Desikan must be busy discovering new places—and acquiring new hobbies—in the world he now inhabits.

Desikan sir was most unassuming person, I have ever met. I had more interactions with him in Bhopal, than in Sevagram.

He used to write a diary, and very diligently so. He would also preserve many letters and documents. When I met him in 2014 in Bhopal, he showed me his diary from 2005-06. Seems I was his physician then, and had prescribed him injectable antibiotics. He had documented his illness, tests and injections on that day.

He was still writing his diary, till about a year ago. Quite ambulatory for his age, he had slowly withdrawn to a room in his home in Bhopal.

I would always recall his innocent smile, he would always greet with.

A wonderful tribute! We knew he was a big name in leprosy but for me he was Desikan Uncle – Prabha’s father. A kind person. Uncle and Aunty had invited us for a meal when I was newly married and LP had come for a visit. I remember his saying how little they had spent on their wedding which I always quote to friends – a marriage is about the meeting of two minds whereas the wedding is about the celebration. We last met him when we had come for our reunion. A lovely human being and kind sou

Reading about, Dr Desikan Sir, gives a feeling of how fortunate we were to have these real Heroes as are teachers and mentor. They have spend all their life so happily, peacefully,reaching new heights with simplicity, and grooming life’s of all the students of MGIMS. All the students of MGIMS can say that we are proud to be MGIMS students. Oor teachers at MGIMS has set an exemplary pathways, which may be in our student life we had resented, but had still inculcated the seed in us.

May God, give peace and solace to the departed soul.

Kalantri Sir, I owe a lot to you, not alone for being a great teacher, a healer, but narrating so well about everyone, which we are not aware of. My salute to all my teachers of MGIMS. Whatever I am today it’s all because of them…just I want to be a good person.

I heard about Prof. Desikan during my short stint of almost little over 1 yr as lecturer surgery from 1988 to 1989 when Skand his son-in-law was houseman in Medicine. A real researcher and human being par excellence. My only meeting with Mrs Desikan was when she was probably secretary of KHS. Then I had just joined MGIMS and after almost 1 1/2 months I got married .That time I didn’t have enough money to travel to home to get married and by that time my first salary bill was not prepared. I went and met Mrs Desikan and explained my situation. Immediately she called Gokul ji and made sure I get Rs 1700 as my first salary ,which was enough for me to travel back home to get married.

God bless the departed soul of Prof Desikan with eternal peace and His daughter and Skand the strength to bear this loss.