It was a scorching afternoon on May 4th, 1982, when I first stepped into the medicine ward at MGIMS in Sevagram. Unlike the bustling government medical college in Nagpur where I had trained, this hospital felt serene and peaceful. As I walked in, I noticed a dishevelled resident performing a pleural tap at a patient’s bedside. He wore a stethoscope around his neck—a Littmann stethoscope that never left his neck throughout his life.

He looked at me with a puzzled expression and asked who I was and what I was doing there. Feeling self-conscious under his gaze, I explained that I had been appointed as a senior resident in the Department of Medicine and that I wanted to meet Dr OP Gupta, the department head. A sweet smile spread across his face as he peeled off his gloves, shook my hand, and introduced himself.

“I’m Krishan, but you can call me Kissu,” he said with a grin that radiated both sheepishness and childlike innocence.

I had no idea at the time that meeting Kissu would be the start of a lifelong friendship. Our paths would cross again and again over the years, and we would share innumerable moments of laughter, joy, and even some tears. But in that moment, all I knew was that I had met a warm and friendly soul who would become an important part of my life.

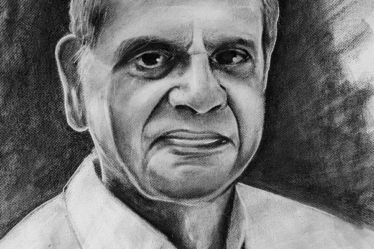

He was Dr Krishan Aggarwal, whom we lost on 17 May 2021.

How was the Medicine department in early 1980? The building, a guest house constructed by Mr GD Birla, was a two-storey structure that had seen better days. As I joined the department on that fateful afternoon of May 1982, I walked down the creaking floors and peeling walls of the ground floor, I could see a few general wards that resembled dormitories, illuminated by dim tube lights.

It was a simpler time, and medical equipment was scarce. The ICU had no mechanical ventilator, no multipara monitor, no infusion pumps, and no central oxygen, suction or air. There was no dialysis machine either. The most coveted investigation was the ECG, and every morning at 8 am, the trio of Dr OP Gupta, AP Jain, and Ulhas Jajoo would arrive at the head of the department chamber to correct the ECG findings that the residents had reported.

Every morning was a race against time as the clock struck 8 am, and the trio of Dr OP Gupta, AP Jain, and Ulhas Jajoo would make their way to the head of the department chamber. It was the most sought-after event of the day, where residents reported their ECG findings for correction. The tension in the room was palpable as the professors scrutinized each finding with eagle-eyed precision, looking for any potential errors or oversights.

“Why hasn’t this resident calculated Estes’ score for diagnosing left ventricular hypertrophy on the ECG?” Dr OP Gupta would ask, with a hint of frustration in his voice. Dr AP Jain would chime in, “And why can’t our residents remember the causes of tall R waves in lead V1?” “The residents still haven’t mastered the vectors and do not know how to calculate the axis,” Dr Ulhas Jajoo would barely conceal his angst. The three medicine consultants would exchange disapproving glances, clearly expecting better from their students.

Dr Gupta couldn’t help but let his administrative side show as well, “The residents seem to be wasting ECG paper. I had sanctioned two rolls a month ago, and they have already exhausted them.” He couldn’t stand such waste in his department. When the administrator in Dr OP Gupta took over, the frustration of wasting ECG paper became all too apparent.

These three physicians were like an unstoppable force, and nothing could deter them from ensuring that every detail was perfect. It was a daily spectacle that the residents had come to dread and respect in equal measure. The ECGs may have been the coveted investigation, but the morning correction sessions with the terrific trio were the true highlight of the day.

But despite the lack of modern amenities, the passion for medicine burned bright in the hearts of the residents and doctors, and they worked diligently to provide the best care they could with what little they had.

The Medicine OPD was nestled atop a hill in the newly built hospital complex. Dr Jain and I would amble up the hill after our rounds, taking in the fresh air and walking past the Sevagram General Store and the Madras Hotel. Once there, we would attend to around 30 to 40 patients over a leisurely three-hour period. The pace of life was slow and tranquil, allowing me to examine each patient and Dr Jain to delve into the psychiatric world of the patient.

In the afternoons, we would gather for our journal club, where we eagerly discussed the latest articles from medical journals. Residents would project them onto the overhead projector and we’d dive deep into the nitty-gritty details. But that was just a warm-up for the Wednesday morning death meeting—an intense academic activity where a resident would present a case of a recently deceased patient. And we did grill them! Every word, every diagnosis, and every decision was scrutinized with fervour by the professors and lecturers in attendance. The tradition continues to this day, 45 years later, in the new building.

To get any diagnostic tests done, a ward attendant had to cycle up the hill to deliver the blood samples to the biochemistry and microbiology labs. And as for X-rays, patients had to be transported in a small ambulance to the radiology department in the new building.

When I first joined, the old hospital building was a bit of a relic, housing only the medicine wards. It was as if we were in a time warp, with its peeling paint, old floors, and tube lights flickering overhead. Meanwhile, the Surgical, Eye, ENT, Orthopaedics, Paediatrics and Ob Gy wards had already moved into the shiny new building down the hill. It wasn’t until 1986, a good five years later, that we finally made the move to the new building ourselves. Finally, all the facilities were under one roof, making it so much easier to see patients, admit them, and test them.

Dr OP Gupta and AP Jain lived just a stone’s throw away from the medical wards in the MLK colony. Dr Gupta was a man who commanded huge respect – he was strict, and he wouldn’t tolerate any slacking off when it came to patient care. Whenever he got bored at home (which was often, considering there was no TV, cell phone, internet, or social media back then), he’d sneak into the wards unannounced, just to make sure everything was running smoothly.

Dr Jain’s Sunday morning rounds were the stuff of legend. He would have all the patient case records meticulously collected and placed on his table, taking pleasure in writing revised case summaries in handwriting he seemed to have developed a fondness for.

Dr Ulhas Jajoo, on the other hand, was a more relaxed presence on the ward. He was known to be friendly and almost a comrade-in-arms to his residents, providing them with a sense of camaraderie and support. He’d start and finish his ward rounds on a Sunday morning like a quickfire spell of T20 cricket. By 6 am, his rounds would be finished, and he’d be off on his scooter to nearby villages to be in the midst of farmers and labourers trying to understand what makes them sick and what they do when they fall sick.