ECG is the first thing that comes to mind when you think of Kiran Munjewar. He met me this morning in the hospital and I seized the opportunity to speak to him.

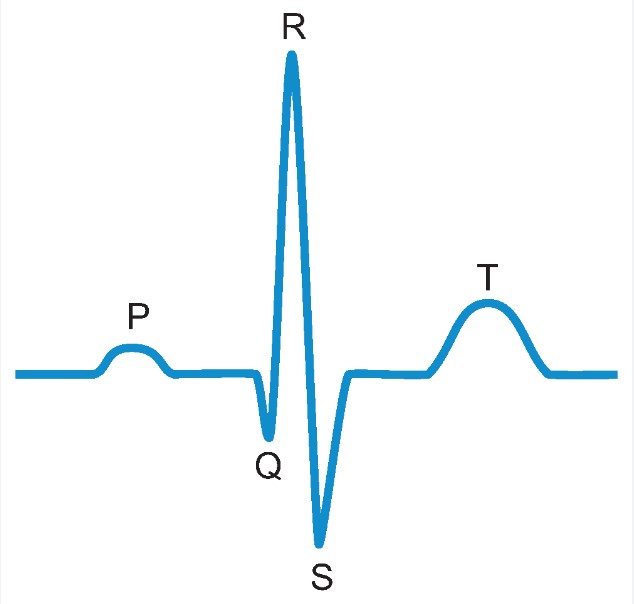

Munjewar was an ECG technician. He is estimated to have recorded close to half a million ECGs in a career that spanned four decades. Little wonder that in his world P waves would flirt with the QRS complexes, leaving the ST segment depressed. Skilled in interpreting ECG abnormalities, he could detect infarcts, arrhythmias and heart blocks with uncanny accuracy. His eyes would quickly scan the 12-lead strip and pick up abnormal rates, rhythm and axis. He would spot the VPCs before they propped up on the monitor. Blocked coronaries bowed before him; he could anticipate arrhythmias before they would arrive. Residents saw him as one who could foretell the future simply by looking at those waves on the ECG strip.

Indeed, during the golden days of Medicine, Munjewar was to Bijwar what Sachin Tendulkar was to Sourav Ganguly. They worked in tandem, calmly, coolly and cohesively. They batted in perfect harmony and could be spotted in the department well beyond the closing hours. For them, the department was an extended home. Without this pair, the Medicine department would not have been what it is today.

Born on 4 July 1950 in Talpade Sutika Grih, a maternity home in Wardha, Kiran was the eldest of four siblings. Vasantrao, his father, owned a farm in Kharangana-Morangna and Vasundhara Bai, his mother, was a homemaker.

Kiran went to a primary school in Kharangana until third grade and then moved to Swavalambi Vidyalaya, Wardha where he completed his matriculation. I also went to the same school, albeit a couple of years later. In the ninth, he migrated to the Arts but his romance with the Arts was short-lived. His Mausi made him go back to science. He spent a month in the local science college, but destiny pulled him to Delhi where he was enrolled in ITI. He obtained a diploma in Industrial Instrument Technician in 1970 and did a couple of jobs in Auto metre limited and Universal electrical in Ballabgarh, when he returned to where his roots were—Wardha.

In 1972, MGIMS— it was just a three-year-old medical school then—wanted to hire an ECG technician and Kiran applied for the post. He was interviewed by Professor Supe who was surprised to know that Kiran failed to recognize him, although Mr Supe was the principal of the Jankidevi Bajaj College of Science where Kiran had spent a month. He was selected and began working in the department of Physiology. Dr ID Singh was the principal of MGIMS in those days and Dr Deshkar was heading the department of Physiology.

Four years slipped by. In 1977, Dr Digmurthy, the Pediatrics head was also heading the Medicine department at MGIMS. Dr SP Nigam was serving as the reader in Medicine. He pulled strings to have Munjewar transferred from Physiology to Medicine. Thus, Munjewar entered Medicine, a department he was to serve until he retired, in July 2008.

“The first ECG machine that I laid my hands on came from Siemens. It was a very heavy machine. Over the years, BPL began to attract physicians – the machine was simple and uncluttered and the Singh brothers in Nagpur provided a prompt and efficient service. Once BPL arrived, it never left the medicine department. In between Dr Khatri, the PGI cardiologist who joined MGIMS on deputation in the late seventies, got a machine from Indore but it didn’t last long,” recalled Munjewar today.

“In the late seventies, the hospital used to conduct a lot of camps in the MGIMS catchment area. Once I went to Sirpur Kagaznagar where I recorded close to 500 ECGs over a week. I Almost single-handedly handled the ECG room where I would record ECGs of the outpatients, those needing pre-op assessments, those coming for annual health checkups and also for residents who were writing ECG-based theses.”

The treadmill arrived in the department in the early eighties and Kiran became an expert treadmill technician—coaxing, cajoling and encouraging the patients to huff and puff on the moving belt of the stress test machine until they completed at least Stage 3 of the Bruce protocol.

On several occasions, Munjewar picked up an acute myocardial infarction in his ECG room, summoned the resident and ensured that the patient received thrombolytic therapy well within the window period. His vigilant eyes must have saved many lives.

Close to fifty times a day, he would perform his daily drill: right arm—left arm—right leg—left leg—chest with amazing speed and perfection. The waves that would dance on the ECG paper would take many shapes— pointed, rounded, running deep, standing tall, occasionally going wide—but the strip would never have vibrations that make the interpretation of ECG so difficult. Recording an ECG, far from being a mundane job, was a religion to him, a belief that would make him produce clean crisp ECGs, patient after patient. A man of few words, he would ensure that his ECG room was uncluttered and there were no loose wires dangling across the bed. His trademark response to small appreciation is vividly entrenched in my memory— just a shy half-smile.

In 1977, young Munjewar found a nidus outside the Medicine department. He formed a credit cooperative society with his friend, Jaipal Yelwatkar (Biochemistry). Soon Mitkar (pharmacist), Surendra Gujar (photographer), and Khodke joined the group. In those days it was difficult to obtain loans from home financing banking institutions. Also, the provident fund deductions were too meagre; the procedure for withdrawing money from one’s own provident fund was too cumbersome.

“Could we find an easy solution that could help the MGIMS staff whenever they needed some money?” Munjewar began to think.

Kiran happened to meet Mr Ballu Joshi (a LIC officer) and Mr Deshpande (Maharashtra Bank) who suggested that the MGIMS staff members can come together and form a Pat Sanstha.

In 1978, Pat Sanstha bought 11 acres of land for Rs 46,000 on Sevagram Wardha road, three kilometres from the MGIMS hostel. “Wasn’t it a bargain price? I did some quick mental maths and asked Munjewar. “No, it wasn’t. The MIDC land was selling at Rs 3600 an acre. We brought it at a considerably higher rate,” he corrected me.

These numbers look so cheap today. The faculty agreed to do a SIP of Rs 100 for buying a plot; the non-teaching staff volunteered to pay half the amount. “Yet, we had great difficulty in convincing the staff to part with their hard-earned money. They thought that either they won’t get the land we were promising or we would run away with the money,” recalled Munjewar.

Over a year or so Drs Narendra Samal (Pathology), Keshav Ingley (Physiology), and CB Taori (Biochemistry) bought a plot in what is now called Dhanwantari Colony. Dr R Narang (Surgery), OP Gupta, AP Jain and Ulhas Jajoo (Medicine), Dr VN Chaturvedi (ENT) and Dr BC Harinath (Biochemistry) followed. Each faculty member got a plot for a princely sum of Rs 500!

In between, Kiran married Usha Tarale—she came from Pimpalkhuta village in Arvi Taluka—in 1982. Chandrakant was born in 1986 and Anuja in 1990. Chandrakant did MBBS from MGIMS (2005 batch), General Surgery (MS) at Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital and obtained MCh (Urology and Kidney Transplant Surgery) at Dr Ram Manohar Lohia Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow. As of now, he is an assistant professor in Urology at AIIMS Nagpur. Anuja obtained B Tech from Shri Sant Gajanan Maharaj College of Engineering Shegaon and following marriage lives in Hyderabad.

Usha, Kiran’s wife, endured several major medical illnesses over the last twenty-five years. Her grit and determination to fight the medical challenges have to be seen to be believed.

Kiran retired from the department in 2008. Following retirement, he served in the ICMR projects and a large randomised controlled trial until 2014.

Kiran now stays at Dhanwantari colony, Warud. Contented with his life, he loves gardening and spends most of his free time tending the garden. “Whether it’s a newly developing flower bud, or watching green tomatoes ripen to red, eyeing a new bird that visited the backyard, or measuring the progress of steadily growing hibiscus; the garden always has something new in store for me every day,” says Munjewar.

“As a new medicine houseman, I would ask him, “ECG theek aahe?”! He was a master,” said Paresh Desai (1980 batch), then a house officer in Medicine and now a paediatrician.

Jyotsna Nigam (1985 batch) did her MD (Medicine) from MGIMS. She says,” He had invited all four of us for dinner before we finally left Sewagram and took my thesis bag as a token of remembrance. We were greatly touched by his gesture.

“Several residents in Medicine did their ECG-based theses with me. He could recall Kapil Gupta (1975), Deepak Telwane (1979), Skand Trivedi, KP Vitthal Rao and Monika Ahuja (1982), Firoz Sogiawala (1983), Sanjeev Batra (1984), Harmeet Singh Dhooria (1989) succinctly.

“Once I had gone to Delhi where I saw Dr Vikram Dutta, the paediatrician at the Lady Hardinge Medical College. Namita, his wife (1989 batch) had done her Ob-Gyn from MGIMS. He treated me with warmth and respect and immediately called Dr Jyotsna Nigam (1985 batch) who happened to be in Delhi at that time. I had worked with Jyotsna’s father as an ECG technician and Jyotsna had also obtained her MD (Medicine) from MGIMS. I can still not forget the love and kindness they showered on me,” Kiran had his throat choked as he recalled the story.

Kiran at 73 is indeed a forgotten gem of the Medicine department. But for the ECGs he recorded, stocked and delivered at the PG activities, the ECG sessions in the Medicine PG activities would have lost their sting. His ECGs would begin animated discussions during the ECG sessions, setting many a resident’s hearts aflutter.

“ECG taught me what life is all about. The elevations and the depressions that I would see on the ECG strips helped me take successes and failures in one’s stride. I learned that the waves on the ECG are symbolic of the ups and downs in life,” said Munjewar as I bid him adieu.

A fitting ode to Munjewar kaka as we know him . It is a matter of pride to understand what MGIMS as we know today was build by the efforts of these humble yet committed individuals.

I believe you are a true “Mujaddid” (an Arabic word for the one who brings renewal in a religion, and comes into being every 100 years) … so you are a Mujaddid for this very great way of life-The MGIMSite!

[email protected]

How succinctly you have written about this unsung hero of our revered department.

In your form, Indian literature lost a gem. What was literature lost was a huge gain for art of medicine. Your skills of making even a mundane thing look artistic and bewitching is unparalleled. All my respect at your feet sir.

Amazing write up sir and equally amazing is your way to make people feel that they matter to you…..😊

I am indebted to Munjewarji – he was the one because of him I was confident in Doing Stress test even during my residency.

Excellently expressed. I could visualise all the sequence of events as if it was yesterday only. He had invited all four of us for dinner before we finally left Sewagram and he took my thesis bag as a token of remembrance.

All fond memories left.

No medicine resident can forget Munjewar and Bijewar.

Very apt description Sir.

Simplicity and perfection were his striking qualities.

Excellent write up for a well deserving person !!

Another wonderful write up Sir.

I remember him fondly.

He was always smiling. Would diagnose ECG abnormalities quickly.

Good to know about his journey.

Great write up about Kiran Munjewar. I have no words to express my thanks the way he energized me during my overnight stay in rural habitats when I was collecting data for my thesis (1982-83). He was quick to perform ECGs in the villages.

Great to hear thank his son is a urologist.

Kindly convey my thanks and good wishes for great health and peaceful future ahead. If possible, I would love to thank him personally.

Sir, as always you have been a stupendous storey teller and writer, reminding verbatim all those moments.

Sir, indeed we all remember him… You have so beautifully penned his life… Words just flow out amazingly from your pen….

What a heart touching tribute to Munjewar ji. We all remember him fondly.

Loved reading it Sir.

He taught me how to use the primitive ECG machine in our old medicine ward. As a fresh Medicine houseman, it was my first house job. He taught me how to prevent the stylus from crazy vibrations, earthing…and so on…. Please say hello to my ECG guru. He might remember me. I also remember the 9am ECG meeting, once a fortnight, I think. It was terrifying for a new houseman…

Munjewarji and Bijewarji, are at two ends of personality spectrum, yet complemented each other in the department. Long back, he also used to do EEG, and that’s where I first met him as a medical student. He zealously introduced me to these waveforms, which I still know nothing about. Then there was this single lead only ECG machine, we would struggle with. At times he would be summoned, to magically fix it and get us a neat long thin strip, with all the waveforms !!!

Excellent write up. I still remember every day I used to sit down with Munjewar to learn how to record a ECG. Indeed a thorough gentleman. Mr. Bijwar and Munjewar were the backbone of medicine department.

Who can forget Kiranji. He was like an encyclopedia for dos/don’ts, the mini lab we operated at the back and helped us get out of trouble every time.